Have you ever found yourself reviewing a medical history unsure if the patient requires antibiotic prophylaxis (AP)? You excuse yourself from the operatory to consult with the dentist and end up on the phone with the patient’s physician trying to determine if AP is indicated. Next thing you know, half of the appointment time has been taken up trying to find out if the patient can be seen today. Many dental hygienists wind up in this situation because they are unsure of the current AP guidelines.

Uncertainty regarding AP guidelines results in many patients continuing to premedicate when it is unnecessary. A cohort study of dental visits between 2011 and 2015 found that 80.9% of AP prescriptions were unnecessary.1 Additionally, only 20.9% of patients had a cardiac condition at the highest risk of adverse outcomes from infective endocarditis, which would warrant AP prior to dental procedures. The study also found that despite changes in clinical guidelines, AP prescribing has remained steady among dentists.1

Related reading:

- Joint replacements and antibiotic prophylaxis: Is it really necessary?

- New AHA guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis

Antibiotic resistance and adverse reactions

Inappropriate use of antibiotics is a growing concern worldwide because it can result in antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance means the bacteria no longer responds to antibiotics. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that antibiotic-resistant infections cause 23,000 deaths and two million infections annually in the US.2

In addition to antibiotic resistance, antibiotics are a major cause of adverse effects. A 2018 study found more than 145,000 emergency hospital visits for systemically administered antibiotic adverse events in adults between 2011 and 2015, and approximately 75% of the cases involved allergic reactions to antibiotics.2 Examples of adverse effects from antibiotics include anaphylaxis, rash, diarrhea, Clostridium difficile, nausea, gastric pain, and fever.

Antibiotic stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship encompasses the steps taken by health-care professionals to ensure responsible prescribing and use of antibiotics. Improving antibiotic prescribing in the dental office helps to reduce adverse reactions and antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic stewardship is essential to maintain our ability to manage life-threatening infections, by ensuring that antibiotics are used only in situations in which they are necessary and effective.3 A dental professional’s role in antibiotic stewardship begins by adhering to current guidelines.

American Heart Association guidelines

In 2007, the American Heart Association (AHA) updated AP guidelines for the prevention of viridans group streptococcal (VGS) infective endocarditis (IE). Compared with previous recommendations, the guidelines significantly reduced the number of patients for whom AP is indicated. Rather than identify the risk of acquisition of VGS IE, the new guidelines identified the highest risk of adverse outcomes from complications of VGS IE. In May 2021, the AHA released a scientific statement that reaffirms the 2007 recommendations on the prevention of VGS IE:

“On the basis of a review of the available evidence, there are no recommended changes to the 2007 VGS IE prevention guidelines. We continue to recommend VGS IE prophylaxis only for categories of patients at highest risk for adverse outcome while emphasizing the critical role of good oral health and regular access to dental care for all.” 3

The AHA continues to recommend AP to prevent VGS IE for the following patients who are at the greatest risk of posttreatment bacterial-related complications:

Group 1

- Prosthetic cardiac valve

- Prosthetic material used for valve repair

- Implantable cardiac devices such as a transcatheter aortic valve

Group 2

- Previous, relapse, or recurrent IE

Group 3

- Congenital heart disease

- Unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease, including palliative shunts and conduits

- Any repaired congenital heart defect with residual shunts or valvular regurgitation at the site of or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or a prosthetic device

Group 4

- Cardiac transplant recipient with valve regurgitation due to a structurally abnormal valve

Infective endocarditis and prosthetic joint infection

In general, AP is not recommended prior to dental procedures for patients with prosthetic joints. A systematic review conducted by the 2014 ADA Council on Scientific Affairs concluded that best evidence fails to show a link between prosthetic joint infection (PJI) and dental procedures.4 According to the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS), moderate strength evidence finds that dental procedures are unrelated to implant infection, and AP prior to dental procedures does not reduce the risk of subsequent implant infection.5 Additionally, for most patients, the risks of adverse reactions and antibiotic resistance generally outweigh the benefit of AP. Therefore, the ADA and AAOS no longer recommend that all individuals with prosthetic joints take AP prior to dental treatment.4,5

Special considerations that may indicate AP for patients with prosthetic joints:

- If the patient has a history of a previous medical condition(s) or,

- If the patient had a complication(s) associated with the joint replacement surgery

In cases where AP is deemed necessary, it is recommended that the orthopedic surgeon write the prescription.6

Clindamycin no longer recommended

The 2021 AHA scientific statement no longer recommends the use of clindamycin for patients who are allergic to penicillin or ampicillin. This is becauseSpecial considerations

- If the patient inadvertently forgets to take their AP, the dosage may be taken up to two hours after the procedure.2

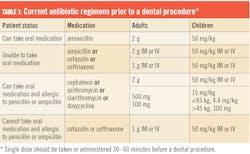

- In patients who are receiving a short course (7–10 days) of oral antibiotic therapy, it is preferable to select a different class of antibiotic before a dental procedure (table 1).

- If possible, it is preferable to delay an elective dental procedure for at least 10 days after completion of a short course of antibiotic therapy.3

- In patients who are receiving parenteral antimicrobial therapy for IE or other infections and require a dental procedure, the same parenteral antibiotic may be continued through the dental procedure.3

- In patients undergoing multiple sequential dental appointments, if possible, it is preferable to delay the next procedure for four weeks between treatment sessions.3

The importance of good oral health to prevent VGS IE

The 2021 AHA scientific statement emphasizes the critical role of good oral health, because VGS IE is more likely to be caused by transient bacteria from daily activities than a dental procedure. Daily activities such as brushing and flossing result in a higher frequency of bacteremia than a dental procedure. For example, there is a 20%–68% chance of bacteremia from brushing or flossing versus a 40% chance from a dental cleaning.7 Therefore it is imperative that dental hygienists educate patients about good oral health practices that include brushing, interdental cleaning, and routine hygiene appointments. If insurance or affordability are a barrier to routine care, the dental team can guide the patient to resources that will provide access—i.e., a local dental hygiene school or federally qualified health center (FQHC).

Steps dental hygienists can take toward antibiotic stewardship

- During review of the patient’s medical history, discuss their risk for VGS IE and educate them on current AHA recommendations.

- Educate on the risks versus benefits of AP (i.e., adverse reactions and antibiotic resistance).

- Recommend a discussion with both the dentist and physician to determine if AP should be discontinued.

- Inform the patient when the current medication they are taking for AP is no longer recommended, and then refer to the prescribing doctor for a medication change.

- Provide home-care education, emphasizing the importance of good oral health to prevent VGS IE.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the January 2022 print edition of RDH.

References

- Suda KJ, Calip GS, Zhou J, et al. Assessment of the appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions for infection prophylaxis before dental procedures, 2011 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193909. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3909

- Antibiotic stewardship. American Dental Association. Updated September 29, 2020. https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-stewardship

- Wilson WR, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, et al. Prevention of viridans group streptococcal infective endocarditis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(20):e963-e978. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000969

- Sollecito TP, Abt E, Lockhart PB, et al. The use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints: evidence-based clinical practice guideline for dental practitioners—a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(1):11-16.e8. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2014.11.012

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons/American Dental Association. Prevention of Orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures evidence-based clinical practice guideline. December 12, 2012. https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/dental/pudp_guideline.pdf

- Management of patients with prosthetic joints undergoing dental procedures. Chairside guide for prosthetics. American Dental Association. 2015. https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_chairside_guide_prosthetics.pdf

- Usmani S, Choquette L, Bona R, Feinn R, Shahid Z, Lalla RV. Transient bacteremia induced by dental cleaning is not associated with infection of central venous catheters in patients with cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(4):286-294. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2017.12.022