The Diabetic Dilemma

The obligation to thoroughly assess the risk for each patient

by Richard Nagelberg, DDS, and Kimberly Miller, RDH, BSDH, RDHMP

Ongoing global research continues to address the oral systemic connections and their impact on total health and wellness. The consensus in the medical and dental professions is that there is an association between the mouth and the body; however, the strength of the association will be determined by further research — in particular, interventional studies in which periodontal treatment is provided and the effects on systemic events are observed.

Among the various systemic links to gum disease, the strongest is the connection to diabetes. Diabetes is a group of chronic diseases characterized by hyperglycemia (high blood sugar levels) resulting from defects in insulin production, action, or both. It is estimated that diabetes affects approximately 23.6 million people of all ages in the United States. The National Institute of Diabetes 2007 statistics also estimate that about 5.7 million of these people are undiagnosed diabetics. These individuals are totally unaware they are diabetic. This report goes on to say that about 2.6% of those aged 20 to 30 have diabetes while 10.8% of those aged 40 to 59 have diabetes. It was staggering to discover that of those aged 60 and above, 23.8% have diabetes. In other words, one out of every 4.2 patients you see in your dental office over the age of 60 will likely have diabetes.

Mechanism of diabetes

To better understand the mechanism of diabetes it's important to know the primary players, which are carbohydrates and insulin. Insulin is a protein hormone which gets its name from the Latin insula for island, which is appropriate since it is produced by the beta cells in the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Insulin is an essential element in the control of intermediary metabolism, which are the processes within cells that extract energy from nutrient molecules and use that energy to construct cellular components.

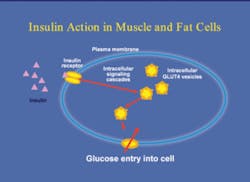

Ingested carbohydrates are broken down in the small intestine into glucose, which is then absorbed into the bloodstream. The elevated glucose in the blood stimulates the release of insulin from the pancreas into the bloodstream. Insulin facilitates the uptake and utilization of glucose in muscle and fat cells throughout the body. All tissues in the body do not require insulin for glucose uptake including the brain and the liver. These tissue types use another, non-insulin dependent glucose transporter.1

There is a receptor for insulin embedded in the cell membrane of the target cells. Insulin binding to the receptor causes activation of the receptor, which then sets off a series of events inside the cell, rapidly culminating in the movement of internal compartments, or vesicles, inside the cell, to another part of the cell membrane. The vesicles contain the glucose transporters which then provide an opening in the cell membrane for the uptake of glucose from the bloodstream into the interior of the cells, (see Figure 1). Insulin also stimulates the liver to store glucose in the form of glycogen and is involved in the importing of proteins into the cells. Any disease or condition that interferes with the movement of glucose into the cells leads to hyperglycemia.

Type I diabetes — Type I diabetes, formerly called juvenile diabetes, is most commonly diagnosed in children and young adults and accounts for 5 to 10% of all diagnosed cases of diabetes. It is characterized by the failure of the pancreas to make insulin. This malfunction is usually caused by auto-immune destruction of the pancreatic beta cells. People with Type I diabetes need several insulin injections per day or an insulin pump to survive. Most people with type I diabetes eventually develop one or more complications including damage to the eyes, nerves, kidneys and blood vessels. Type I diabetics are about ten times more likely to have heart disease than non-diabetics.2

Type II diabetes — Type II diabetes is the most common form and accounts for 90 to 95% of all diagnosed cases. Type II diabetes, formerly called adult onset diabetes, is characterized by insulin resistance in the target cells, in other words the fat and muscle cells do not use insulin properly. Type II diabetes is treated with a combination of dietary modifications, oral medications and insulin injections if necessary.2

Another staggering statistic reported by a recent study suggests that 82% of diabetic patients with severe periodontitis experienced the onset of one or more major cardiovascular, cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular events compared to only 21% of diabetics without periodontitis.3,4 Take just a moment to reflect upon how many patients you see with diabetes and their periodontal condition; you too will feel the magnitude of these statistics. We have an incredible opportunity as clinicians to assist our diabetic patients with their overall health by treating periodontal disease activity early and assertively.

Complications of diabetes

The importance of preventing hyperglycemia cannot be overstated. The effects of elevated blood sugar on the vascular system are the major source of complications in Type I and Type II diabetes. Diabetic complications include retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and cardiovascular diseases. These complications are dramatic and potentially life changing.5

Periodontal disease and diabetes

Diabetic individuals are predisposed to periodontal disease through several mechanisms. Poorly controlled diabetics have diminished salivary flow, leading to xerostomia. The body's ability to kill oral bacteria is considerably diminished as well. Hyperglycemia significantly diminishes the ability of white blood cells, neutrophils in particular, to track, adhere to and kill bacteria.5,6 Additionally, elevated blood sugar leads to elevated glucose levels in the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF). Elevated GCF glucose levels hinder the wound healing capacity of fibroblasts.7

Evidence also indicates that periodontal disease can worsen glycemic control.8,9,10 It is well established that infectious and inflammatory processes increase insulin resistance, leading to hyperglycemia. Periodontal disease has both infectious and inflammatory components.

If research demonstrates that periodontal treatment has a beneficial effect on diabetic control, it would provide evidence for the impact oral health has on general health. Two studies demonstrated significant improvement in blood sugar levels after non-surgical perio treatment. In these studies, nonsurgical treatment was provided for diabetic and non-diabetic perio patients. Both groups of patients showed improvement in their perio condition. The diabetic subjects showed improved blood sugar control 3 and 6 months after perio treatment.11,12 This information should be highly motivating for dental professionals to continue to assertively recommend treatment to all periodontal patients with diabetes.

It is interesting to note that there are only small differences in the subgingival microbiota between diabetic and non-diabetic perio patients,13,14 which suggests that the body's immuno-inflammatory response plays the major role in the increased incidence and severity of gum disease commonly seen in poorly controlled diabetic individuals.3

The dental professional's role

It is clear at this point that maintaining good oral health and controlling existing periodontal diseases has implications far beyond the oral cavity. Optimal oral health is only possible if dental providers and patients do their respective parts.

A few suggestions to improve your clinical protocols involving the treatment of diabetic patients follow:

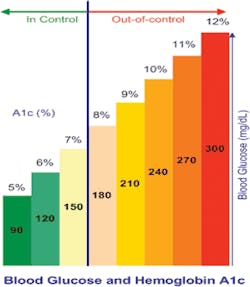

• Ask all patients with diabetes for the results of their last HbA1c test and consider the HbA1c score when treatment planning.

"This blood test measures the percent of glucose that is attached to red blood cells. This test gives an accurate indication of how well diabetes has been managed over the preceding 2-3 months. The HbA1c level is the primary parameter physicians use to monitor blood sugar control for their diabetic patients. Well controlled diabetics have an HbA1c of 5-7%. Readings of 8% and above indicate poor glycemic control. Well controlled diabetics have the same risk of developing periodontal disease as non-diabetic individuals. Poorly controlled diabetics have a much greater risk of several complications including periodontal disease. Periodontal treatment outcomes for well controlled diabetic patients will be the same as non-diabetics. Poor glycemic control contributes to less predictable treatment results, and may factor into the type of periodontal therapy undertaken."

• Visit www.perioeducation.com and click on the Research Plus link to access the "Defeat Diabetes Screening Test" from PerioFrogz.

• Use the Diabetes Screening Test for:

- Every new patient with a family history of diabetes

- Annually for all patients over the age of 60

- All existing patients during health history and risk assessment updates and thereafter every 5 years unless over the age of 60

• Obtain a color copy of the HbA1c graph for use as a visual aid in each operatory. Print your copy by downloading from www.perioeducation.com. Click on the Research Plus link to access the HbA1c graph from PerioFrogz. Once you have printed the graph, laminate and keep one in each operatory.

With the current understanding of the relationship between periodontal diseases and overall health and wellness, as dental professionals we are obligated to educate our diabetic patients on the importance of good oral health. It is no longer optional for us to provide in depth risk assessment, including questions about diabetes. According to the AAP, "Risk assessment goes beyond the identification of the existence of disease and its severity, and considers factors that may influence future progression of disease. Identifying adverse changes in risk factors, which might be suggestive of disease onset or progression, is an important clinical concept."15

As ongoing research continues to address the oral systemic connections and their impact on total health and wellness, the consensus in the medical and dental professions is that there is an association and in our opinion, this association should be addressed with every patient who could be impacted by this information. While interventional studies and ongoing research continue to expand our knowledge, we must recognize our obligation to our patients and do our part now. For every patient under our care, everyday, we must make the effort to thoroughly assess their risk factors and incorporate that data into our comprehensive treatment recommendations.

About the Authors

Dr. Richard Nagelberg has been practicing general dentistry in suburban Philadelphia for more than 26 years. He has international practice experience, having provided dental services in Thailand, Cambodia, and Canada. Dr. Nagelberg has served on many boards and advisory panels and is currently a member of the Georgetown University Board of Governors and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society Advisory Panel. He is a co-founder of PerioFrogz, an information services company, and is on the speaker's bureau of OraPharma and the Seattle Study Club. Kim Miller, RDH, BSDH, RDHMP is a partner of the JP Institute and a founder of PerioFrogz. As a graduate from Loma Linda University in 1981 she received a bachelor's degree in dental hygiene. In addition to clinical practice, Kim has been a consultant and trainer with the JP Institute since 1992, coaching more than 500 practices teaching a hands-on curriculum.

References:

1 Physiologic Effects of Insulin, p.2 2007 Nov, R. Bowen, Colorado State University

2 National Institute of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, NIH News June 5, 2004

3 Measley BL, Oates TW. Periodontal Inflammation and Diabetes Mellitus. J Periodontol 2006 Aug;77(8):1289-1303.

4 Thorstensson H, et al. J Clin Periodontol 1996;23:194-202.

5 Fowler MJ. Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes. Clinical Diabetes. 2008;26(2):77-82

6 Manuchehf-Pour M, et al. Comparison of neutrophil chemotactic response in diabetic patients with mild and severe periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1981;52:410-415.

7 McMullen JA, et al. Neutrophil chemotaxis in individuals with advanced periodontal disease and a genetic predisposition to diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1981;52:167-173.

8 Nishimura F, et al. Periodontal disease as a complication of diabetes mellitus. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:20-29.

9 Sammalkorpi K. Glucose intolerance in acute infections. J Intern Med. 1989;225:15-19.

10 Yki-Jarvinen H. et al. Severity, duration and mechanism of insulin resistance during acute infections. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1989;69:317-323.

11 Navarro-Sanchez AB et al. J Clin Perio. 2007 Oct;34(10): 835-43.

12 Faria-Almeida R, et al. J Periodontol. 2006 Apr;77(4):591-

13 Zambon JJ, et al. Microbiological and immunological studies of adult periodontitis in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1988;59:23-31.

14 Sastrowijoto SH, et al. Periodontal condition and microbiology of health and diseased periodontal pockets in Type I diabetes mellitus. Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:316-322.

15 American Academy of Periodontology statement on risk assessment. J Periodontol. 2008 Feb;79(2):202.