Patients with cardiovascular disease

Laura J. Webb, RDH, MS, CDA

Tips for providing low-risk pain control

to patients with complex medical conditions

National data indicates that our population is aging and, as medical science advances, we are seeing many more patients with complex medical conditions, including patients with cardiovascular diseases.

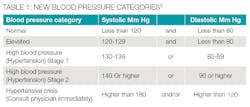

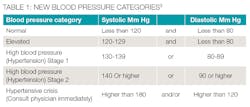

According to 2017 data from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, approximately 92.1 million American adults are living with some form of cardiovascular disease or the after-effects of stroke.1 Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death for men and women in the United States.2 Recently, and for the first time in 14 years, the blood pressure category guidelines were changed (see Table 1).3 So, it continues to be our ethical responsibility to remain updated with current literature and protocols, including a careful review the patient’s medical history and taking vital signs to assess the patient’s ability to tolerate care. A medical consultation with the patient’s physician may be advised in some circumstances.

All patients with cardiovascular disease require excellent pain control to avoid the release of endogenous epinephrine in response to stress from pain or anxiety.4 Controlling stress and anxiety is a major priority for risk reduction when treating patients with cardiovascular disease.

In most states, dental hygienists have several options for controlling pain and anxiety available to them:

• Blocking the conduction of pain impulses with the use of local and topical anesthesia to affect pain perception

• Raising the pain threshold and lowering anxiety through the use of nitrous-oxide and oxygen (N2O-O2) analgesia

• Psychosedation that can include a variety of nonpharmacological techniques (iatrosedation) to affect pain perception and pain reaction such as building trust and rapport, and utilizing relaxation, and distraction techniques.5

Patients with cardiovascular disease benefit greatly from stress reduction protocols that include:

• Short morning appointments

• A calm, quiet professional environment

• Open, honest communication about fears/concerns

• Preoperative sedation with a short-acting benzodiazepine, if needed

• Use of N2O-O2 analgesia

• Excellent pain control and patient contact the evening of procedure6,7

The use of N2O-O2 analgesia can be particularly advantageous for these patients because not only does it reduce anxiety and raise the pain threshold (facilitating safety during local anesthesia), but it provides oxygen enrichment.7

Local Anesthesia

Dental local anesthetics usually produce minimal effects on the cardiovascular system (CVS) when provided at non-overdose levels. For example, there may be a slight increase or no increase in blood pressure. However, at higher blood levels, there may be first observed a stimulation phase with increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration. Then, as the blood levels increase, a depression phase with reduced heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration follows, which may culminate in circulatory collapse and cardiac arrest.4,9

Dr. Stanley Malamed has stated, “Local anesthetics are the safest and most effective drugs available in all of medicine for the prevention and management of pain.”9 Although local anesthetics are exceptionally safe at therapeutic doses, we must consider existing conditions that may be intensified by the anesthetic agent and medications that may induce adverse interactions with local anesthetic agents. Selecting the appropriate agent, dose, and injection technique should be customized for each patient.

There are few absolute contraindications for specific local anesthetic agents for patients already eligible for elective procedures such as nonsurgical periodontal therapy (NSPT).

Plain local anesthetics are vasodilators, and when they are used, there is an increased rate of anesthetic absorption into the bloodstream, an increased risk of systemic toxicity, a reduction of duration of action, and an increased bleeding in the area .4,7,9 Vasoconstrictors (VC) are added to local anesthetic agents to counteract the vasodilatory properties. By constricting the blood vessels in the area, absorption is decreased, resulting in reduced risk of systemic toxicity, increased duration of action, and increased hemostasis. To promote safety and efficacy when providing local anesthesia, agents containing vasoconstrictors should be used unless there is an imperative reason or absolute contraindication not to use them. 9

Generally, absolute contraindications to receiving local anesthetic (with or without a vasoconstrictors) for patients with cardiovascular diseases are related to medically unstable conditions posing risk to patient safety. The following are absolute contraindications:

• Recent

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Coronary bypass surgery

- Cerebral Vascular Accident (stroke)

• Uncontrolled:

- Hypertension

- Angina

- Arrhythmias

- Other severe cardiac disease

• True allergy to sodium bisulfite

Note that, other than the true sodium bisulfite allergy, these conditions also contraindicate elective dental procedures such as NSPT.

All dental local anesthetic cartridges with vasoconstrictors contain bisulfite preservatives. Bisulfites are also commonly found in food and beverages. According to the FDA, hypersensitivity to bisulfites has been reported for approximately 1% of general population, and particularly with asthmatics (< 10% of asthmatics).4 Patients who have demonstrated a true allergy to bisulfites should not receive a local anesthetic agent containing vasoconstrictors.7,9 4% prilocaine plain can be a good choice for the patients for whom vasoconstrictor is contraindicated because not only does it have a milder vasodilatory effect than most other amides, but, when providing a block injection, it is the only intermediate duration (40-60 minutes) plain local anesthetic currently available.9

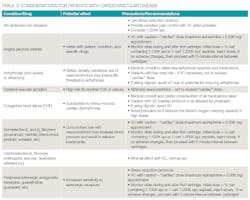

In most situations, limiting the amount of vasoconstrictor that a patient with cardiovascular disease receives produces an adequate benefit without compromising patient safety. For example, patients with a relative contraindication for vasoconstrictors may often receive the lowest possible dose of epinephrine, not to exceed the “cardiac” maximum recommended dose of 0.036 mg per appointment6 (see Tables 2, 3). The risks of using epinephrine versus the benefits should always be considered for each individual patient based upon their profile and history. Recall that inadequate pain control may result in the release of unpredictable amounts of endogenous epinephrine, perhaps exceeding the dose that would be provided by the hygienist.

Additional Strategies

Buffering of local anesthetic agents with sodium bicarbonate is another approach in aiding in stress reduction because patients don’t feel the “sting” of the agent, the anesthesia is more profound, and the onset is faster--perhaps reducing appointment time.7,10 In addition, it has been reported that its use may eliminate post injection pain the next day.4,9

Computer-controlled local anesthesia delivery systems (C-CLAD) have been shown to reduce pain perception, particularly for palatal injections, because of the fixed, slow, controlled delivery rates, 11,12) and, therefore may be useful for patients with cardiovascular disease.

Approved by the FDA in June 2016, the nasal local anesthetic spray, Kovanaze, containing 3% tetracaine HCl (ester) and 0.05% oxymetazoline HCl (vasoconstrictor), shows promise for reducing stress and anxiety because it is a “needleless” approach in providing maxillary local anesthesia. It has demonstrated adequate pulpal anesthesia for maxillary anterior and premolar teeth. Clinical trials, which included testing of the incisive papilla and the palatal foramen, reported some success with palatal anesthesia, particularly in the area of the incisive papilla.13,14

Because of the basic properties of articaine, which are very different than other amide injectable local anesthetics, it can be a very a desirable agent to use for patients with cardiovascular disease:4,15-17

• It has a high degree of lipid solubility due to the thiophene ring which promotes quick diffusion through hard and soft tissues resulting in profound anesthesia.

• Due to its ester linkage, articaine is rapidly metabolized in the blood with only 5-10% metabolized in in the liver. The resulting elimination half-life (the time required for 50% of drug to be removed from the blood) of articaine is significantly shorter than all other injectable amide agents (27-44 minutes versus 96-114 minutes). For a 98.5% reduction in blood levels, articaine takes less than 4.4 hours versus other amides which take 9.6 -11.4 hours. This may be significant for patients with cardiovascular disease with regard to decreasing toxicity.

Patients with cardiovascular disease may be medically unstable, present with multiple conditions/risk factors, and may be taking several medications. A thorough medical history, baseline vital signs with ongoing monitoring during care is good practice for promoting patient comfort and safety. Often a medical consultation to determine the patient’s medical status is required and a waiting period prior to elective procedures may be necessary. There should be careful consideration of the potential for drug interactions. It is particularly important to administer the lowest effective dose of local anesthetic using proper techniques and to employ anxiety and stress reduction protocols.

LAURA J. WEBB, RDH, MS, CDA, is an experienced clinician, educator, and speaker who founded LJW Education Services (ljweduserv.com). She provides educational methodology courses and accreditation consulting services for allied dental education programs and CE courses for clinicians. Laura frequently speaks on the topics of local anesthesia and nonsurgical periodontal instrumentation. She was the recipient of the 2012 ADHA Alfred C. Fones Award. Laura can be contacted at [email protected]

References

1. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2017 At-a-Glance. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/ahamah-public/@wcm/@sop/@smd/documents/downloadable/ucm_491265.pdf

2. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/heart-disease.htm

4. Logothetis, D. 2017. Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist 2nd ed. Elsevier

5. Wilkins E. 2013 Clinical Practice of Dental Hygiene, 11thed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

6. J Little, D Falace, C Miller, N Rhodus. 2017. Little and Falace’s Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient, 9th ed. Elsevier

7. M Darby, M Walsh. 2015 Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice 4th ed. Elsevier

8. Toile, SC & Waters, AN. Dental care for patients with heart disease. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015 Apr: 13(4):65-68

9. Malamed S. 2013 Handbook of Local Anesthesia 6th ed; Elsevier

10. Bizga, T. Cozy and numb. Dental Economics September 22, 2016

11. Chang, Hyeyung, et al. Relief of Injection Pain During Delivery of Local Anesthesia by Computer-Controlled Anesthetic Delivery System for Periodontal Surgery: Randomized Clinical Controlled Trial. J Periodontol. ٢٠١٦ Jul;٨٧(٧):٧٨٣-٩

12. DeMarco & Bassett. Pain Reduction Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2012 Mar; 10(3): 28, 31-32, 34-35.

13. Ciancio, Sebastian G. et al. Comparison of 3 intranasal mists for anesthetizing maxillary teeth in adults: A randomized, double-masked, multicenter phase 3 clinical trial. JADA 2015 May; 147(5); 339 - 347.e1

14. Hersh, Elliot V. et al. Double-masked randomized placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of intranasal K305 (3% tetracaine plus 0.05% oxymetazoline) in anesthetizing maxillary teeth. JADA 2016 Apr; 147(4); 278 – 287

15. Katyal V. The efficacy and safety of articaine versus lignocaine in dental treatments: a meta-analysis. J Dent. 2010 Apr; 38(4):307-17.

16. Costa CG, Toramano IP, Rocha RG, Francischone CE, Totamano N. Onset and duration periods of articaine and lidocaine on maxillary infiltration. j.prosdent. 2005 Oct; 94(4): 381

17. Batista da Silva C, Berto LA, Volpato MC, Ramacciato JC, Motta RH, Ranali J, Groppo FC. Anesthetic efficacy of articaine and lidocaine for incisive/mental nerve block. J Endod. ٢٠١٠ Mar; ٣٦(٣):٤٣٨-٤١.