Seeking Consensus About Dental Implants

By Lynne Slim, RDH, BSDH, MSDH

Edie Shuman-Gibson, RDH, and I have known each other since I trekked my way around the heart of the Rocky Mountains to a small Colorado college town called Crested Butte. At that time, she owned an unsupervised dental hygiene practice there, and I drove down from Denver to take photos and write about her bustling practice.

Fast forward about seven years and she is lecturing on evidence-based dental implant maintenance at the ADHA's annual session. I agreed with what she had to say about dental implant instrumentation. Susan Wingrove is another RDH whose textbook chapter on implant instrumentation caught my attention, and then there's Lisa Wadsworth, RDH, who frequently lectures/writes on this topic. Besides Edie, Susan, and Lisa, there's me, and I'm the nerdy/skeptical one who sometimes ends up disagreeing with the status quo.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Consider these articles by Lynne Slim

- Dental Implant Assessment

- Cement-associated peri-implantitis

- Is household bleach an effective biofilm killer

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Backing up a bit, let's review what limitations the average RDH faces today while instrumenting during a typical recare appointment. Besides not being able to order preferred instruments (which is a major frustration of a lot of practicing dental hygienists who complain about the lack of funding in their departments), the clock is king and I wrote about this dilemma last year in RDH magazine. When your employer raises both arms straight over his head like he's signaling for a touchdown and shouts, "The clock is king!" you struggle with efficiency in an attempt to survive a grueling daily schedule.

I keep this in mind whenever I hear people lecture on instrumentation, and that includes instrumenting around dental implants. Gone are the days when hygienists had 20 hand scalers (hand instruments/scalers including curettes) rolling around on the tray, unless they've just graduated and have a new set of Graceys for use right after a board exam! When it comes to instrumenting around a dental implant, safety, efficacy, and efficiency come to mind but I still don't see the need for a bunch of manual scalers specifically tailored for use around implant crowns, and we'll discuss this further.

Evidence-based dental hygiene, when applied appropriately, considers the use of best available evidence together with a clinician's expertise and patient preferences to provide clinical decision support at the point of care. So, let's look at the literature on dental implant instrumentation and discuss what a few top dental implant/hygiene clinicians and one periodontist in particular have to say that can be applied in our operatories when we're down in the mouth.

Just like the absence of consensus on health-care reform in the United States, there's a lack of agreement by oral health-care professionals on instrumentation around dental implants. Various methods have been recommended, but there is no established gold standard (for example plastic hand scalers, graphite and titanium hand scalers, ultrasonic scalers covered with plastic or carbon composite tips, air abrasives, polishing rubber cups).1

In preparing for this column, I read several relevant articles, a new book chapter on implant maintenance/instrumentation and a systematic review (SR) on titanium surface alterations following the use of different mechanical instruments. In reading an SR, it's not only important to read the abstract or discussion/conclusion section but it's also important to focus on clinical significance. Out of 3,275 papers identified on the topic in the systematic review, only 34 met the authors' criteria, and different mechanical instruments were used. Most of the studies were in vitro studies, and there was a wide variation in treatment parameters: number of strokes, treatment time, force applied, angulation of the instrument, distance from the treated surface, and number of treated surfaces.

In addition, the estimated risk of bias from 25 out of 34 studies was considered to be high. The SR focused on damage to smooth and rough titanium surfaces. SR authors concluded nonmetal instruments appear to be "implant safe" because they cause almost no damage to implant surfaces, and a variety of these instrument types were used. For polishing, rubber cups -- both with and without various pastes -- and air polishing with different abrasives was also considered relatively safe.1 Treatment of a smooth implant surface with an ultrasonic device with a nonmetal tip caused no visible changes to the surface in most studies.1 Titanium curettes resulted in less pronounced surface damage than did metal curettes and ultrasonics with metal tips.1

However, the authors questioned the clinical significance of the collective studies because there was no standardization in technique or instruments that measured surface roughness, which makes it difficult to compare values from one study to another. Sample sizes were small, too, and only papers in English were included in the SR.

Susan Wingrove, RDH, weighs in with her implant instrument suggestions based on her expertise and extensive study of the dental implant literature, and she does not recommend plastic scalers or air-powder polishing systems because she found that they leave deposits (residue) on the titanium implant surfaces.2

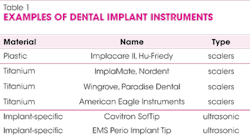

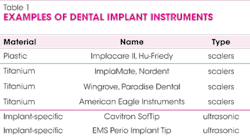

Instead, Susan recommends medical grade titanium scalers because they are biocompatible and thinner than plastic implant scalers. They also provide the needed strength to dislodge calculus and even residue cement. Susan recommends magnetostrictive and piezo implant-specific ultrasonic inserts/tips (see Table I for examples of manual and ultrasonic implant scalers). Susan Wingrove's book chapter on implant maintenance is a valuable resource, and she provides many details about protocols for maintaining various types of implant prostheses.

Lisa Wadsworth, RDH, cites studies showing damage to implant surfaces when traditional metal ultrasonic tips/inserts are used, and she recommends ultrasonic implant-specific inserts/tips.

If hand scaling around an implant crown, she prefers scalers made of plastic or acrylic resin.3 For polishing, Lisa educates hygienists to use nonabrasive polishing pastes like tin oxide around the titanium portion of an implant prosthesis.

Dr. Timothy Hempton, a periodontist and associate clinical professor at Tufts University School of Dental Medicine chatted briefly about implant maintenance and he referred me to one of his recent publications.4 Dr. Hempton classifies implant maintenance according to degree of exposure of abutment or actual implant. He discusses several in vitro studies that compare metal to nonmetal mechanical instruments, as well as the degree of damage to implant abutments when using a metal instrument. Scratching of implant abutments is assumed to make the smooth surface of the abutment or implant more plaque retentive, and there is research that demonstrates this association. He also cites a study, however, that demonstrated a reduction in bacterial adhesion when the rough titanium surfaces were instrumented with metal curettes compared to smooth titanium surfaces.

Dr. Hempton also threw a wrench into the thought process for me, however, when he explained that most implant systems now have a roughened surface and many have eliminated the polished (smooth) collars associated with the most coronal aspect of the implant. He suggests that if the actual implant is exposed, metal scalers may reduce implant surface roughness, making them less plaque retentive.4

For a Class I implant maintenance case (healthy clinical scenario with no exposure of the abutment), Dr. Hempton recommends using the same mechanical instruments you would use for a natural dentition. The reason is that the only portion of the implant-supported crown you can access is the prosthesis or crown itself. Moreover, he is concerned that the use of a plastic scaler would fail to remove calculus effectively from the crown.

Regarding Class II implant maintenance cases (probing depths greater than 4 mm or some moderate peri-implant soft tissue recession exposing the abutment), conventional mechanical instruments (hand and ultrasonic) could be utilized to debride the prosthesis. Plastic and/or implant-specific ultrasonic inserts/tips could then be used on any exposed portions of the abutment to prevent scratching.

Class III implant maintenance scenarios (peri-implantitis with exposure of the implant itself) should be referred to a periodontist for evaluation. If debriding before referral, consider utilizing conventional mechanical instruments (hand and ultrasonic). In addition, consider utilizing titanium metal instruments to remove plaque and calculus. As previously mentioned, metal instrumentation will likely reduce bacterial adhesion on rough implant surfaces.4

Roughened implant surfaces or exposed threads should not be scaled with plastic instruments, according to Dr. Hempton, and that includes plastic implant-specific ultrasonic tips. Small plastic fragments may engage the roughened implant surface and or remain in the subgingival area.4

Dr. Hempton mentions air-powder polishing systems and cites the in vitro studies that show efficacy and safety, but he also cautions that improper use of an air abrasive device (including the use of an inappropriate powder) can cause trauma to the tissue surrounding an implant, alter the abutment or implant surface, and result in tissue emphysema.4

Edie Gibson agrees with Dr. Hempton about not using a plastic implant scaler on a roughened surface, but recommends it for biofilm/plaque removal. She believes in customizing an implant instrumentation protocol and likes both Susan Wingrove's and Dr. Hempton's instrumentation suggestions. She recommends the solid medical grade titanium instruments that are claimed to be soft enough not to scratch the implant yet rigid enough to remove calculus.

I always advise dental hygienists to do their homework carefully before adopting a certain protocol. That means reading SRs and making up one's mind after listening to experts and reading everything one can on the subject. The average dental hygiene clinician like me is mostly instrumenting around single implant crowns at recare appointments that require little instrumentation other than biofilm disruption. Don't be heavy handed with the instruments you select and proceed with caution. There is a tremendous need for evidence-based clinical guidelines on this important subject.

LYNNE SLIM, RDH, BSDH, MSDH, is an awardwinning writer who has published extensively in dental/dental hygiene journals. Lynne is the CEO of Perio C Dent, a dental practice management company that specializes in the incorporation of conservative periodontal therapy into the hygiene department of dental practices. Lynne is also the owner and moderator of the periotherapist yahoo group: www.yahoogroups.com/group/periotherapist. Lynne speaks on the topic of conservative periodontal therapy and other dental hygiene-related topics. She can be reached at [email protected] or www.periocdent.com.

References

1. Louropoulou A, Slot DE, Van der Weijden F. Titanium surface alterations following the use of different mechanical instruments: a systematic review. Clin. Oral Impl. Res. 23, 2012 643–658

2. Wingrove S. (2013) Peri-implant therapy for the dental hygienist: clinical guide to maintenance and disease complications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

3. http://www.dentistrytoday.com/articles-hygiene/8674-common-threads-care-and-maintenance-of-implants

4. http://www.dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/ddhright.aspx?id=10235