Differential diagnosis for periodontal pathologies for nonplaque-induced gingival diseases (NPIGD)

The new classification sheds light on the intricate landscape of NPIGD, encompassing a broad spectrum of underlying causes. These range from genetic predispositions and systemic disorders to specific infections and localized reactive processes. Each category presents with characteristic clinical manifestations, such as erythema, edema, pain, bleeding, and altered gingival contours, though the underlying pathogenesis often involves a complex interplay of factors.

Current research suggests a multifactorial cascade in nonplaque-related gingivitis, where an initial insult—such as a systemic condition or immune dysregulation—will trigger and damage the gingival tissues and set off a localized inflammatory response, marked by the influx of immune cells and the release of inflammatory mediators. If left untreated, the chronic inflammation can escalate into irreversible destruction of both gingival and bone structures.

Therapeutic intervention for NPIGD needs to go hand in hand with a comprehensive approach that addresses the root cause, extending beyond traditional plaque control measures. Antimicrobial therapy, immunomodulation, or targeted treatment for underlying systemic conditions plays a crucial role in the treatment of NPIGD. By understanding and utilizing this new system, clinicians can unlock a deeper understanding of NPIGD, paving the way for personalized treatment plans and improved patient outcomes.

Etiology of NPIGD

Let’s dig deeper into the etiological factors of NPIGD.

Genetic conditions

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (HGF) is a rare genetic condition characterized by abnormal overgrowth of gum tissue, varying in severity and potentially affecting both the upper and lower jaws. This overgrowth can occur independently or as part of a syndrome, sometimes linked to other health issues such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, or other genetic syndromes.2

HGF is caused by gene mutations that control connective tissue growth and is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Its symptoms typically emerge during childhood or adolescence, coinciding with the transition to permanent dentition. Common signs include:

- Dotted or speckled pink gums

- Extensive gingival overgrowth that may cover teeth

- Firm, nonbleeding gum tissue

This excessive growth could impede tooth eruption and negatively impact self-esteem in affected individuals. Treatment often involves surgical removal of the excess gum tissue to improve function and esthetics. However, due to the genetic nature of HGF, recurrence is common, necessitating maintenance and potential repeat procedures.3

Specific infections

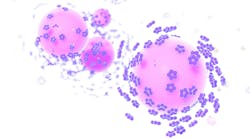

Necrotizing periodontal diseases (NPDs) are a group of severe infections characterized by rapid tissue destruction, pain, ulcerations, and necrosis, distinguishing them from more common forms of gingivitis. The classification of NPDs encompass a spectrum of severity, ranging from localized necrotizing gingivitis (NG) to more extensive necrotizing periodontitis (NP), and, in extreme cases, necrotizing stomatitis (NS) and noma.

While the precise etiology of NPDs remains unknown, they are considered polymicrobial infections, where a synergistic interplay of bacteria, viruses, and fungi contributes to their pathogenesis. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Fusobacterium nucleatum are frequently implicated in producing toxins capable of inflicting substantial damage to the periodontum.4 However, the role of these microorganisms is complex. Whether they are the primary causative agents or merely opportunistic pathogens thriving in a compromised environment is unclear, but evidence suggests that host factors play a significant role. Individuals with weakened immune systems, malnutrition, tobacco use, or stress are more susceptible to NPDs, indicating that preexisting conditions create a conducive environment for these infections to flourish.

The nontransmissible nature of NPDs reinforces the importance of host factors, where these infections likely arise from shifts in the oral microbiome triggered by underlying predispositions, leading to a dysbiotic state favoring pathogenic microbes.5,6

Notably, other bacterial infections (e.g., gonorrhea, tuberculosis,7 and syphilis), viral infections (e.g., herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster), and fungal infections (e.g., candidiasis and histoplasmosis) are included in this category. These infections can manifest with diverse clinical presentations ranging from ulcerations and erythema to tissue necrosis, often requiring specialized diagnostic techniques such as cultures or biopsies for confirmation. This recognition facilitates targeted treatment strategies and emphasizes the need for interdisciplinary collaboration in managing these complex cases.

Inflammatory and immune conditions

Conditions associated with immune system dysregulation can lead to gingival inflammation without the typical bacterial biofilm accumulation. Hypersensitivity reactions, such as contact allergy to dental materials or oral hygiene products, can manifest as localized or generalized gingivitis.8,9 Autoimmune disorders, such as pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid, and systemic lupus erythematosus, can also affect the gingiva, causing inflammation, blistering, and ulceration. Granulomatous conditions such as sarcoidosis or Crohn’s disease may also present with gingival involvement.

Diagnosing these conditions requires a multidisciplinary approach, including a detailed medical history, clinical examination, and, potentially, laboratory tests and biopsies. Treatment strategies vary depending on the underlying cause and may involve topical or systemic medications, allergen avoidance, and collaboration with medical specialists.10,11

Reactive processes

Irritants can range from faulty restorations and ill-fitting prostheses to fractured teeth and orthodontic appliances. The resulting lesions typically emerge from the gingival sulcus, displacing the gingival margin. Common examples include fibrous hyperplasia (fibrous epulis), pyogenic granuloma, and peripheral giant cell granuloma. These lesions can vary in appearance, from firm pink overgrowths to vascular, ulcerated masses. Accurate diagnosis often requires identifying and addressing the underlying irritant, as failure can lead to lesion recurrence.12,13

Neoplastic disorders

Premalignant conditions such as leukoplakia and erythroplakia can precede the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), the most common malignant neoplasm affecting the gingiva. While not all lesions progress to cancer, their early detection is crucial. The NPIGD classification emphasizes the importance of vigilant oral examinations, recognizing suspicious lesions, and prompt biopsies to identify dysplasia or early malignancy, allowing for timely intervention and improved patient prognosis.14

Malignant neoplasms, including squamous cell carcinoma or lymphoma, pose a more significant threat due to their invasive potential and require prompt diagnosis and intervention.15 While the exact etiology of these neoplasms remains unclear, potential contributing factors include genetic predispositions, chronic irritation, viral infections, and immune system dysregulation. A thorough clinical examination, supplemented with biopsy and histopathological analysis, is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.16,17

Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases

These systemic conditions can manifest in oral tissues, leading to gingival inflammation and enlargement independent of plaque accumulation. Vitamin C deficiencies (scurvy) can cause gingival bleeding and ulceration. Additionally, hormonal imbalances, as seen in diabetes mellitus, can predispose individuals to exaggerated gingival inflammation, and metabolic bone diseases, such as Paget’s disease, may also contribute to nonplaque-induced gingival changes.18

Traumatic lesions (physical, mechanical, chemical, and thermal insults)

Traumatic lesions arise from physical or chemical injury to gingival tissues, independent of plaque accumulation. Examples include frictional keratosis caused by chronic irritation, chemical burns from misuse of oral hygiene products, and physical trauma from accidental biting or aggressive toothbrushing. Recognizing traumatic lesions is crucial for proper diagnosis and treatment, which involves addressing the source of trauma and promoting healing.

Gingival pigmentations

This encompasses endogenous pigmentation (e.g., pigmented nevus, smoker’s melanosis) and exogenous pigmentation (e.g., amalgam tattoo). While these pigmentations do not directly cause gingivitis, they can be critical clinical findings in diagnosing and managing NPIGD.19

Importance of differential diagnosis: A decision tree approach

A systematic approach, such as a decision tree, provides a valuable road map:

- Location: Is the enlargement localized or generalized? This initial question helps distinguish between conditions that affect specific areas of the gums versus those that are widespread.

- Systemic symptoms: Are there accompanying fever, fatigue, or other issues?

- History: Is there a history of trauma or irritation?

- Visual cues: Are there distinct color or texture changes in the gums?

The role of dental hygienists

We are often the first line of defense in identifying and managing nonplaque-induced gingival conditions. Our ability to recognize subtle clinical signs, gather a thorough patient history, and educate patients on oral hygiene is essential.20 Early detection and appropriate referral to a periodontist can significantly improve treatment outcomes and prevent complications.

Even though nonplaque-induced gingival enlargements present a unique challenge for dental professionals, if we master a systematic approach to differential diagnosis and stay current with the latest research, we can confidently navigate these complexities and provide optimal patient care.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the August/September 2024 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Holmstrup P, Plemons J, Meyle J. Non-plaque-induced gingival diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S28-S43. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12938

- Almiñana-Pastor PJ, Buitrago-Vera PJ, Alpiste-Illueca FM, Catalá-Pizarro M. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: characteristics and treatment approach. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(4):e599-e602. doi:10.4317/jced.53644

- Ramer M, Marrone J, Stahl B, Burakoff R. Hereditary gingival fibromatosis: identification, treatment, control. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127(4):493-495. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0242

- Tkacz K, Gill J, McLernon M. Necrotising periodontal diseases and alcohol misuse – a cause of osteonecrosis? Br Dent J. 2021;231(4):225-231. doi:10.1038/s41415-021-3272-9

- Blair FM, Chapple ILC. Prescribing for periodontal disease. Prim Dent J. 2014;3(4):38-43. doi:10.1308/205016814813877234

- Kara C, Gökmenoglu C, Sahin O, Cinel S, Kara NB, Sadik E. A new management strategy for the treatment of streptococcal gingivitis: a pilot study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(2):235-239.

- Jain S, Vipin B, Khurana P. Gingival tuberculosis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2009;13(2):106-108. doi:10.4103/0972-124X.55836

- Torgerson RR, Davis MDP, Bruce AJ, Farmer SA, Rogers RS 3rd. Contact allergy in oral disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2):315-321. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.04.017

- Tsushima F, Sakurai J, Shimizu R, Kayamori K, Harada H. Oral lichenoid contact lesions related to dental metal allergy may resolve after allergen removal. J Dent Sci. 2022;17(3):1300-1306. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2021.11.008

- Garcia-Pola MJ, Rodriguez-López S, Fernánz-Vigil A, Bagán L, Garcia-Martín JM. Oral hygiene instructions and professional control as part of the treatment of desquamative gingivitis. Systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(2):e136-e144. doi:10.4317/medoral.22782

- Ohta M, Osawa S, Endo H, Kuyama K, Yamamoto H, Ito T. Pemphigus vulgaris confined to the gingiva: a case report. Int J Dent. 2011;2011:207153. doi:10.1155/2011/207153

- Brierley DJ, Crane H, Hunter KD. Lumps and bumps of the gingiva: a pathological miscellany. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(1):103-113. doi:10.1007/s12105-019-01000-w

- Sarwal P, Lapumnuaypol K. Pyogenic Granuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556077/

- Bandara DL, Jayasooriya PR, Jayasinghe RD. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia of the gingiva: an early lesion refractory to surgical excision. Case Rep Dent. 2019;2019:5785060. doi:10.1155/2019/5785060

- Yasumoto M, Shibuya H, Fukuda H, Takeda M, Mukai T, Korenaga T. Malignant lymphoma of the gingiva: MR evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(4):723-727.

- Sapna N, Vandana KL. Idiopathic linear leukoplakia of gingiva: a rare case report. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14(3):198-200. doi:10.4103/0972-124X.75918

- Ohta K, Yoshimura H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva. Am J Med Sci. 2022;363(1):e3. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2021.05.024

- Japatti SR, Bhatsange A, Reddy M, Chidambar YS, Patil S, Vhanmane P. Scurvy-scorbutic siderosis of gingiva: a diagnostic challenge – a rare case report. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2013;10(3):394-400.

- Singh G, Preethi B, Chaitanya KK, Navyasree M, Kumar TG, Kaushik MS. Prevalence of oral mucosal lesions among tobacco consumers: cross-sectional study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2023;15(Suppl 1):S562-S565. doi:10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_104_23

- Zhao H, Zhang S, Ma J, Sun X. Impact of oral hygiene on prognosis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lower gingiva. Front Surg. 2021;8:711986. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2021.711986

About the Author

Andreina Sucre, MSc, RDH

Andreina Sucre, MSc, RDH, is an international dentist, oral pathology, and oral surgery specialist practicing dental hygiene in Miami, Florida. A passionate advocate for early pathological diagnosis, she empowers colleagues through lectures focused on oral pathologies. Andreina spoke on this topic at the 2024 ADHA Annual Conference, 2023 RDH Under One Roof, and she writes about oral pathology for RDH magazine. Committed to community outreach, she educates non-native English-speaking children on oral health and actively volunteers in dental initiatives.