Care process improvement

by Cindy Quinn, RDH, BS

Dr. Teknol has just announced that the office is going green, doing away with paper. They are joining the federal initiative to implement electronic health records (EHRs). Cathy, the hygienist, has dreamt of this moment and appears noticeably thrilled at the decision, so the dentist asks her to develop an action plan by the next staff meeting. The rest of the staff is in shock. They begin nervously chatting about the minutiae involved in running a practice. While it is normal to look at dentistry as “rules, roles, and rooms,” the real emphasis lies in optimal patient care, which is the purpose of EHRs.

When going paperless, it is more productive to focus on care process improvement by thinking about the tasks involved in dental care, rather than rules, roles, and rooms. Most people are not used to thinking about what they do every day in terms of tasks, processes, and workflows. Simply put, the tasks make up the process of care and can be either physical or mental. What one brings to a task, also known as the input, is as important as the outcome or output of that task.

Essentially, every dental office does the same thing. They seat patients, evaluate their health and needs, orchestrate treatment (care) planning, sometimes deliver that care, and dismiss patients until their next appointment. This uses procedural knowledge. Every provider is also a decision-maker, to one extent or another, when evaluating patient symptoms and data against clinical practice guidelines. This requires tacit knowledge. Finally, every provider considers him- or herself an ethical breadwinner, bringing home the fruits of their labors after providing the best quality of care. Dental treatment is viewed as production. But what about the cost savings behind improving the care process, those associated with higher efficiency and effectiveness? That requires declarative knowledge, and many offices have not developed methods to measure these variables.

The care process

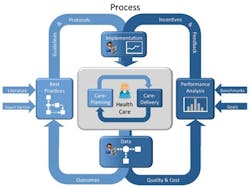

To set the framework for discussion, a review of Reward Health Sciences’ Care Process Improvement diagram is in order (See diagram above). Dr. Richard E. Ward, a physician with an MBA, has conceptualized care management and clinical practice improvement on the macroscopic level. Generally speaking, there is a process for care planning and a different process for care delivery. Care planning requires that the provider determine if any intervention is necessary for a problem — for example, whether or not an antibiotic should be prescribed. The underlying tenet is that every provider wants to do the right thing when choosing the best alternative for treating the problem. In contrast, the process for care delivery requires execution of the plan without wasting resources or making a mistake. These two processes form a cycle for all decisions and subsequent decisions as the patient receives treatment. What is the input? What does the provider bring to the task involved in treatment? Data — data on the patient’s current health, data on procedures that have been scientifically demonstrated as safe and effective, and data on past experiences in a similar situation. What does the provider get from a task? Outcomes. When viewed from the macroscopic health-care perspective, this process dictates the functional status, quality of life, and satisfaction that are experienced by the population. That is the reason that the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) focuses on “core measures,” and mandates both the accurate measurement and reporting of outcomes. This builds principles of best practice, intended to support the decisions of clinicians rather than replace critical thinking and judgment.

Of course, the other use for data is in objectively evaluating performance. The quality of one’s performance, or the performance of material used in the task, should be measured frequently with reports. The old adage “You can’t improve what you don’t measure” rings true. Reports are not useful unless they are used to modify clinical practice. For example, a hygienist has a choice to place resolution material in a pocket, motivate the patient to shorten the recall interval because of the pocket, or suggest that the dentist make a periodontal referral. Making a decision about which will serve the patient best, with respect to the quality and lifespan of treatment in the area, requires an analysis of its performance such as:

- Which procedure works optimally in this situation?

- Can I perform the procedure under optimal conditions?

- Does the procedure generate reasonable performance revenue for the time involved?

The typical practice management system (PMS) cannot offer guidance. These systems have been instrumental in improving the business functions of dentistry, and few want to backtrack to the manual processes used years ago. The PMS software enables providers to streamline administrative processes and store data on the computer. But now is the time to modify clinical practice to incorporate electronic health records, thus extending the use of stored data and increasing the efficient coordination of care between multidisciplinary health-care practices. If the office has a practice management system, one should encourage the vendor to integrate it with electronic health record (EHR) software. The former handles administrative functions so one need not handle as much paper, read handwriting, or perform repetitive tasks by hand. The latter is a secure and searchable “Rolodex” with patient files, their pharmacies, standard usage codes that are tracked, online scientific literature to support clinical decisions, and one-click connections to a patient’s specialist. EHRs focus on streamlining the office workflow and improving patient safety.

While it is difficult to accurately reflect the monetary savings of electronic health records in this emerging industry, a Rand Review from Spring 2009 that combines hospital and physician office activities actually projects that the net cumulative efficiency savings would be five times greater than the EHR adoption costs, 15 years out. The study indicated an expected $142 billion in efficiency savings for physician offices and a $371 billion savings for hospitals over time, but those gains will not begin to be realized during the first three years.

Linking PMS with EHRs for care process improvement

Historically, dental practices have been unable to automate the collection and secure sharing of clinical findings and data. Yet, it is quickly becoming a mainstream reality in medicine, through health information technology. Backed by government incentives, the adoption of electronic health records enables automatic tracking tools to improve process management. Tracking allows an office to set benchmarks for improvement, whether they pertain to patient care or procedures. As part of ARRA, the Health and Human Services’ Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology has funded 62 Regional Extension Centers around the country, which stand ready to assist practices that plan to implement EHRs. Dentists are listed as eligible professionals but they must see a high percentage of unserved and underserved patients, especially children. Many are unaware. Already developed, the Department of Veterans Affairs VistA software is one example of integrated medical and dental information. Screenshots of their VistA patient record system are shown on the previous page. Passage of the ONC HITECH Act also generated funds to train mid-career professionals, with backgrounds in health care or IT, to facilitate the implementation of EHRs. These professionals are referred to as “clinical informaticists,” as a broad label for this emerging field.

Change invades

The best method for making a dental team nervous is that six-letter word at 8 a.m. on Monday — CHANGE. Worse yet? Unplanned change. Many consider existing, dysfunctional chaos better than unplanned change. Think back to the banking industry and the evolution to the ATM that most use today. Had banks put a box out front on some Monday at 8 a.m., few would have tried it. Instead, they secured adoption with a well-thought-out action plan that focused on charging for teller transactions while the free, well-lit box offered 24/7 convenience and no lines. Their action plan looked at the horizon — how to make money convenient to move and use while instilling a feeling of security. At the same time, they reduced overhead.

When Dr. Teknol goes green, he must also have an action plan. Bottom line, many changes to the process of paper flow during patient care really manifest as a change in workflow. Note that the changes to workflow might also affect the location where a task is performed, the perspective of one’s information needs at a given moment, or both. The flow of patients entering the office and getting their needs met are equally as important as the flow of patient information within the practice, whether patients are present or not. Essentially, a redesigned workflow normally streamlines these processes. There will be no need for searching through 10-page charts, waiting for forwarded dental records, starting over to replace an illegible periodontal chart, or remembering whether the patient prefers fluoride foam or varnish. In-office messaging and task assigning, with a click, will minimize interruptions and save the time associated with finding a team member. There is a handy AHRQ Workflow Assessment for Health IT toolkit cited as a tool at the end.

Dr. Teknol contacts some EHR vendors to determine how they help handle the change in procedures, aside from installation, training providers, and supporting the actual EHR that makes the office green. They coordinate their product with a project manager, workflow analyst, and trainer to help practices have a successful go-live experience. These professionals, trained through the provisions of the HITECH Act, close the gaps between IT and specific workflow procedural changes. The vendors’ products have many features designed to automate, consolidate, and track, freeing up both staff and providers from repetitive tasks and rework. Dr. Teknol and Cathy research available products and establish a budget and timeline.

Spring into action plan

Cathy develops the viable action plan. First, she assesses the office culture and the team members’ readiness for change. She draws up a charter, the specific details about the transition, to seek valuable input from the rest of the team. She knows that ground rules must be in place (See sidebar, “Ground rules: optimizing input”) prior to team collaboration. When every employee in the office is part of the idea generation, they are also more responsive to participating in the solutions. Second, the entire office maps out the current practice workflow as a flowchart and creates a list of common processes. Once the process steps are fully identified, the office can drill down through the tasks to identify overlapping roles and inefficiencies.

Here is a sample of their work for dental hygiene:

Third, the team discusses the changes that will occur during the transition. Which processes will need to be revised? Which will disappear? Perhaps it is necessary to resequence tasks. Fourth, Dr. Teknol writes up and presents his vision for the integration of electronic health records into the workflow, and presents his written timeline for implementation. Fifth, a project team is formed and members sign up for responsibilities. Sixth, the group discusses ideas to improve efficiency and creates a revised document with a revised flowchart, which is reviewed by the HITECH professionals. Everyone is reminded that changes required when going green, or adopting electronic health records, will definitely change the workflow of the practice, and that requires care analysis to avoid gaps and miscommunication.

Everyone is focused on the horizon.

What’s in it for me?

Hospital systems, physicians, rural clinics, and federally qualified health centers currently have the spotlight. Initiatives have focused on health disparities as well. The backbone question is, “What’s in it for them, besides monetary incentives?” The answer lies in the coordination of data from many sources and increased efficiencies that will improve the quality of care and decrease their liabilities. Since dentists are listed as eligible providers, they will probably be expected to implement EHRs, even though they have not been the focus of the government initiatives or the media. Many have probably heard of the difficulties and costs associated with poorly planned transitioning and remain apprehensive. Nevertheless, when studying the successful transitions, it is clear that there are significant advantages for dental practices — a lot of them. Think back to the efficiency of the current inputs and outputs of specific processes in the office. Is there potential for working smarter? Recall the Rand Review. Is there potential to save money?

First and foremost, increased patient safety is pivotal. Information technology provides automated alerts for drug-drug interactions, allergies, and chronic conditions that may affect treatment. It also tracks conditions over time, with trend graphs. Technology reminds the user of pending treatment, referrals, or the need for an updated full series. It catches inconsistencies that may lead to error, and flags potentially redundant procedures. Technology, through electronic prescribing, will alert a dentist that a patient has received painkillers from seven other providers in a month — a somewhat different type of patient safety.

The second consideration is the increased clinical efficiency, highlighted earlier. When workflows are streamlined by information technology, there are fewer steps to completion or action. Tasks requiring less training are transferred from higher-trained team members who are accountable for treatment. Hand-offs are seamless because quick-text or click-selected entries are made while the patient is still seated, and viewed immediately on other screens in the office. Similarly, an authorized provider can view standardized triage forms and updated health histories securely, from any operatory, shortly after the patient is seated. Perhaps the gold nugget of information technology lies in the ability to make real-time decisions about patient care without the liability of limited information or data. All documents received, stored, and processed are located on one device that, with a click, is searchable. Patient Jones will be able to grant access to her health records, via computer, and a dental professional will readily see that her “pink pill twice a day” has relevance to pending care. And if they do not know the answer, a couple of clicks will lead providers to clinical decision support for the situation. Better efficiency frees up providers, such as Cathy, to focus on the hands-on, chairside care needed during each appointment. It removes the risk of lost files and forms, and calls attention to items that are amiss. Going green not only helps the environment, but it will also help Cathy practice to her full potential without redundancies or inadvertent omissions that are common in a busy schedule. Others may be green with envy!

As a corollary to clinical efficiency, information technology also automates some administrative tasks so team members can spend more time on patient-related care. If patients choose to schedule or reschedule appointments online, they will receive email reminders of their appointments and prompts to update their medical histories in advance, thereby reducing needless delays for providers. Arriving patients will have their insurance eligibility auto-checked, with charges captured upon documentation sign-off. These will be automatically submitted for payment. Technology also enables coordination. The dental lab can post the status of a case or questions that have surfaced, or a periodontist can inquire about prior periodontal documentation for a patient who has been referred for consultation. Practices with multiple locations can coordinate their activities and resources, without frequent interruption.

Third, information technology facilitates the effectiveness of care. The synergy created when medical care providers and dental practitioners integrate their training to monitor disease is the optimum use of talent. It puts patients in a better position to understand the systemic link between some conditions. This totality of care facilitates the proper sequencing of health-care activities too. Should a patient have a toothache while traveling, the dentist handling the emergency could have electronic transmission of recent treatment records and images sent quickly, with a click.

For care to be effective, health-care providers need interoperability, the ability to “understand” others’ data. The agreement on terminology standards and numeric coding, often categorized as part of Health Information Exchange, have been proposed and will be presented in another article.

What should other hygienists do to encourage the adoption of electronic health records? They should first learn more about EHRs, perhaps volunteering at a health clinic to see the paperless concept in practice. Hygienists should begin to follow this topic with an eye toward care process improvement, and generate pull-through of the idea to employers who have not explored the benefits. With a decision to proceed, their contributions to an action plan should keep team members focused on the horizon to embrace change. They should insist on professionally trained facilitators to transition workflow redesign and implementation so their office experiences little disruption and does not jeopardize data.

The greatest impetus for change rests in saving both time and money. Of course, offices may be skeptical unless a proponent is in their midst. Proactive hygienists will recognize the contribution that health information exchange has for improved patient care, and will facilitate change. Perhaps it is easier to consider the transition to electronic health records when one estimates their return on investment with a calculation tool at www.microwize.com. It is geared toward physicians but is easily modified for dental practices, allowing a tailored analysis for the structure of their facility. An experimental example of a facility with one dentist and one hygienist, in a private practice, estimates ROI of $38,153 after a year of EHR use. Some of the savings stem from workforce automation and reduction in manual input, a result of care process analysis and workflow adjustments that eliminate redundant activities and provide faster access to clinical decision support information. Some savings result from outcomes analysis when an office can track their protocols, performance, and resource allocation and make adjustments. Output like referrals and prescriptions will not even be touched by human hands.

The computer cannot replace the expertise that dental professionals have accumulated, but it can replace the paper they have accumulated. It assists memories, organizes data, and stores it for easy retrieval. Essentially, it is just a bigger version of the hand-held devices that have emerged to make personal lives more efficient. The time is ripe to jump on the government bandwagon to make dental practices more efficient, enable them to measure the effectiveness of treatment, and safely treat patients with chronic conditions that warrant interaction with the medical community. Each of these dental practices will have become the dental Mecca on Main Street.

Cindy Quinn is the first-year clinic coordinator at a new dental hygiene program in Mesa, Ariz. Those with an interest in starting a Community of Interest as a “dental hygiene Somebody” should email her at [email protected].

Special thanks to Terry G. O’Toole, DDS, and Richard E. Ward, MD, MBA.

References

Barlow S et al. The economic effect of implementing an EMR in an outpatient clinical setting. Journal of Healthcare Information Management. 18(1)46-51.

Health Information Management Security and Services Association, www.himss.org.

Rand Review “Health Information Technology Savings Dwarf Costs Over the First Fifteen Years, then Keep Growing.” Centerpiece Sept. 2009. www.rand.org/publications/randreview/issues/Spring2009/cpiece.html.

Ward RE. “Approach: Care Process Improvement.” http://rewardhealth.com/approach-to-care-process-improvement.

Suggested tools

AHRQ Workflow Assessment Checklist —

http://images.ahrq.gov/imageserver/ahrq/withittoolkit/files/Checklist/Workflow_Assessment_Checklist.pdf

Electronic Medical Records Checklist —http://images.ahrq.gov/imageserver/ahrq/withittoolkit/files/Checklist/Electronic_medical_record_checklist.pdf

Workflow Assessment for Health IT Toolkit —

http://healthit.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/health_it_tools_and_resources/919/workflow_assessment_for_health_it_toolkit/27865

www.microwize.com/emr_roi.htm

www.workflow.com

Ground rules: optimizing input

- Present your position clearly, then list the reactions, and consider them carefully.

- Look for acceptable alternatives when at a stalemate.

- Never change your mind just to avoid conflict.

- Discuss until you reach consensus, and avoid voting or bargaining.

- Seek out differences of opinion because disagreement generates a wider range of information and opinion, which often improves the decision.

Common Process Steps Related Task (examples)

Appointment scheduled Confirming patient

Set up treatment room Appropriate tray setup

New patient intake, or Patient demographics

Existing patient intake Evaluate deposits

Patient assessment with diagnostics Radiographs

Treatment planning Charting

Patient education Flossing instructions

Prophylaxis or disease management Debridement

Dentist’s exam Oral cancer exam

Close out documentation with billing codes

Past RDH Issues