BY NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD

Etiology: The fissured tongue, noted by its deep furrows and fissures, is not uncommon in the general population and may appear in varying stages of fissuring at any given time. Both genetics (congenital anomaly) and environmental factors have been cited for its occurrence. However, the etiology is still uncertain and debated.

A link with systemic diseases and also with geographic tongue has been implicated. A study by Picciani et al., 2015, concluded that, out of 348 Brazilian patients ages 18-90, higher percentages of both geographic tongue (GT) and fissured tongue (FT) were found in psoriatic patients than in the general population. Data also indicated that GT occurred more frequently in early-onset psoriasis, and FT occurred more frequently in late-stage psoriasis.

-------------------------------------------------------

Other articles by Burkhart

- Tonsilloliths: Opacities on panoramic images

- The elusive enamel pearl

- Oral Pemphigus and Pemphigoid: Why are these conditions so hard to diagnose?

-------------------------------------------------------

Additional considerations that may increase oral inflammation in general are flavoring agents such as cinnamon. It is known that flavoring agents may cause hypersensitivity reactions (Endo and Rees, 2007). Chewing gum, candies, breath mints, and certain highly flavored toothpastes may also cause problems for the patient with hyperkeratosis and sensitivity reactions. One study (Jarvinen et al., 2014) suggests that large papillae in the fissures cause inflammation and edema to occur. Hypothyroidism may be a consideration since the tongue may be enlarged with this condition and the tongue may not have the oral space needed, thereby folding over on itself and contributing to fissures.

See sidebar for conditions that may be associated with a fissured tongue.

Certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, heart medications, and anti-anxiety agents) may cause xerostomia. Many types of medications, both established and newly developed, as well as combinations, have been known to contribute to xerostomia. The dryness may contribute to fissures.

Epidemiology: Fissured tongue is not common in children but has been reported to increase with age in adults. Studies (Pedersen et al., 2015) reported results from a group of 668 Danish individuals aged 65 to 95 years old, and 9.1% of this population was diagnosed with fissured tongue. The authors attributed the percentage to a female predilection, xerostomia, and low-unstimulated whole and labial salivary secretion. Other sources cite a population of up to 5% as being affected with FT, and others report a male predilection.

Pathogenesis: Fissuring of the tongue may be associated with several conditions as mentioned above, but the papillae of the tongue vary. Some tongues have large, swollen papillae that vary in size, smoothness, and the types of papillae most affected. Pedersen found that atrophy of tongue papillae is a clinical indicator of medication-induced xerostomia. The tongue may be affected in multiple areas, but most commonly on the dorsal surface with propensity toward the centerline.

Conditions Associated with a Fissured Tongue

- Psoriasis

- Orofacial granulomatosis

- Pernicious anemia

- Nutritional deficiencies

- Low serum levels of vitamin A

- Down syndrome

- Diabetes mellitus

- Autoimmune disease states

- Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (MRS)

- Geographic tongue association

- Acromegaly

- Sjogren's syndrome (due to decreased salivation)

- Certain medications taken for various disease states

Differential Diagnosis Considerations

- Inflammatory reactive lesions (hypersensitivity reactions)

- Infections

- Premalignant lesions and neoplasms

- Syndromes and familial conditions

Cited source: Binmadi et al. 2010

Clinical Suggestions for a Fissured Tongue

- Evaluate for any systemic disease states that are associated with tongue fissuring.

- Evaluate patient for xerostomia (certain medications and conditions may cause dryness).

- Recommend a soft-bristle brush to clean tongue (suggest a child's toothbrush since the head is smaller, bristles are softer, and they will flex to reach the crevices.

- Replace the toothbrush if there is an illness, virus, or candida. Toothbrushes can also be cleaned every few days with hydrogen peroxide by just pouring liquid over the brush head, followed by hot water rinsing of the brush.

- Regular use of a tongue cleaner. Educate the patient on use of the device.

- Advise patient to rinse with water frequently. Drinking pure water cleanses the tongue and oral tissues. Water also hydrates all systems of the body.

- Check periodically for signs of candida. Often burning is a sign of candida along with white/yellow coating on the tongue surface.

- Antimicrobial mouth rinse may be suggested. An alcohol-free rinse is recommended.

- Discontinue flavoring agents such as wintergreen, peppermint, and cinnamon that may cause inflammation or chronic irritation/inflammation. Certain brands of toothpastes, mints, gums, candy, or mouth rinses may contain these flavoring agents in higher quantities. Work with the patient to find the best product for them.

- Advise the patient to keep a log of offending foods and any products that may cause the fissuring to become more severe or cause burning.

- Encourage the patient to keep and maintain scheduled dental hygiene appointments and oral cancer exams.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Figures 1, 2: Fissured tongue (courtesy of Carol Perkins, RDH, BA, AS, and Steven M. Chew, DDS)

Figure 3: Geographic tongue (courtesy of Dr. Harvey Kessler)

One study (Jarvinen et al., 2014) discusses the fact that the depth and clinical appearance of fissured tongue vary so greatly, it is difficult to determine when to classify a tongue as "fissured" and equally difficult to determine any measurements in order to classify these traits. A case (Binmadi et al., 2010) of fissured tongue suggested several considerations that should be included for a differential diagnosis (see related sidebar). The authors in the Binmadi study were able to attribute the fissuring to psoriasis and cautioned dental health-care providers to consider psoriasis in their differential diagnosis when appraising geographic tongue and tongues with noted fissuring.

Intraoral characteristics: A fissured tongue is sometimes called a scrotal tongue, a plicated tongue, or a grooved tongue, and may be associated with the entity known as geographic tongue (see Figures 1 and 2). The fissuring may be so deep that there is a lobulated appearance.

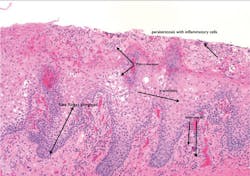

Histology: The rete ridges exhibit hyperplasia and inflammation in the lamina propria. Fissuring is often exhibited along with the characteristics of geographic tongue. There is loss of the keratin hairs on the filiform papillae with prominence of the fungiform papillae. Geographic tongue is characterized with microabscesses in the upper epithelial layers (see Figure 3).

Dental implications: As the population ages and life expectancy increases, more older adults will most likely be treated with medications for chronic disease states. The literature suggests that fissuring of the tongue increases with age.

Fissured tongue may cause debris to build up in the crevices and deep grooves of the tongue surface, making debridement difficult for the patient. The crevices harboring debris and bacteria make halitosis a possibility. Accumulation of debris in crevices may affect taste and food choices as well.

The sensation of taste is especially important from a nutritional perspective in older adults. Patients may note soreness or burning of the tongue with varying food sources or the use of certain dental products that are highly flavored.

Patient education: In addition to ruling out conditions that may be associated with fissured tongue, the clinician should educate the patient on the best techniques to lower inflammation and maintain the crevices as debris free as possible. Brushing the tongue with a very soft-bristle brush that allows the bristles to go into the crevices is optimal. Since many patients use an electric brush, this type of brush may be too abrasive to reach into deep crevices. So a separate soft brush would be best (child's soft brush). The use of a tongue cleaner can be recommended as well.

Although patients brush their tongues lightly in most cases, maintaining deep crevices will necessitate a more concentrated effort to remove debris. Sodium bicarbonate rinses may be recommended and, in the case of inflammatory tongue surfaces, antibacterial rinses. Some hypersensitivity to flavoring agents may also cause more inflammation, redness, and edema in the oral tissues. Eliminating these may improve the tissues of the tongue (Endo and Rees, 2007). Most doctors of osteopathic medicine and Chinese medicine believe that fissuring indicates a lack of hydration within the body, as well as nutritional deficiencies of certain food groups such as green vegetables. See sidebar for specific patient education information.

Patients may be concerned about the possibility of oral cancer and need reassurance that malignancy is not an issue associated with a fissured tongue. Psychological and self-conscious issues may exist for the patient because of the appearance of the tongue. Those areas with a fissured appearance toward the tip or the anterior one-third of the tongue may be more visible to the patient and noticed by others. Perhaps the patient has received comments, elevating these concerns. Assisting the patient in limiting inflammation, confirming any etiology, and, hopefully, decreasing the appearance of fissures is needed.

As always, remember to ask good questions and continue to listen to your patients! RDH

References

1. Binmadi NO, Jham BC, Meiller TF, Scheper MA. A case of a deeply fissured tongue. Oral Pathol, Oral Med, Oral Radiol, Endo. 2010; 109:5. 659-663.

2. Cawson RA, Odell EW. Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine. 6th ed. Churchill Livingstone, London. 1998.

3. DeLong L, Burkhart NW. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist 2nd edition. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore. 2013.

4. Endo H, Rees TD. Cinnamon products as a possible etiologic factor in orofacial granulomatosis. Med Oral Pathol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007 Oct 1;12:6: E440-4.

5. Jarvinen J, Mikkonen JJW, Kullaa AM. Fissured tongue: A sign of tongue edema? Medical Hypotheses 82, 2014: 709-712.

6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2014.03.010

7. Lynge Pedersen AM, Nauntofte B, Smidt D, Torpet LA. Oral mucosal lesions in older people: relation to salivary secretion, systemic diseases and medications. Oral Dis; 2015; Mar 7. Doi: 10.1111/odi.12337.

8. Picciani BLS, Souza TT, Santos VDCB, Domingos TA, Carneiro S, Avelleira JC, Azulay DR, Pinto JMN, Dias EP. Geographic tongue and fissured tongue in 348 patients with psoriasis: Correlation with disease severity. The Scientific World Journal. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/564326

9. Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. March, 2010, 81:5; 627-34.

10. Burkhart NW. Geographic tongue. http://www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-28/issue-10/columns/oral-exams/geographic-tongue.html

NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics, Baylor College of Dentistry and the Texas A & M Health Science Center, Dallas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (http://bcdwp.web.tamhsc.edu/iolpdallas/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. She was a 2006 Crest/ADHA award winner. She is a 2012 Mentor of Distinction through Philips Oral Healthcare and PennWell Corp. Her website for seminars on mucosal diseases, oral cancer, and oral pathology topics is www.nancywburkhart.com.