Burning Mouth Syndrome

by Nancy W. Burkhart, BSDH, EDD

Your patient today has been a patient of record for many years within your practice. Ella is a 60-year-old female who has a scheduled maintenance appointment. Her complaints at the appointment concern a burning sensation in her mouth, specifically within her tongue. She has also noticed some difficulty in swallowing, noticeable dysguesia (a distortion of the sense of taste), and feels that her mouth is dry even though she senses the presence of saliva.

------------------------------------------------

Other articles by Nancy Burkhart

------------------------------------------------

As you begin to examine Ella's mouth, you really do not see any abnormality. Since you have seen her numerous times in the past, you are familiar with the appearance of her oral tissues and her teeth. Ella does take an over-the-counter medication for reflux disease and occasionally uses an over-the-counter medication for minor aches and pains. Otherwise, she appears to have no other medical conditions as you review her health history. Your comprehensive exam leads you to no other significant or unusual findings.

As you inspect the teeth, no sharp edges or broken restorations appear to be a factor in her stated burning sensation. Ella's tongue appears to have a slight coating with highly visible fungiform papillae, but the surface appears normal. Palpation of the tongue renders no additional information related to the burning sensation. You notice that she is not chewing on the lateral borders of the tongue or the tip of the tongue. But she is complaining about both locations causing her to have a burning and tingling sensation. Ella tells you that her symptoms are much better in the morning and tend to worsen toward the evening. She believes that this is also affecting her sleep at night.

The lack of a visual clue leaves you perplexed. Could Ella have burning mouth syndrome?

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is generally reported by a patient who complains of burning, stinging, or tingling sensations in the mouth. The patient may report a dry mouth and altered taste sensations as well. BMS affects nearly 1.3 million Americans. However, the rates worldwide vary greatly, and the inconsistency in diagnostic factors and study methods make a true representation questionable. The prevalence of the general population may be approximately 0.7% to 5%. This rate is higher than some autoimmune diseases! Since a universally accepted diagnostic criterion is not available, the prevalence is rather skewed. BMS affects women 2.5 to 7 times more often than men. The disorder has a predisposition for women who are post or peri-menopausal, with higher rates noted at 3 to 12 years post menopause. In Europe, there is an estimated rate of BMS in 12% of older women (Zur, 2012).

Causes of burning mouth syndrome

The diagnosis for BMS is usually made after taking a careful history, performing a physical examination and conducting laboratory analysis. A diagnosis is made by the elimination of disease processes and by determining possible etiology of relevant factors. After ruling out other etiology, a practitioner can offer some advice or treatment for the burning sensation. The diagnostic and treatment process is often time-consuming since this is a very complex disorder of orofacial sensation, making it rather subjective.

BMS typically involves the anterior two-thirds of the tongue but may also involve and extend into the lips, hard palate, and locations in the oral mucosa. Generally, the disorder is considered to be an idiopathic pain condition. This means that the nerve fibers are functioning in an abnormal fashion. BMS has been linked to alteration and deviation in the nerve supply to the tongue. At this time, the general consensus is that BMS is a form of neuropathy resulting in chronic pain. Neurological, psychogenic, or hormonal factors all appear to contribute to the disorder of BMS.

Burning mouth syndrome is a multifactorial disorder and may also include nutritional components, endocrine, psychological diseases, infections, and iatrogenic causes. Medications such as ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may trigger the development of BMS. Nevirapine and efavirenz, used in HIV treatment, have been implicated as well. Additionally, Levodopa, used to treat stiffness, shakiness, and slow movement may be implicated in the development of BMS in patients with Parkinson's disease.

The International Headache Society (2004) defined primary BMS as "an intraoral burning sensation for which no medical or dental cause can be found" (Gurvitis, et al. 2013).

Two forms of BMS have been labeled and denoted as:

- Primary, in which a cause cannot be identified

- Secondary, a form involving disease states such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, psychiatric illnesses, infections, drug use, dental treatment, vitamin or mineral deficiencies, and gastrointestinal diseases.

GERD and urogenital problems have also been associated with BMS (Thoppay, et al. 2013). Recent studies indicate patients with BMS had a statistically higher intake of medications for gastric disease compared to a control group.

Others suggest three forms of BMS: Type 1 related to nutritional deficiencies; Type 2 to chronic anxiety; and Type 3 to dietary or prosthetic allergies.

Klasser, et al. 2011 presented a diagnostic algorithm that explores local factors, systemic factors, and psychological factors that should be ruled out in both the primary and secondary forms of BMS when making a diagnostic evaluation. The retrospective study suggests the etiology of BMS within this patient population of study:

- 27% related the onset to a dental treatment

- 16% related the onset to a new medication

- 14% related the onset to a medical or personal event (stressor)

- 43% related the onset to an unknown cause

The stated causes are typical while upper respiratory issues were also implicated on occasion. Patients in this particular study also reported medical conditions such as hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hypercholesterolemia, autoimmune disorder, thyroid disorder, and anemia.

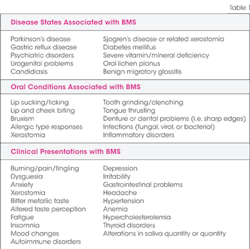

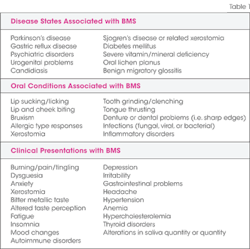

Initial tests that should be considered before a firm diagnosis of BMS can be given are testing for blood disorders; oral samples and cultures to rule out bacterial, viral or fungal etiology; allergy testing; medication analysis; and biopsy if needed, Generally, BMS is related to three categories of etiology that need to be determined: Local factors, systemic factors, or psychological factors. Once these factors have been considered and eliminated, a diagnosis of BMS may be rendered (see Table 1).

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment for BMS varies with the diagnosed type of the disorder. Three paths usually result with any treatment:

- Some patients show significant change

- Some show no improvement

- Others appear to worsen in their symptoms.

Although there is no known cure, the discomfort is alleviated with a variety of medications. Some of the medications are those used to treat depression and neurological disorders, such as clonazepam. Since the nerve fibers are excited, the medications may calm the impulses and assist in reducing anxiety.

Additional approaches are yoga, stress management, exercise, and psychotherapy. If nutritional deficiencies such as iron, B12, folic acid, Zinc, B complex are determined, supplemental vitamins are needed. Medications are often prescribed such as those listed in Table 2.

Herbal treatments have also been tried with some success such as St. John's wort and capsaicin. Alpha lipoic acid (ALA), a mitochondrial coenzyme with antioxidant effects, has been shown to be neuoprotective in previous studies on diabetic neuropathy, and there is some support for ALA in studies for the treatment of BMS (Femiano, et al. 2002). Acupuncture and biofeedback are also recognized as beneficial for some patients. Mouth guards worn at various times may be beneficial for some patients in controlling harmful oral habits, and, of course, there are combinations of all of the approaches mentioned.

Burning mouth syndrome is a multifactorial disorder that is difficult to diagnose, very time consuming for the health-care practitioner, and frustrating for the patient who is suffering with the disorder. The burning/stinging of the oral tissue is very problematic for the patient and alters the lifestyle for most individuals.

A multidisciplinary approach is needed with physicians, dentists, dental hygienists, and psychology professionals. A diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome is rendered only after all other possible oral, psychological, and systemic causes have been ruled out. Patients may experience BMS for short periods or for years with intermittent episodes. BMS has a significant impact on the quality of life of the typical patient. For this very reason, patient education about the disorder is crucial for the total health of the patient.

As always, ask good questions and always listen to your patients. RDH

NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics, Baylor College of Dentistry and the Texas A & M Health Science Center, Dallas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (http://bcdwp.web.tamhsc.edu/iolpdallas/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. She was a 2006 Crest/ADHA award winner. She is a 2012 Mentor of Distinction through Philips Oral Healthcare and PennWell Corp. Her website for seminars on mucosal diseases, oral cancer, and oral pathology topics is www.nancywburkhart.com.

References

Femiano F, Scully C. Burning mouth syndrome (BMS): Double blind controlled study of alpha-lipoic acid (thioctic acid) therapy. J Oral Pathol Med 2002; 31(5):267-269.

Gilpin SF. Glossodynia JAMA 1936; 106:1722-1724.

Gurvitis GE, Tan A. Burning mouth syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2013. Feb 7; 19(5): 665-672.

Klasser GD, Epstein JB, Villines D. Diagnostic dilemma: The enigma of an oral burning sensation. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b146.

Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Andujar-Mateos P. A prospective randomized study on the efficacy if tongue protector in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis 2011;17:277-282.

Thoppay JR, De Rossi SS, Ciarrocca KN. Burning mouth syndrome. Dent Clin N Am.

2013: 57;497-512.

Zur E. Burning mouth syndrome: a discussion of a complex pathology. Int J Pharm Compd. 2012; 16:3:196-205.

Past RDH Issues