BY NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD

Treating animals in the zoo environment is always fascinating. Few individuals, though, enter this domain and stick with it as long as Dr. John Scheels has. I met John in Milwaukee, Wis., a few years ago when he asked me to present a program on oral lichen planus for The Milwaukee Dental Forum Group. This is where I learned about the detailed work that John performs for the Milwaukee County Zoo as their "dentist on call." John has been providing this service for over 30 years.

---------------------------

Other articles by Burkhart

---------------------------

He also provides educational lectures for those learning to become a veterinary dentist, a veterinarian, and on the subject of animals in captivity. He has conducted continuing education programs on the subject of zoo dentistry for the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. During a recent interview, I asked John some specific questions about his passion for treating animals in captivity.

How did you get involved in treating animals at the zoo?

I read an article in a dental professional publication describing a dentist' experiences treating animals at a zoo in another state. I kept the article for a few weeks and then took the chance to call Milwaukee County Zoo, asking whether they had the need for a dentist to work with their veterinarian. Dr. Bruce Beehler had just been hired a couple months before as the zoo's first full-time veterinarian. Dr. Beehler had recently completed a zoo residency at the national zoo in Washington D.C. He had worked with a dental consultant there and so welcomed my interest.

One of the zoo's two young orangutans had recently fallen and injured its hand and lower incisors. Dr. Beehler and primate zookeeper, Sam LaMalfa, allowed me to examine "Trick" while Sam held him. A couple days later, I raided my dental office for a basic dental instrument setup and some spare extraction instruments. Dr. Beehler sedated Trick, and I extracted two severely damaged incisors using a flashlight. And so our zoo dental kit and practice was inaugurated!

How do you become a veterinarian dentist or a zoo dentist?

Zoo veterinarians treat hundreds of species of animals. Their patients include fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals, ranging from pygmy marmosets that weigh less than a half-pound to elephants that weigh tons! Since the 1980s, sophisticated, collaborative record keeping and their professional organization, the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV) has elevated the level of care they provide.

Human dentists and medical doctors are among the consultants that zoo veterinarians commonly call on for assistance, especially for primates. For example we have cardiologists and an ultrasonographer that have monitored and guided treatment for chronic hypertension and cardiac disease in our apes for almost 20 years. They have published multiple scientific papers about their efforts, contributing to care for all captive apes.

As a zoo dentist, I have treated over 90 species. Since the 1980s, veterinary dentistry for pets and horses has evolved from only tooth extractions to comprehensive care and become a boarded specialty. I was invited to develop a curriculum for an elective dentistry course at the University of Wisconsin's school of veterinary medicine in 1986. We eventually provided CE courses for practicing veterinarians, and the course become a regular curriculum course. Currently, two full-time, boarded veterinary dentists manage the courses, dental clinic, and a residency program. The American Veterinary Dental Society has developed into a comprehensive organization, with a quarterly refereed journal and outstanding website resource. I reviewed for the AVDS journal for 15 years.

What are some of the challenges in veterinary dentistry and treating the variety of animals that are found in zoos?

The initial challenge of treating animals is dealing with a patient that cannot describe their symptoms and must be treated under general anesthesia. In fact, they often make efforts to hide their pathosis, as a sign of weakness.

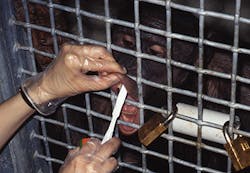

At Milwaukee County Zoo, we periodically hold continuing education seminars for the zookeepers to illustrate and discuss signs of pathosis, including dental disease. These include obviously fractured or mobile teeth, not eating normally, dropping food, swelling on the face or jaws, chronic drainage tracts, drooling and blood in the saliva (see Figure 1). Unusual chewing motions or head posture might indicate difficulties when chewing and pain. Our observant zookeepers are our first line of health care much as family members are for each other!

Figure 1

With the difficulty in observing problems in these animals, what are some of the disease states that may parallel those of humans?

The types of pathosis that we encounter in zoo animals are parallel with those of humans. Of course, their mouths and teeth range widely in size, shape, and physiologically. The enamel, dentin and cementum are the same, but often in different anatomical arrangements.

Periodontal disease is still the main reason that animals loose teeth. This is especially true for pets and zoo animals that live multiple times longer than their wild counterparts. Chronic periodontal disease is a systemic burden for animals as it is for humans. Dental prophylaxis has very limited effectiveness for zoo animals because daily hygiene is essentially impossible, with very rare exceptions. Therefore, proper diet, providing optimal nutrition and texture as close to natural, is a constant goal (see Figure 2).

The most common treatment we perform is still tooth extraction. However, we often perform endodontic therapy to save anatomically critical teeth, such as canines in carnivores (see Figure 3). We have learned to deal with both dimensional and microscopic anatomical challenges in various animal groups to achieve endodontic success. We have also learned how to resolve serious jaw infections such as "lumpy jaw" in herbivores.

Figure 2

The parallels of human and veterinary medicine are very clear. That is why knowledge of animal health and disease can contribute to human healthcare knowledge. For example, I first learned of MTA (mineral trioxide aggregate) use in endodontics in a veterinary publication. Veterinarians are increasingly contributing to human medicine as we have learned that zoonoses (disease shared by humans and animal species, especially primates and birds) are much more common that previously understood!

Figure 3

What do you believe are some important facts that we learn from the observations of these animals?

Knowledge of animals' natural history is very helpful in understanding their dental health condition. The herbivores illustrate many types of dental physical and physiological specializations to manage their fibrous diets. For example, rhinoceros and equine teeth erupt constantly throughout life, their teeth having a finite length. A rodent's incisors grow constantly throughout life, having open germinal root apices. Elephants, kangaroos, manatees, and warthogs are species that have mesially migrating molars to compensate for tooth attrition.

These are examples of dental physiologies must be considered when planning treatment.

Zoo animals are treated while under general anesthesia and examination, diagnosis and treatment must be done efficiently and effectively. There are very limited opportunities for frequent follow up. Therefore, thorough preparation for each species is very important.

With all that we can learn from the animal population, how do zoos plan to expand their activities and sustain their existence?

Zoos are justified primarily by their educational value to our understanding that animals and their natural habitat's condition are critical for the earth's, and our own health. If we hold wild animals captive they deserve to be provided healthy, comfortable lives. It is a privilege to contribute to their health care.

There are very limited opportunities for dentists and hygienists to get involved, compared to 20 years ago because of development of the veterinary dentistry subspecialty. However, there are not enough veterinary specialists to cover all animal facilities. Offering to be of assistance to a veterinarian may be welcomed in either a private or zoo practice.

The principles of periodontal disease are universal in all mammal species, so hygienists can contribute to diagnosis and treatment. They are simply presented in a different package! And with all the resources of the Internet, especially the American Veterinary Dental Society website archives, one can access the current level of veterinary dentistry knowledge.

Conclusion

The interview with Dr. Scheels was fascinating. I learned a lot about his passion in treating these animals. I also learned that there is some key parallels that animals have with humans and the understanding of these connections is so important. One of the most interesting comments that Dr. Scheels made was the psychological component of the animals that try to hide a disease or illness, because the illness or disease may make them appear weaker. We sometimes will see this in humans as well who do not readily admit that they may need some assistance.

If anyone were considering the field of veterinary dentistry, Dr. Scheels would be an excellent person to speak with because his passion for this work is immediately evident and he loves to speak about the subject.

As always, thoroughly observe and listen to your patients. And always ask good questions! RDH

NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics, Baylor College of Dentistry and the Texas A & M Health Science Center, Dallas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (http://bcdwp.web.tamhsc.edu/iolpdallas/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. She was a 2006 Crest/ADHA award winner. She is a 2012 Mentor of Distinction through Philips Oral Healthcare and PennWell Corp. Her website for seminars on mucosal diseases, oral cancer, and oral pathology topics is www.nancywburkhart.com.