The role of dental hygienists in identifying and treating airway dysfunction

Dental hygienists play a crucial role as first responders in identifying airway dysfunction. Their unique role in preventive dentistry is paramount, as they not only provide preventive care that mitigates the risk of oral and systemic diseases, but they correct and restore the natural function of orofacial structures.

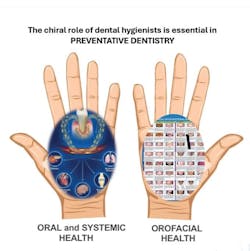

I like to say we have a “chiral role” in preventive dentistry. Like hands, orofacial health and oral and systemic health are asymmetric and mirror one another, and dental hygienists play a major role in this (figure 1).

Dental hygiene focuses on developing and implementing oral health management strategies to prevent oral and systemic diseases and ensure continuing care. Dental hygienists play a vital and unique role in this field, especially when it comes to addressing malocclusion rates. With the growing interest in orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) and dental sleep medicine as a modality that dental hygienists can offer, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) has maintained a clear policy on OMT since 2020.

“The ADHA recognizes and supports registered dental hygienists who have received education in orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT). These dental hygienists can provide orofacial myofunctional assessments and treatment independently in various practice settings and for patients of all ages.”

The role of the RDH in malocclusion

Crooked teeth and malocclusion are signs of insufficient jaw size and poor facial and airway development.1 Considering that patients visit a dental office more often than a medical office, hygienists can play a significant role in screening for common chronic diseases and breathing dysfunction.

If dental caries is a serious public health concern, malocclusion is just as serious. Left untreated, malocclusion can cause several health problems, such as sleep disordered breathing.2 Malocclusion and noisy sleep breathing in children can be addressed through proper screening, preliminary diagnosis, and appropriate referrals. Additionally, patients with medical conditions may present first at a dental visit during a recall appointment, and addressing these conditions is crucial to ensure timely care.

Oral health is an integral part of systemic health. Malocclusion significantly impacts oral health by increasing dental caries, periodontitis, risk for trauma, and difficulties in masticating, swallowing, breathing, and speaking.3 Dental hygienists can be the first to screen, recognize, and make appropriate referrals to address these issues. They can bridge the gap between dentistry and medicine, creating equitable oral health access and a more holistic approach to health care.4

Dr. Alfred Fones pioneered dental hygiene as a public health profession, emphasizing the importance of working collaboratively in a multidisciplinary team to prevent disease and promote health. In 2013, we celebrated the remarkable progress of dental hygiene. The ADHA adopted the theme, “100 years of dental hygiene: Proud past, unlimited future.” Dental hygiene is 112 years old.

Working with the upper airway

While the absence of oral diseases is a sign of good oral health, it’s not the sole indicator of overall well-being. Oral health encompasses a functional and structural state of well-being essential for optimal breathing, eating, and speaking. Many children and adults exhibit symptoms despite having no visible dental disease. A recent study revealed an association between severe malocclusion, daytime sleepiness, and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing in children and adults.5 The size of the pediatric airway is influenced by craniofacial and soft tissue structures.

Increases in upper airway resistance—including any combination of narrowing/retro-positioning of the maxilla/mandible or adeno-tonsillar hypertrophy—will predispose kids to OSA.6 The ADA has adopted a policy to redefine the dentist’s role in airway health for patients. If there’s a dental-craniofacial aspect to the diagnosis, dental hygienists who have education in the stomatognathic system are ideally positioned to assist patients with dental-related diagnosis.

We must evolve as providers and advocate for all. With a renewed focus on airway health and wellness, we must redefine our approach to patient care. A whole oral health-centered approach is essential. According to the Children’s Airway First Foundation, approximately 400 million children worldwide suffer from compromised airways in the United States, 11 million children under the age of 10 are affected, and 95% of these children remain undiagnosed.7

Furthermore, one in four adults have undiagnosed sleep apnea, and 57 studies have reported the prevalence of sleep disturbances in children and adolescents.7 Myofunctional therapy is rooted in dentistry,8 and dental hygienists' education and expertise uniquely positions us to play a vital role in the assessment and treatment of orofacial myofunctional disorders.

Grounded in evidence-based research, OMT demonstrates its value in effectively addressing and improving oral muscle and airway dysfunction in patients of all ages. Dr. Guilleminault et al. highlights the significant role of OMT in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing.9 A study from Stanford shows that myofunctional therapy reduces the apnea-hypopnea index by approximately 50% in adults and 62% in children,10 and improves oxygen saturations, snoring, and sleepiness in adults.

We need to embrace the unique role that dental hygienists play in preventive dentistry. Achieving optimal oral health is the foundation of our profession. We can provide care that promotes the prevention of oral and systemic diseases, and provide OMT that corrects and restores the natural function of the orofacial structures for healthy breathing. Dental hygiene is constantly evolving and moving forward in the right direction.

References

1. Kahn S, Ehrlich P, Feldman M, Sapolsky R, Wong S. The jaw epidemic: recognition, origins, cures, and prevention. Bioscience. 2020;70(9):759-771. doi:10.1093/biosci/biaa073.

2. Rao D, Avinash B, Raghunath N, Kudagi VS, Kumar SS, Oommen K. Sleep-disordered breathing – a dental perspective. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2022;14(Suppl 1):S1082-S1086. doi:10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_

3. Mtaya M, Brudvik P, Astrom AN, 2009. Prevalence of malocclusion and its relationship with socio-demographic factors, dental caries and oral hygiene in 12 to 14-year-old Tanzanian school children. Eur J Orthodont. 31:467–476.

4. Fellows JL, Atchison KA, Chaffin J, Chávez EM, Tinanoff N. Oral health in America: implications for dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2022;153(7):601-609. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2022.04.002

5. Shirke SR, Katre AN. Association of sleep-disordered breathing and developing malocclusion in children: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e39813. doi:10.7759/cureus.39813

6. Katz ES, D'Ambrosio CM. Pathophysiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):253-262. doi:10.1513/pats.200707-111MG

7. Cai H, Chen P, Jin Y, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiological surveys. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14(1):12. doi:10.1038/s41398-023-02654-5.

8. Rogers AP. Exercises for the development of the muscles of the face, with a view to increasing their functional activity. The Dental Cosmos. 1918;(59):857-924.

9. Guilleminault C, Huang YS, Monteyrol PJ, Sato R, Quo S, Lin CH. Critical role of myofascial reeducation in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2013;14(6):518-525. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2013.01.013

10. Camacho M, Certal V, Abdullatif J, Zaghi S, Ruoff CM, Capasso R, Kushida CA. Myofunctional therapy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2015;1;38(5):669-675. doi:10.5665/sleep.4652

About the Author

Nerissa Boggan, BSDH, RDH, Cert BBM, AOMT-C

Nerissa Boggan, BSDH, RDH, Cert BBM, AOMT-C, is a myofunctional therapist and sleep and breathing educator. She has worked in the dental hygiene field for more than 25 years. She recently published her first children’s book, highlighting the importance of nasal breathing and nasal hygiene. A passionate airway and sleep health advocate, she actively advocates about the importance of dental airway screening and patient education. Nerissa is the author of My Dog Myo and My Nose. For more information visit orofacialfitness.com.