Dental hygienists across the country are either adjunctively incorporating lasers into their patient care, or they’re thinking about incorporating lasers. Patients often call dental offices asking for laser treatment, even if they aren’t sure of the benefits.

Lasers in dentistry are used to cut hard and soft tissue, whiten, desensitize teeth, manage oral lesions, and much more. It’s clear we aren’t going back to an era before lasers, but how does adjunctive laser use by dental hygienists alter outcomes? In order to explore this question, it’s helpful to remember that oral inflammatory conditions are diseases that rely on a pathogenic shift in the biofilm to initiate disease, yet they manifest themselves differently depending on the host response. Therefore, attempts to reduce inflammation, reduce pathogen load, or improve healing will be highly contingent upon the host and its response to interventions, including laser treatment. To date, we do not possess a “silver bullet” to eradicate oral diseases, but the incorporation of laser energy to inflamed oral tissues has the potential to improve outcomes related to tissue integrity, pain management, and wound healing.

Where’s the evidence?

Most dental hygienists who routinely use lasers during periodontal maintenance or active therapy anecdotally confirm superior clinical outcomes—less bleeding, faster healing, improved clinical attachment levels, and improved tissue integrity—with adjunctive use of lasers compared to not incorporating lasers. But what does the science say?

The answer is not straightforward. In addition to studying design variables (i.e., randomized controls, clinical case studies, cohort studies, and case reports), consider the variables that may or may not be calculated into clinical study outcomes: depth of penetration of the laser wavelength into the tissues, degree of inflammation present and whether or not the tissue is keratinized, variation in diameter of the optic fibers, power settings, whether or not the laser is pulsed or continuous energy, and expertise of the clinician using the laser when evaluated in vivo.

Not surprisingly, evidence to date is mixed and remains controversial. A recent review of the literature confirms both superior periodontal outcomes with adjunctive use of lasers and no clinical or measurable differences.1 When the evidence is conflicting, ask, “Do we not have evidence, and will we ever have it because the theory is flawed?” or “Do we not have evidence because not enough well-designed studies have been conducted to confirm the results we are seeking?”

Despite the fact that we know the need exists for more well-designed studies with controlled variables that can easily skew results, many clinicians have lasers and use them daily. So, let’s consider the potential benefits to adjunctive lasers, assuming clinicians have been trained in laser use and safety.

Lasers for periodontal health

Depending on the type of laser and wattage used, dental hygienists can use lasers for a variety of procedures, including treatment of painful aphthous ulcers (figure 1) and desensitizing teeth. But the most likely use of lasers by dental hygienists is in their efforts to achieve and sustain periodontal health. As biofilms shift, becoming favorable to promoting the survival and growth of pro-inflammatory pathogens, specific pathogens emerge that promote disease inside and outside of the oral cavity in susceptible hosts.

The immune response to these pathogens produces an increase in proinflammatory cytokines. The cascade of events at a cellular level then relies on host responses unable to dampen the effects of these proinflammatory cytokines, and chronic inflammatory conditions ensue. What can lasers bring to this disease cascade that might help generate different outcomes? Lasers can potentially influence health in the oral cavity through the following mechanisms—antimicrobial effects, debridement of the contaminated root surfaces, and biostimulation.

Most of the gram-negative anaerobic bacteria thriving below the gumline are sensitive to the thermal heat provided by the laser energy, and some laser wavelengths are attracted to darker pigmented bacteria. The laser tip navigating into a furcation or deep pockets where tissue is inflamed can act as a magnet targeting black pigmented pathogens to reduce overall microbial population in diseased pockets (figure 2). Even though much of the published literature to date on antimicrobial effects of lasers in periodontal pockets is mixed, a recent study highlights the potential of lasers on three key pathogens tested: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia.

Twenty participants with pocket depths greater than or equal to 6 mm and positive for these three pathogens were divided into two groups, with the test group undergoing scaling and root planing (SRP) and laser decontamination, and the control group undergoing only SRP. Assessments two months post-treatment confirmed significantly improved clinical parameters of clinical attachment levels (CAL), oral hygiene (OH), probing pocket depths (PPD), and gingival index (GI) with the test group compared to the control.

Microbiological data before and after also confirmed a significantly greater reduction in the three key pathogens in the SRP and laser group compared to SRP alone.2 Additionally, a recent study published in the International Journal of Dental Hygiene reported similar improved clinical outcomes and antimicrobial results against key periodontal pathogens when comparing SRP and laser to SRP alone, even though the power used in that study was low-level laser therapy (LLLT).3 More well-designed studies with controlled variables are necessary to fully appreciate the antimicrobial potential of lasers related to periodontal health, but clearly this subject continues to be of interest to many researchers as evidenced by an online search of the topic.

Debridement of the root surface to remove necrotic tissue can be beneficial but can also have negative results depending on the wavelength, technique, and type of laser used. Er:YAG lasers can be used to remove calculus from root surfaces, but diode and Nd:YAG lasers penetrate deeper and should be used with caution for debridement, with the exception of diode lasers used at a low wavelength with photodynamic therapy for potential antimicrobial benefits.

Biostimulation using low-level lasers appears to be promising in reducing inflammation, and thereby improving wound healing. This is an area where clinicians routinely anecdotally confirm low-level laser use inside diseased periodontal pockets reduces pain and bleeding upon probing, expedites wound healing, and enhances CAL post-SRP compared to non-laser use. Evidence from published literature at this point appears to be mixed, but recent studies have examined the benefits of LLLT for flap surgical sites compared to those without biostimulation. They report less pain with adjunctive laser treatment,4 and reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines during periodontal therapy with adjunctive LLLT compared to those without.5

Hopefully, in the near future, enough well-designed studies will answer some of the questions related to optimal power, duration, and penetration for biostimulation to provide the best outcomes for a variety of oral conditions. LLLT has been used broadly outside of the oral cavity with commercial devices to help reduce pain by reducing inflammation for those with back pain, arthritis, irritable bowel diseases, and many other inflammatory conditions (figure 3).

Lasers ideally suited for dental hygienists

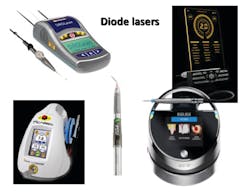

When deciding on the type of laser for use by dental hygienists, cost, ease of use, the footprint of the device, effectiveness for desired procedures, cordless foot switches, and portability all come into play. This makes a diode laser the ideal choice for most dental hygienists (figure 4). Even though most states allow dental hygienists to use lasers, clinicians should stay abreast of state regulations, statutes, and certifications surrounding laser usage. The Academy of Laser Dentistry provides training and certification for dental hygienists.

When purchasing a diode laser, consider laser tip size (ideally 0.4 mm) in order to navigate sulcus and pocket topography subgingivally (figure 5). Disposable tips, while slightly more expensive, have an advantage over the inconvenience of cleaving a new tip with each use. Graphic presets to quickly and easily select the desired wattage, and the option to have continuous or pulsed settings, are other desirable features. Diode lasers should be kept in the dental hygiene operatory for ease of use, as indicated, with appropriate safety precautions taken for the patient and hygienist.

What is the return on investment?

Diode lasers for dental hygienists are not cost prohibitive investments for dental practices when considering the enhancement to periodontal treatments and use in other dental procedures, including laser whitening and soft-tissue procedures. While there are no reimbursement third-party codes specific to use of the lasers for various treatments, many practices increase the fee for nonsurgical periodontal procedures by as much as 50% while other practices incorporate laser treatment into dental hygiene procedures as value-added services.

Developing a script to enroll patients into a laser-assisted treatment plan not only educates patients but increases the value of services your practice provides. Laser technology to periodontal debridement can enhance results by antimicrobial effects, overall tissue response, including postoperative patient comfort and expedited healing through biostimulation. Patients often seek dental care that incorporates lasers. Educating potential patients on your website about your use of lasers might increase new-patient attraction. What are you waiting for?

References

1. Bowen D. The use of lasers in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Dimens Dent Hyg. 2017 Feb;15(2):54-57.

2. Fenol A, Chinnu-Boban N, Jayachandran P, Shereef M, Balakrishnan B, Lakshmi P. A qualitative analysis of periodontal pathogens in chronic periodontitis patients after nonsurgical periodontal therapy with and without diode laser disinfection using benzoyl-DL arginine2-Napthylamide test: A randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018 Jul-Sep;9(3):382-387.

3. Petrovic MS, Kannosh IY, Milasin JM, Mihailovic DS, Obradovic RR, Bubanj SR, Kesic LG. Clinical, microbiological and cytomorphometric evaluation of low-level laser therapy as an adjunct to periodontal therapy in patients with chronic periodontitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2018 May;16(2);e120-e127.

4. Heidari M, Fekrazad R, Sobouti F, Moharrami M, Azizi S, Nokhbatolfoghahaei H, Khatami M. Evaluating the effect of photobiomodulation with a 940-nm diode laser on post-operative pain in periodontal flap surgery. Lasers Med Sci. 2018 Nov;33(8):1639-1645.

5. Mastrangelo F, Dedola A, Cattoni F, Ferrini F, Bova F, Tatullo M, Gherlone E, Lo Muzio L. Etiological periodontal treatment with and without low-level laser therapy on IL-1β level in gingival crevicular fluid: an in vivo multicentric pilot study. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2018 Mar-Apr;32(2):425-431.

Karen Davis, BSDH, RDH, is the founder of Cutting Edge Concepts, an international continuing education company. She practices dental hygiene in Dallas, Texas. She is an independent consultant to the Philips Corporation, Periosciences, and Hu-Friedy/EMS. She can be reached at [email protected].

Samuel B. Low, DDS, MEd, MS, has 30 years of private practice experience in periodontics and implant placement. He was an associate faculty member of the L.D. Pankey Institute for 20 years and professor emeritus at the University of Florida College of Dentistry. His awards and achievements include past president the American Academy of Periodontology, Dentist of the Year from the Florida Dental Association, Gordon Christensen Lecturer Recognition Award, and former trustee of the American Dental Association.