The underused block: The Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block is a viable pain control option

By Margaret J. Fehrenbach, RDH, MS, and Demetra D. Logothetis, RDH, MS

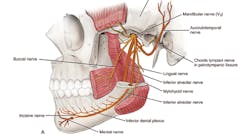

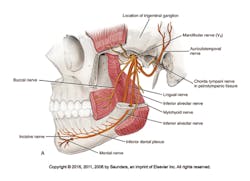

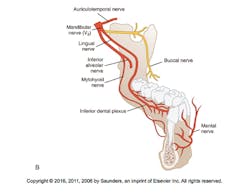

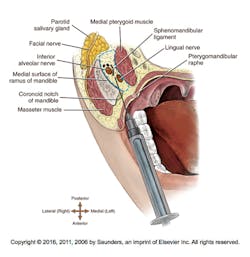

Figure 1: Pathway of the mandibular nerve or third division of the trigeminal nerve that is anesthetized by the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block from a lateral view (A) and from a medial view (B); note that most of the mandibular nerve is anesthetized except for the auriculotemporal nerve with the buccal nerve anesthesia being variable.2,3 (courtesy of Saunders/Elsevier)

Options always exist in executing dental hygiene care, including the administration of local anesthesia.1 But smart dental hygienists look to evidence-based outcomes for providing successful care to their patients. One of these viable options for patient pain control is a mandibular quadrant block, the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block or V-A block. Many clinicians believe that this is an underused block, which can be used routinely for many situations that present themselves when considering mandibular anesthesia.1,2,3,4

The V-A block anesthetizes many of the branches of the mandibular nerve that serve the mandibular arch with one injection. The mandibular nerve is the third division (V3) off the fifth cranial or trigeminal nerve; it is a short main trunk formed by the merger of a smaller anterior trunk and a larger posterior trunk within the infratemporal fossa deep to the base of the skull, before the nerve passes through the foramen ovale of the sphenoid bone.

The nerve branches of the mandibular nerve anesthetized with the V-A block include the inferior alveolar, lingual, mental, incisive, and mylohyoid nerves within the pterygomandibular space as well as the (long) buccal nerve approximately 75% of the time (see Figure 1).2,4 Thus it is not considered a true mandibular block, because it does not anesthetize the entire mandibular nerve and its branches as does the Gow-Gates (G-G) mandibular block.2,3,5 But many clinicians do not feel comfortable using the G-G block since it uses extraoral landmarks for its administration, and additionally anesthetizes the auriculotemporal nerve region with its added possible complications. In contrast, the V-A uses a more comfortable intraoral approach for its administration.2,3,4,6

And with its innervation, the V-A block is instead more similar to the inferior alveolar (IA) block in anesthetic coverage (see Figure 2). Therefore, the V-A block will anesthetize the mandibular teeth to the midline and associated lingual periodontium and gingiva, as well as the facial periodontium and gingiva of the mandibular anterior teeth and premolars to the midline and possibly the buccal periodontium and gingiva of the mandibular molars within one mandibular quadrant.2,3

In contrast to these other mandibular quadrant blocks, the V-A block is a closed-mouth block. Both the IA and G-G blocks require the patient to have his or her mouth open for administration of the block; the clinical effectiveness of the G-G block also requires the patient to maintain an open mouth after the injection for approximately one to two minutes. Thus, the V-A block has a major advantage over these other two mandibular quadrant blocks, since it allows clinically effective anesthesia of a patient who has severe trismus, which is a limited mandibular opening as a result of infection, trauma, or postinjection complication.2,3,5,8

The V-A block is also useful when soft-tissue structures, such as the tongue or buccal fat pad, persistently obstruct the view of the necessary intraoral landmarks used in the IA block (see Figure 3).2,3 In addition, this block can be used for the fearful patient who does not want to open for anesthesia or may not be able to hold his or her mouth open for the length of injection.2,3 Pain levels using the visual analog scale (VAS, which is a tool used to help a person rate the intensity of certain sensations and feelings such as pain) are similar to the other mandibular quadrant blocks, the IA and G-G blocks. This moderate level can be mediated by using pain control methods such as anesthetic buffering and nitrous oxide inhalation.2,3,7,9 In fact, one clinical trial found that the V-A block was "subjectively most acceptable to the patient."10

Finally, this mandibular quadrant block can be used if the patient has a history of IA block failure owing to accessory innervation. There is greater clinical effectiveness with the V-A block than the IA block with many cases since the mylohyoid nerve is anesthetized, which has been associated with accessory innervation of the mandibular first molar.2,3,4,5,11 However, the V-A block is contraindicated in patients with an acute infection or inflammation within the pterygomandibular space or maxillary tuberosity region.2,3,4,12

Additional administration of the buccal block to anesthetize the associated buccal periodontium and gingiva of the mandibular molars may also be indicated in a few cases to complete the mandibular quadrant anesthesia similar to the IA block.1,4 Now that the patient is relaxed by the loss of trismus or even reduction of fear, the buccal block will now be easier to administer since it is an intraoral block that is not hampered by soft tissue structures (see earlier discussion).

Target Area, Injection Site

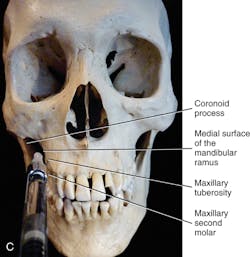

The target area or deposit location for the V-A block is the medial surface of mandibular ramus within the pterygomandibular space approximately halfway between the mandibular foramen and the neck of the mandibular condyle, as well as being adjacent to the maxillary tuberosity (see Figure 4 and procedure sidebar).

Figure 2: Distribution of anesthesia by the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block is highlighted. This includes the mandibular teeth to the midline and associated lingual periodontium and gingiva, as well as the facial periodontium and gingiva of the mandibular anterior teeth and premolars to the midline within one mandibular quadrant. Note that this is also the same intraoral area anesthetized by the inferior alveolar block with the additional anesthesia of the mylohyoid nerve of area muscles and, in some cases, the accessory innervation of the mandibular first molar. The buccal periodontium and gingiva of the mandibular molars are also possibly anesthetized.2,3 (as shown) (courtesy of Saunders/Elsevier)

Figure 3: An obstructing tongue and/or buccal fat pad on one patient was noted during palpation by the cotton swab before the administration of an inferior alveolar block during two separate appointments. These persistently individualized anatomic features prevent the clinician from viewing the necessary intraoral landmarks for that block. This could prevent the needle from accessing the target area of the pterygomandibular space. Consideration of using the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block was then pursued for future dental hygiene care on the patient's mandibular arch. These obstructions can be commonly noted on many patients. (courtesy of Margaret J. Fehrenbach, RDH, MS)

The patient is asked to gently occlude the posterior teeth, with the muscles of mastication remaining as relaxed as possible. If the muscles are clenched, the pterygomandibular space will be obliterated, which will prevent the agent from contacting the nerves within it.2,3,4 The intraoral landmarks must be visible during the injection so retraction of the cheek and its buccal fat laterally is needed, and using a retractor instrument is highly recommended. However, this lateral retraction is much easier to obtain in this manner than the retraction needed for the IA block. The intraoral landmarks for the V-A block are the bone of the medial surface of the mandibular ramus, maxillary tuberosity, and mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar.

Figure 4: Target area for the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block is the medial surface of the mandibular ramus within the center of the pterygomandibular space (A) at approximately halfway between the mandibular foramen and neck of the mandibular condyle (dashed line with circle) (B) as well as being adjacent to the maxillary tuberosity (C).2,3 (courtesy of Saunders/Elsevier)

The injection site or needle insertion point is the buccal mucosa between the medial surface of the mandibular ramus and the maxillary tuberosity, with the syringe parallel to the maxillary occlusal plane (see Figure 5). Thus this injection is administered at a site more inferior than the G-G block but more superior than the IA block.

The injection height of the V-A block is determined by placing the needle at the same height as the mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar directly across the way (see Figure 6).

The needle, with the bevel oriented away from the bone of the mandibular ramus so it faces toward the midline, is directed medially past the coronoid process and then inserted into the buccal mucosa at the established height. The needle is then advanced posteriorly and slightly laterally without contacting the medial surface of the bone of the mandibular ramus unlike the IA block, with the hub of the syringe ending up opposite the mesial aspect of the maxillary second molar (see Figure 7). The needle will naturally deflect toward the mandibular ramus so that the needle will remain in close proximity to the IA nerve for the highest level of clinical effectiveness.2,3,4

Due to the closed-mouth situation, it may be difficult to visualize the path of the needle, so depth of the needle is always a concern and must be carefully controlled; the depth is approximately half the mesiodistal length of the mandibular ramus as measured from the maxillary tuberosity (see next discussion). The depth of insertion is approximately 25 mm or two-thirds to three-fourths of a long needle for the average-sized adult with the distance measured from the maxillary tuberosity; in smaller or larger patients, this depth of penetration should be adjusted to more or less (see Figure 8).3,4 Thus the depth of insertion will vary with the anteroposterior size of the patient's mandibular ramus.2,3,4

As with the IA block, there should be no bending of the needle shank toward the lateral with the V-A block to accomplish the necessary needle and syringe barrel angulations as discussed.3,4 The needle can break when bent and there is little control over the needle direction, needle angulation, and needle bevel. Nor should any change in direction of the needle within the tissue to obtain correct angulation be performed as this may cause trauma. Correct angulations should be ascertained before entering the soft tissue.

With the needle tip within the center of the pterygomandibular space, the injection is administered (Figures 7, 8). The goal of the block is to fill the space with the agent so as to get full contact of the agent with the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves within the space.2,4 In addition, putting the patient upright or semiupright after the injection also helps the agent diffuse by gravity into the region, similar to the IA block.2,3

Troubleshooting

Similar to the IA and G-G blocks, a troubleshooting paradigm may be used to achieve clinical effectiveness with the V-A block. Although no bone should be contacted with this block, as discussed, if the mandibular ramus obstructs needle placement, it often occurs early. It is usually due to contact with the outer coronoid process since the insertion point is too far laterally placed; it may be corrected by reinserting the needle at a more medial position.2,3,4

However, if the needle is placed too medially, it will end resting medial to the sphenomandibular ligament and only the superficial lingual nerve will become anesthetized and not the deeper IA nerve (see Figure 8).2,3,4 This latter case mainly occurs when injecting on the nondominant side of the mouth due to even less visibility of the intraoral landmarks. Again, the clinician needs to establish the correct and most clinically effective pathway of the needle and syringe barrel to achieve placement within the pterygomandibular space. Thus administering the agent too early and with the needle too shallow will cause this same situation with its lack of depth to the anesthesia.

Out of a concern for the risk of complications, the clinician may also inject the agent at too inferior a position, again similar to the IA block. To correct this situation, the insertion of the needle can be at or slightly above the level of the mucogingival junction of the maxillary second or third molar across the way.2,3,4

If there is still discomfort during dental procedures, the V-A block can be readministered if there is still trismus present. If trismus has subsided for the patient but discomfort is still present, then an IA block or G-G block can be administered instead.2,4,5

Indications/Possible Complications

Indications of a clinically effective V-A block allow for anesthesia and numbness that is very similar to that of the IA block. And since motor nerve paralysis develops as quickly as, or quicker than, sensory anesthesia; the patient with trismus begins to notice increased ability to open the jaws shortly after the deposition of anesthetic.2,3,4,5

There is a decreased risk of positive aspiration as well as hematoma formation as compared to the IA block since the IA artery and vein are farther away from the injection site than they are with the IA block. It is also less traumatic than the G-G block with the mouth needing to stay open (see earlier discussions).2,3,4 A hematoma develops when a blood vessel, particularly an artery, is punctured or lacerated by the needle. This is observed as a short-term but slightly disfiguring asymmetrical swelling and then discoloration of the tissue resulting from the effusion of blood into extravascular spaces.2,13

Figure 5: Injection site for the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block is palpated at the buccal mucosa with the injection height at the same height as the mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar directly across from the tooth.2,3 (courtesy of Elsevier)

Figure 6: Determining the injection height of the Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block by placing the needle at the same height as the mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar directly across the way. Using a retractor instrument is highly recommended.2,3 (courtesy of Elsevier)

Figure 7: Needle insertion during a Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block at the buccal mucosa between the bony surfaces of the medial surface of the mandibular ramus and the maxillary tuberosity, with the syringe barrel parallel to the maxillary occlusal plane. The needle was first directed medially past the coronoid process. The exact insertion point is hard to discern due to buccal frenum interference. The needle is advanced posteriorly and slightly laterally without contacting the medial surface of the mandibular ramus, and with the hub of the syringe ending up opposite the mesial aspect of the maxillary second molar. The syringe is stabilized by the clinician resting the pinky of the dominant hand on the patient's chin.2,3 (courtesy of Elsevier)

Figure 8: Needle insertion into the midsection of the pterygomandibular space (dashed line) during a Vazirani-Akinosi mandibular block without contacting the bone of the medial surface of the mandibular ramus unlike the inferior alveolar block. The depth of the needle is approximately half the mesiodistal length of the mandibular ramus as measured from the maxillary tuberosity. However, if the needle is inserted too far posteriorly, it may enter the parotid salivary gland containing the seventh cranial nerve or facial nerve, causing the complication of transient facial paralysis.2,3 (courtesy of Saunders/Elsevier)

However, depth of the needle must be considered to avoid administration of anesthetic into the parotid salivary gland located at the posterior border of the mandibular ramus, anesthetizing the facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) that travels through the parotid salivary gland (see again figure 8).2,3 Important steps must be taken to ensure its correct pathway that were discussed earlier in order to prevent the inadvertent deposition of anesthetic solution by overinsertion into the parotid salivary gland. If these are not taken into account, the complication of transient facial paralysis may occur. With this more minor complication that can also occur with the IA block,, the patient will experience a weakening of the muscles of facial expression on the injection side, and lack of anesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve. This finally produces a unilateral loss of motor function to the muscles of facial expression.

The loss of motor function is temporary and fades within a few hours once the action of the local anesthetic resolves. During this time, the patient will be unable to use these facial muscles and will have a lopsided appearance; however, the corneal reflex remains functional and continues to produce tears to lubricate the eye. At the point of muscle weakening, the patient will be alarmed and immediate reassurance is necessary to alleviate the patient's fears. The eye may need to be manually closed after any contact lenses have been removed.

As we know from our past training in local anesthesia as dental hygienists, if you have a patient with trismus that requires anesthesia of a mandibular quadrant for emergency restorative care, the clinician should consider administering the V-A block. However, fearful patients who do not want to open for anesthesia or may not be able to hold their mouth open for the length of an IA or G-G block for anesthesia of the mandibular quadrant are also candidates for this block before dental hygiene care.

In addition, if you have dental hygiene patients who require this region of local anesthesia but have soft-tissue structures such as the tongue or buccal fat pad persistently obstructing the view of the intraoral landmarks for the IA block, try using this block. Or, if you just do not feel comfortable using the G-G block due to its extraoral landmarks, the V-A block uses intraoral landmarks instead, so it may be your new go-to block.

Finally, this mandibular block can be used if the patient has a history of IA block failure owing to anatomic variability or accessory innervation. It's one mandibular block with so many options for its use to consider! As one noted clinician stated: "Having the skill to perform these alternative anesthetic techniques increases the (clinician's) ability to provide successful local anesthesia consistently for all procedures in mandibular teeth."4

How does the dental hygienist who is now in private practice and licensed to administer local anesthesia learn to administer this option of the V-A block? Possibly a continuing-education opportunity with a hands-on element will present itself. Or, after thoroughly studying the steps and practicing with a cotton swab, a knowledgeable fellow dental hygienist or supervising dentist in the practice can assist with the initial injection on a patient who has given informed consent before a procedure needing the local anesthesia. However, a group of licensed dental hygienists can also form a local study club with a knowledgeable peer facilitator (possibly working within a clinical situation on patients who have given informed consent again before a procedure needing the local anesthesia) following the guidelines of their state regulations as to the necessary dental supervision required. As in all cases, state regulations concerning local anesthesia for dental hygienists must be checked before administering this option.

Editor's Note: To continue the discussion on this mandibular block, listen to Fehrenbach present the seminar, "Expanding your options: Should I add the AMSA or V-A blocks to my every repertoire?" at the 2016 RDH Under One Roof (RDHUnderOneRoof.com). RDH

Steps for Vazirani-Akinosi

Mandibular (V-A) Block Procedure

Step 1

Assume the correct clinician positioning for both right and left sides at 8 o'clock for a right-handed clinician or 4 o'clock for a left-handed clinician.

Step 2

Ask the supine patient to gently occlude the posterior teeth, with the muscles of mastication remaining as relaxed as possible. After retracting the cheek with a retractor instrument as much as possible, locate the intraoral landmarks: medial surface of the mandibular ramus, maxillary tuberosity, and mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar (see Figures 4 and 5).

Step 3

Prepare the buccal mucosa at the injection site or needle insertion point on the medial surface of the mandibular ramus within the pterygomandibular space adjacent to the maxillary tuberosity (see Figure 5 and the references for more specific information).

Step 4

Using a 25-gauge long needle, orient the bevel of the needle away from the bone of the mandibular ramus so that it faces toward the midline with the large window toward the clinician.

Step 5

Direct the syringe barrel parallel to the maxillary occlusal plane and medially past the coronoid process. Then the needle is placed at the same height as the mucogingival junction of the maxillary third or second molar directly across the way to determine the height of the injection (see Figure 6).

Step 6

Establish a fulcrum by resting the pinky of the dominant hand on the patient's chin (see Figure 7).

Step 7

The needle is then inserted into the buccal mucosa at the established height. Advance the needle posteriorly and slightly laterally without contacting the bone of the medial surface of the mandibular ramus with the hub of the syringe, ending up opposite the mesial aspect of the maxillary second molar. The depth is approximately half the mesiodistal length of the mandibular ramus as measured from the maxillary tuberosity at approximately 25 mm or two-thirds to three-fourths of a long needle for the average adult with the distance measured from the maxillary tuberosity; in smaller or larger patients, this depth of penetration should be adjusted (See Figure 7).

Step 8

Aspirate within two planes (see references for more specific information).

Step 9

If negative aspiration is achieved, slowly deposit approximately 1.8 mL or one cartridge over 60 to 120 seconds.*

Step 10

Carefully withdraw the syringe and immediately recap the needle using the one-handed scoop method using a needle sheath prop (see references for more specific information).

Step 11

Place the patient upright or semi-upright, rinse the mouth, and wait approximately three to five minutes until anesthesia takes effect before starting treatment. If there is lack of clinical effective anesthesia or the patient feels uncomfortable during treatment, proceed with the troubleshooting injection paradigm (see earlier discussion).

* Approximate recommended doses stated are for 2% solutions of local anesthetic agents for adults; if using 4% solutions of local anesthetic agents, it is recommended to lower the dose (see references for more specific information).

Demetra Daskalos Logothetis, RDH, MS, is emeritus professor and program director at the University of New Mexico Department of Dental Medicine, and is currently a part-time professor and graduate program director in the university's Division of Dental Hygiene. Demetra has been a professor at the University of New Mexico for 29 years, and served as the dental hygiene program director for 16 years. She has been teaching local anesthesia for 20 years, and currently teaching local anesthesia certification courses across the country. She is is the author of "Local anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist," (Elsevier, ed 2, 2017). This textbook is exclusively related to local anesthesia for the practice of dental hygiene.

Margaret J. Fehrenbach, RDH, MS, is an oral biologist and dental hygiene educational consultant. She is also currently an adjunct faculty member at Seattle Central College in Seattle in its Bachelor of Applied Science in Allied Health Degree Program (with Emphasis in Dental Hygiene). Margaret recently received the AC Fones Award from ADHA (2013) for her work in promoting local anesthesia for dental hygienists, such as "Local anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist" (Elsevier, second edition, 2017) as well as the ADHA Award of Excellence (2009) for her textbook contributions. She is the primary author of the "Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck" (Elsevier, ed 5, 2017) and "Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy" (Elsevier, ed 4, 2015) as well as a contributor to "Oral Pathology for Dental Hygienists" (Elsevier, ed 7, 2018) and editor of the "Dental Anatomy Coloring Book" (Elsevier, ed 2, 2013). Margaret has presented at ADEA, ADHA, and ADA Annual Sessions as well as Under One Roof for RDH Magazine. She is now involved in webinars and social media outlets. She can be contacted through her webpage at www.dhed.net. References

1. Logothetis DD, Fehrenbach MJ. Local anesthesia options during dental hygiene care. RDH Magazine. June 2014.

2. Fehrenbach MJ, Herring SW. Illustrated anatomy of the head and neck, ed 5, Saunders/Elsevier, 2017.

3. Fehrenbach MJ, Logothetis DD. Chapters: Anatomic Considerations. Mandibular Anesthesia. Editor: Logothetis DD, Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist, ed 2, Elsevier, 2017.

4. Haas DA. Alternative mandibular nerve block techniques: a review of the Gow-Gates and Akinosi-Vazirani closed-mouth mandibular nerve block techniques. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(Suppl 3):8S-12S.

5. Malamed S. Handbook of local anesthesia, ed 6, St Louis, Mosby/Elsevier, 2013.

6. Fehrenbach MJ. Gow-Gates mandibular nerve block: an alternative in local anesthetic use. Access (ADHA). 2002;34-37.

7. Jacobs S, et al. Injection pain: comparison of three mandibular block techniques and modulation by nitrous oxide: oxygen. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(7):869-876.

8. Fehrenbach MJ, contributor. Extraoral and intraoral patient assessment. In Darby ML, Walsh MM, editors: Dental hygiene theory and practice, ed 4, Philadelphia, Saunders/Elsevier, 2015.

9. Fehrenbach MJ. Pain control for dental hygienists: Current concepts in local anesthesia are reviewed. RDH Magazine. February 2005.

10. Johnson TM, et al. Teaching alternatives to the standard inferior alveolar nerve block in dental education: outcomes in clinical practice. Thomas M. Johnson, J Dent Ed. 2007;71(9):1145-1152.

11. Madan GA, et al. Failure of inferior alveolar nerve block: exploring the alternatives. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(7):843-846.

12. Fehrenbach MJ, Herring SW. Spread of dental infection. Journal of Practical Hygiene. September/October 1997.

13. Fehrenbach MJ, contributor: Chapters: Inflammation and repair. Immunity. In Ibsen OC, Phelan JA, editors, Oral Pathology for Dental Hygienists, ed 7, Saunders/Elsevier, 2018.

NOTICE: Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Clinicians and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information and methods as well any drug or pharmaceutical products identified described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. To the fullest extent of the law, the authors of this article as well as those referenced nor the publishers and editors of this article assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.