It’s all about the angles: A biomechanical explanation of workplace body pain

The angles that are used (or not) to achieve neutral body posture during clinical practice are deeply rooted in geometry, biomechanics, and ergonomic practices. Biomechanics is the understanding of the fundamental principles of human motion.1 It considers the components of the musculoskeletal system and all the forces, torques, pressures, and stresses to understand the mechanical aspects of biological processes. In other words, it’s how we use our bodies.

The number one reported area in studies about dental hygiene body pain is the neck at 66%–68%, followed by the lower back at 61%–68%.2 Everything in the body is connected, from the hands to the neck. When we lunge our head out in front of the body, we begin a cycle of cellular death from a lack of oxygen, innervation, and nutrients to the cells in the area.

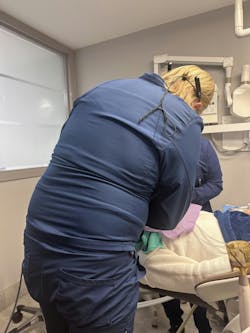

We compound these effects when we add another out-of-neutral angle and pivot our face down to see into the oral cavity. With each angled body part that is held out of neutral, we further compound the damage while expediting the symptoms of that damage. Here I’ll address the biggest pain—the neck.

The differences in two practicing hygienists

I’ll feature two hygienists named Heidi and Helga in my example. Heidi practices with her head forward and down by 60 degrees, and she rarely has her arms out to the side (abducted). Helga practices with her head forward and down by 60 degrees, and she routinely abducts her arms and leans forward at the hip. The pain-free career longevity for Helga is significantly less due to her holding multiple out-of-neutral body angles. Helga will likely feel pain sooner.

Since people have their own preferences, we must think about different equipment use. Continuing with the example, Heidi uses reading glasses to practice and therefore maintains a 60-degree forward head flexion. Helga tries to fix her pain with a pair of traditional TTL loupes that place her head at a 20-degree forward head flexion. If Helga makes no other changes, she’s likely to slow, but not eliminate, her momentum toward pain. It may still come sooner than Heidi’s because she has multiple angle issues, as many people who use traditional loupes have discovered.

The problem with loupes

As an ergonomics assessment specialist, I’m often asked during ergonomic training, “Why aren’t my loupes working?” Despite the use of traditional loupes, up to 93% of hygienists still report body pain.3 Why is this? The 20-degree forward head flexion found in traditional loupes is a biomechanical error. It’s better than 60 degrees, but still not neutral. It’s the perio equivalent of a 5 mm pocket.

The fact is that 20 degrees of cervical spine flexion is equivalent to approximately 20 pounds of pressure on the vertebral discs in the neck. This may have been considered safe when that’s all that was offered, but we have true safety now with prismatic ergo loupes that put zero pounds of pressure on our spine due to a 0-degree forward head flexion.

In our example, let’s add Henry RDH. Henry uses prismatic loupes that hold his head perfectly neutral, he keeps his arms down, and he practices in neutral body angles. As a result, he can expect to have very little body pain unless he works too many days and hours without rest, which is also an ergonomic no-no.

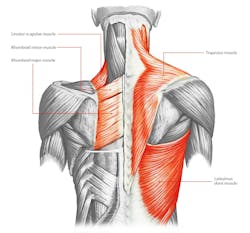

The body’s muscles

There are chains of muscles in the body that work together. As a personal trainer who specializes in posture correction, I see these chains in constant threat of neuromuscular patterns that cause damage, sometimes permanently. A chain example is the posterior chain. This includes the deep cervical muscles of the neck, the levator scapulae that interact with the shoulders, the spinal erectors and upper trapezius that begin at the back of the neck and go down to the lumbar vertebrae, and the glutes that begin at the hips and end at the back of the thigh where the hamstrings go to the back of the knee. Following are the calf muscles, and last but not least, the muscles of the ankles and feet.

The muscles in the chain are a group of muscles that are highly supportive of one another. When the head goes forward, the neck muscles engage, which signals the other muscles in the chain for support. Everything in the body works together to support the entire system, even to its own detriment. If multiple areas of muscle are heavily used, those muscles fatigue and fail with an eventual result of pain and loss of function.

But wait. There’s more.

How we interact with the oral cavity is also angle dependent. When looking at the maxillary linguals on our nondominant side, it’s necessary to have indirect vision and have the patient turn away to avoid angling the head to see directly. Seeing the mandibular lingual molars on our dominant side is also aided by indirect vision and the patient turning their head toward you. Don’t compensate the angles in your neck to avoid asking a patient to turn their head for a moment. Both of your comfort levels depend on it, but only you know where the patient needs to move.

How to keep your angles neutral

1. Reduce the biomechanical angles of the body while practicing—arms down, shoulders even, hips even, feet flat, wrists straight.

2. Use equipment that helps you work with your entire body in neutral—prismatic loupes, saddle stools, and a dual articulating head rest on the patient chair that is in supine.

3. Move the patient’s head. Say “turn to the right/left” or “look up.” Avoid saying “a little.”

4. Use and master indirect vision. This is nonnegotiable.

5. The more you practice, the better you will perform a skill. This includes being kind to yourself as you learn a new skill.

How we hold our bodies during practice is what ultimately determines injury, pain levels, and longevity as dental hygienists.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the June 2024 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

1. Innocenti B. Biomechanics: a fundamental tool with a long history (and even longer future!). Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2018;7(4):491-492. doi:10.11138/mltj/2017.7.4.491

2. Hayes MJ, Smith DR, Taylor JA. Musculoskeletal disorders in a 3 year longitudinal cohort of dental hygiene students. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88(1):36-41.

3. Hayes, M., Cockrell, D. and Smith, D. A systematic review of musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:159-165. doi.10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00395.x

About the Author

Katrina Klein, RDH, CEAS, CPT

Katrina is an 18-year registered dental hygienist, national speaker, author, competitive bodybuilder, certified personal trainer, certified ergonomic assessment specialist, and biomechanics nerd. She’s the founder of ErgoFitLife, where she teaches that ergonomics and fitness are a lifestyle to prevent, reduce, and even eliminate workplace pain. You can reach Katrina at [email protected].