Erosive lichen planus vs. erythematous candidiasis: How to spot the difference

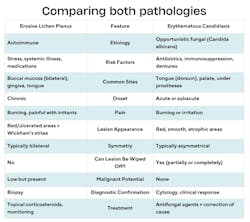

Recognizing the subtle differences between look-alike conditions is vital for accurate referral and diagnosis. Two red lesions—erosive lichen planus (OLP) and erythematous candidiasis—can appear deceptively similar. But they have fundamentally different origins, implications, and management approaches (figure 1).1

Clinical presentation: Distinguishing features

When evaluating red lesions in the oral cavity, OLP and erythematous candidiasis are frequently considered in the differential diagnosis due to their overlapping clinical features. However, subtle distinctions in appearance, distribution, and associated features can guide accurate diagnosis.

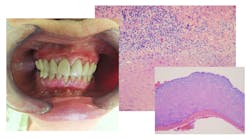

Erosive lichen planus typically presents as well-demarcated erythematous or ulcerative lesions, often accompanied by Wickham’s striae—a network of fine, white, lace-like lines on its reticular type. These lesions most often affect the bilateral buccal mucosa but can also involve the gingiva (as desquamative gingivitis), tongue, and labial mucosa. Patients frequently report pain, especially during eating or when exposed to spicy or acidic foods.

In contrast, erythematous candidiasis appears as diffuse, red, atrophic areas and gives a burning sensation. The affected area may appear smooth and thinned, especially on the cases affecting the dorsum of the tongue, palate, and buccal mucosa. Lesions are typically asymmetrical and may correlate with local risk factors such as denture coverage, antibiotic use, or immunosuppression. Unlike OLP, candidiasis rarely presents with white striae or ulceration.2

Who is at risk?

OLP is an autoimmune mucocutaneous disorder. Its etiology is multifactorial and associated with chronic inflammation, stress, systemic diseases, and certain medications. It predominantly affects middle-aged women and follows a chronic, relapsing course.3 Though benign, the erosive form carries a small but significant risk of malignant transformation, making long-term monitoring essential.4

Erythematous candidiasis, in contrast, is an opportunistic fungal infection caused by Candida albicans. It is often secondary to immunosuppression, xerostomia, poorly controlled diabetes, antibiotic therapy, or ill-fitting prosthetics. While not premalignant, candidiasis may signal an underlying systemic imbalance.5

Symptoms that differentiate the two conditions

While both conditions can present with white or red patches, their symptoms provide important clues. Lichen planus, particularly the reticular form, is often asymptomatic, but the erosive type can cause burning pain, sensitivity to spicy foods, and discomfort when eating. Patients often report that the lesions have persisted for months or years, reflecting their chronic nature.6

Candidiasis, on the other hand, tends to develop more suddenly and frequently causes a burning sensation or discomfort, especially in erythematous cases. A key distinguishing feature is that candidiasis lesions can be wiped away, whereas lichen planus remains firmly attached to the mucosa. Patients with candidiasis may also have angular cheilitis, particularly if they wear dentures or experience salivary gland hypofunction.7

How to confirm the diagnosis

A biopsy is often recommended for lichen planus, especially in cases of erosive or ulcerative lesions, to rule out dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma. Unlike candidiasis, there are no fungal elements present under the microscope. Candidiasis is often a clinical diagnosis and can be confirmed with a simple cytology smear that reveals fungal hyphae.

Treatment and management

Since lichen planus has no cure, management focuses on symptom relief and monitoring. Reticular, asymptomatic cases may not require treatment, but painful or erosive lesions often benefit from topical corticosteroids such as dexamethasone rinses. Patients should be educated on the importance of long-term monitoring as chronic inflammation has been linked to a low but significant risk of malignant transformation.8

Candidiasis requires antifungal therapy. Topical treatments such as nystatin or clotrimazole troches are commonly used, but systemic antifungals like fluconazole may be necessary for persistent or widespread cases. Addressing the underlying cause, whether it’s poorly controlled diabetes, medication-induced xerostomia, or ill-fitting dentures, is essential to prevent recurrence.9

Key takeaways for dental pros

Distinguishing between these two conditions hinges on clinical vigilance.

- Does the lesion wipe off?

- Is it bilateral or asymmetrical?

- Are Wickham’s striae present?

- Is the pain chronic or acute?

The answers guide your documentation and the urgency of your referrals. A detailed chart entry that describes size, color, borders, surface texture, location, and associated symptoms will empower the entire dental team.10 When in doubt, biopsy or refer. Early detection can significantly alter patient outcomes.

References

1. Diebold S, Overbeck M. Soft tissue disorders of the mouth. Emer Med Clins N Amer. 2019;37(1):55-68. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.006

2. Hellstein JW, Marek CL. Candidiasis: red and white manifestations in the oral cavity. Head Neck Path. 2019;13(1):25-32. doi:10.1007/s12105-019-01004-6

3. Zhou X, Cai X, Tang Q, et al. Differences in the landscape of colonized microorganisms in different oral potentially malignant disorders and squamous cell carcinoma: a multi-group comparative study. BMC Microb. 2024;24(1):318. doi:10.1186/s12866-024-03458-3

4. Netto JNS, Pires FR, Costa KHA, Fischer RG. Clinical features of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: an oral pathologist's perspective. Brazil Dent J. 2022;33(3):67-73. doi:10.1590/0103-6440202204426

5. Tahmasebi E, Keshvad A, Alam M, et al. Current infections of the orofacial region: treatment, diagnosis, and epidemiology. Life (Basel, Switzerland), 2023;13(2):269. doi:10.3390/life13020269

6. Fitzpatrick SG, Hirsch SA, Gordon SC. The malignant transformation of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a systematic review. JADA. 2014;145(1):45-56. doi:10.14219/jada.2013.10

7. Millsop JW, Fazel N. Oral candidiasis. Clins Derm. 2016;34(4):487-494. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.022

8. Belkacem Chebil R, Oueslati Y, Marzouk M, Ben Fredj F, Oualha L, Douki N. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid lesions in Sjogren's syndrome patients: a prospective study. Int J Dent. 2019:1603657. doi:10.1155/2019/1603657

9. Contaldo M, Di Stasio D, Romano A, et al. Oral candidiasis and novel therapeutic strategies: antifungals, phytotherapy, probiotics, and photodynamic therapy. Current Drug Deliv. 2023:20(5):441-456. doi:10.2174/1567201819666220418104042

10. Sucre A. The importance of properly recording oral pathologies for dental hygienists. RDH mag. October 30, 2024. https://www.rdhmag.com/pathology/oral-pathology/article/55239158/the-importance-of-properly-recording-oral-pathologies-for-dental-hygienists

About the Author

Andreina Sucre, MSc, RDH

Andreina Sucre, MSc, RDH, is an international dentist, oral pathology, and oral surgery specialist practicing dental hygiene in Miami, Florida. A passionate advocate for early pathological diagnosis, she empowers colleagues through lectures focused on oral pathologies. Andreina spoke on this topic at the 2024 ADHA Annual Conference, 2023 RDH Under One Roof, and she writes about oral pathology for RDH magazine. Committed to community outreach, she educates non-native English-speaking children on oral health and actively volunteers in dental initiatives.