Occupationally acquired HIV

by Charles John Palenik

As of December 2001, there were 23,951 cases of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) in the United States among individuals with a history of employment in health care. This represents approximately 5.1 percent of the 469,850 AIDS cases for which employment information is known. Employment information for the other 337,225 reported cases is unknown.

Specific job types are known for more than 22,420 health care workers (HCWs). Included are 1,760 physicians, 5,211 nurses, 6,365 health aides, 3,086 technicians, 463 paramedics, and 199 surgeons. A total of 486 dental workers (dentists, hygienists, assistants, and laboratory technologists) have had AIDS. Over 73 percent of HCWs with AIDS have died.

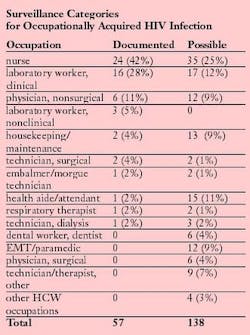

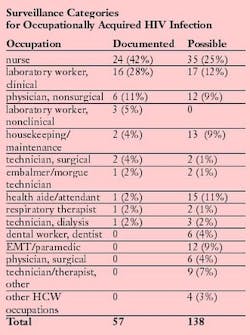

There have been 57 documented cases of HCWs seroconverting to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive after an occupational exposure. Because formal evidence of seroconversion or genetically similar strains of viruses is necessary for classification as documented occupational HIV infection, no cases before 1985 can be verified. To date, 26 of the HCWs have developed AIDS. None of the documented cases involved dental personnel.

Forty-eight (84 percent) of the HCWs sustained a percutaneous (puncture/cut injury) exposure. Two had percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposures, while six had mucocutaneous exposures only. Risk of transmission increases when hollow bore needles are involved, especially if obviously soiled with blood, or if they had been inserted into an artery or vein or caused a deep tissue injury. It is also important if the source patient dies within two months of the exposure. Generally, the greatest concentration of HIV in blood (viral load) occurs soon after infection (acute retroviral syndrome) and during the AIDS stage of HIV disease.

Prospective studies of HCWs suggest that the average risk of HIV transmission is approximately 0.3 percent (one in 333) after a percutaneous exposure to HIV-positive blood. The rate is 0.09 percent after a mucous membrane exposure. Suture needles have not been implicated as a source of infection; however, occupational HIV infection has been reported among surgical personnel. Solid sharps, such as hand instruments and burs, cause most blood exposures among dental workers. Such exposures usually involve relatively small amounts of blood.

In addition to documented cases, 138 possible cases of occupational acquisition have been noted. Possible cases involve persons who have had an exposure to HIV-containing blood or body fluids and no known identifiable behavioral or transfusion risks. However, HIV seroconversion to a specific exposure cannot be documented. The number of these HCWs who acquired their infection through an occupational exposure is not known. There are six possible dental worker cases.

Since June 2001, no new documented cases and only one new case of possible occupational transmission were reported. The number of possible transmission cases may decrease if individuals are reclassified when a nonoccupational risk is identified or may increase if new cases are reported.

Of the 57 documented HCW cases, eight received postexposure prophylaxis (PEP). Seven of the eight completed a recommended PEP regimen. There is some encouraging data concerning the efficacy of PEP, especially if treatment is initiated promptly and involves two or more antiretroviral drugs. The true value of PEP is not known because protection is not universal. Worldwide, there are 21 reports of HIV infection, despite PEP.

Over 50 percent of HCWs reported adverse events while taking antiretroviral drugs prophylactically, and about one-third failed to complete the full course of treatment. Most symptoms were not serious and could be managed.

Although rare, significant — even life threatening — side effects can occur. Prophylactic regimens using three drugs cause more side effects than those using two.

It is unclear why 99.7 percent of all percutaneous occupational exposures do not end in infection. Empirically evident factors, such as the HCW's immune status and various characteristics of the viral strain involved, have not been well described. Neither the size of the window of opportunity after exposure to HIV, nor the optimal length of PEP is known. The safest and most effective forms of PEP have yet to be elicited.

In the last 20 years, much has been learned about HIV transmission and how occupational exposures occur. Major improvements in HCW safety on the job have resulted, especially in the area of infection control.

On November 6, 2000, Congress passed the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act. It directed OSHA to revise the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard to describe in greater detail its requirement for employers to identify and make use of effective and safer medical devices. The act requires employers to update their responses in four areas: addition of new/changed definitions; exposure control plan revisions; solicitation of input from employees; and changes in sharps injury reporting.

The leading source of safety and health information for dental practices, the Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures (OSAP) offers a wealth of compliance information via newsletters, training systems and Web site ( www.osap.org). In 2002, OSAP produced an important position paper, Percutaneous Injury Prevention.

Charles John Palenik, MS, PhD, is an assistant director of Infection Control Research and Services at the Indiana University School of Dentistry. Dr. Palenik has authored numerous articles, book chapters and monographs, and is the co-author of the popular Infection Control and Management of Hazardous Materials for the Dental Team. He serves on the Executive Board of OSAP, dentistry's resource for infection control and safety.Questions about this article or any infection control issue may be directed to [email protected].