The dangers of high fibrinogen levels

Oh, what a tangled systemic web we weave when subgingival microbes and host immune and inflammatory responses cleave. The relationship between oral health and whole-body health is complex, but thankfully research is becoming plentiful. An area well studied is the intersection between cardiovascular health and periodontal pathogens. However, what may not be as clear to clinicians is the association between heart health, oral health, and fibrinogen. Why does it matter?

What is fibrinogen?

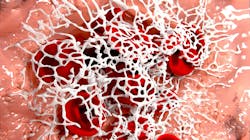

Fibrinogen is a protein in the blood and is a decision maker in platelet stickiness. Fibrinogen is a soluble plasma glycoprotein that is synthesized by the liver, converted into fibrin by thrombin during coagulation of blood.

Say, for instance, you cut your finger and it’s bleeding. Fibrinogen jumps in and stops the bleeding by forming a blood clot. That’s terrific, but there must be limits. Too much and you are a hot sticky mess, so to speak, with unnecessary clotting and a disruption in blood circulation. A normal healthy level is 200-400 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter).

Additional reading:

Cracking the code: 5 tips on periodontal maintenance procedures

High fibrinogen values could be related to cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, stroke, heart attack, infections, or inflammation. Diets high in iron, sugar, and caffeine along with obesity can raise levels.1 For pregnant women, the level may increase to 450 mg/dL, whereas nonpregnant women could have an average of 300 mg/dL. Could this be a preventive measure by our bodies to reduce excessive bleeding during childbirth?

High levels of fibrinogen are also related to brain atrophy and Alzheimer’s disease and can impact the initiation or progression of systemic disease processes such as atherosclerois.2-5 The Eurostroke project looked at levels of fibrinogen and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke. They found that fibrinogen is a “powerful predictor of stroke.” 6

Fibrinogen that is converted to fibrin contributes to vascular disease by damaging the endothelial cells of artery linings, stimulating the proliferation of vascular muscle cells and activating inflammatory cells. Elevated plasma fibrinogen levels are known to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease by increasing the chance of blood clots.7

Besides the role in blood clotting, fibrinogen can also increase inflammation in three ways: by forming the basis for the accumulation of inflammatory cells, advancing the immune response, and aiding in bacterial colonization, adhesion, and invasion.

Smokers commonly see fibrinogen increase.8 The relationship between the increase in plasma fibrinogen and smoking isn’t completely clear, but it could be related to the increased level of C-reactive protein (CRP), whose production is stimulated but interleukin-6 (IL-6). Oxidative stress happens as a response to smoking and the generation of IL-6 follows.

Fibrinogen and periodontal disease

Chronic gingivitis is extremely prevalent in the population as a whole. The acute phase response associated with gingival inflammation increases the production of CRP and fibrinogen.9,10 In periodontitis, not only are CRP and fibrinogen elevated; so are glucose and IL-18.11 In an exploration of chronic aggressive periodontitis patients as compared to healthy controls, research found serum CRP and fibrinogen are increased.12

The great news is serum levels for CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-6 are decreased following periodontal therapy.13-15 In the event that extractions are needed for patients with advanced periodontal disease, that treatment may lower cardiovascular risk and lower fibrinogen, as well.16

There are other opportunities we can share to help patients lower their fibrinogen levels. We can recommend omega-3 fatty acids because fish oil helps reduce heart attack risk. It can also reduce triglycerides, suppress inflammation, and can protect against arrhythmia.17 Adding omega-3s to post-op instructions following periodontal therapy may be a bonus.

Niacin may also be of use. Niacin reduces production of fibrinogen by the liver and can raise HDL cholesterol (the good stuff).18 Niacin does have a few unpleasant side effects such as stomach upset, skin rash, or flushing. Always consult with the patient’s physician. Many of us take vitamin C as a supplement, and it can help break down fibrinogen and lower cholesterol.19,20 Vitamin C supplementation of 2,000 mg/day can increase fibrinogen breakdown by 45%.21

We can make a difference by treating patients’ periodontal disease and reducing their risk of cardiovascular disease. Cardiac patients, smokers, and patients with hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, or obesity already have confounding factors of concern. When formulating a treatment plan, we must critically assess medical histories and evaluate periodontal health status to do what is in the best health interest of the patient.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the September 2022 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Miura K, Nakagawa H, Ueshima H, et al. Dietary factors related to higher plasma fibrinogen levels of Japanese-Americans in Hawaii compared with Japanese in Japan. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(7):1674-1679. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000225701.20965.b9

- Ahn HJ, Glickman JF, Poon KL, et al. A novel Aβ-fibrinogen interaction inhibitor rescues altered thrombosis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Exp Med. 2014;211(6):1049-1062. doi:10.1084/jem.20131751

- Tampubolon G. Repeated systemic inflammation was associated with cognitive deficits in older Britons. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2015;3:1-6. doi:10.1016/j.dadm.2015.11.009

- Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279(18):1477-1482. doi:10.1001/jama.279.18.1477

- Ridker PM, Buring JE, Shih J, Matias M, Hennekens CH. Prospective study of C-reactive protein and the risk of future cardiovascular events among apparently healthy women. Circulation. 1998;98(8):731-733. doi:10.1161/01.cir.98.8.731

- Bots ML, Elwood PC, Salonen JT, et al. Level of fibrinogen and risk of fatal and non-fatal stroke. EUROSTROKE: a collaborative study among research centres in Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i14-i18. doi:10.1136/jech.56.suppl_1.i14

- Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration, Danesh J, Lewington S, et al. Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis [published correction appears in J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(22):2848]. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(14):1799-1809. doi:10.1001/jama.294.14.1799

- Tuut M, Hense HW. Smoking, other risk factors and fibrinogen levels. Evidence of effect modification. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(4):232-238. doi:10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00226-x

- Ebersole JL, Machen RL, Steffen MJ, Willmann DE. Systemic acute-phase reactants, C-reactive protein and haptoglobin, in adult periodontitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107(2):347-352. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.1997.270-ce1162.x

- Loos BG, Craandijk J, Hoek FJ, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van der Velden U. Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2000;71(10):1528-1534. doi:10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1528

- Buhlin K, Hultin M, Norderyd O, et al. Risk factors for atherosclerosis in cases with severe periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(7):541-549. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01430.x

- Chandy S, Joseph K, Sankaranarayanan A, et al. Evaluation of C-reactive protein and fibrinogen in patients with chronic and aggressive periodontitis: a clinico-biochemical study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):ZC41-ZC45. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/23100.9552

- Iwamoto Y, Nishimura F, Soga Y, et al. Antimicrobial periodontal treatment decreases serum C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not adiponectin levels in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74(8):1231-1236. doi:10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1231

- D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Andreou G, Brett PM, Ready D, Tonetti MS. Periodontitis and atherogenesis: causal association or simple coincidence? J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(5):402-411. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00580.x

- Montebugnoli L, Servidio D, Miaton RA, et al. Periodontal health improves systemic inflammatory and haemostatic status in subjects with coronary heart disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(2):188-192. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00641.x

- Taylor BA, Tofler GH, Carey HM, et al. Full-mouth tooth extraction lowers systemic inflammatory and thrombotic markers of cardiovascular risk. J Dent Res. 2006;85(1):74-78. doi:10.1177/154405910608500113

- Vanschoonbeek K, Feijge MA, Paquay M, et al. Variable hypocoagulant effect of fish oil intake in humans: modulation of fibrinogen level and thrombin generation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(9):1734-1740. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000137119.28893.0b

- Johansson JO, Egberg N, Asplund-Carlson A, Carlson LA. Nicotinic acid treatment shifts the fibrinolytic balance favourably and decreases plasma fibrinogen in hypertriglyceridaemic men. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1997;4(3):165-171. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9475670/

- Khaw KT, Woodhouse P. Interrelation of vitamin C, infection, haemostatic factors, and cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 1995;310(6994):1559-1563. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6994.1559

- Bordia AK. The effect of vitamin C on blood lipids, fibrinolytic activity and platelet adhesiveness in patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 1980;35(2):181-187. doi:10.1016/0021-9150(80)90083-0

- Tofler GH, Stec JJ, Stubbe I, et al. The effect of vitamin C supplementation on coagulability and lipid levels in

About the Author

Anne O. Rice, BS, RDH, CDP, FAAOSH

Anne O. Rice, BS, RDH, CDP, FAAOSH, founded Oral Systemic Seminars after over 35 years of clinical practice and is passionate about educating the community on modifiable risk factors for dementia and their relationship to dentistry. She is a certified dementia practitioner, a longevity specialist, a fellow with AAOSH, and has consulted for Weill Cornell Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic, FAU, and Atria Institute. Reach out to Anne at anneorice.com.