Understanding the function and location of muscles in the head and neck area allows hygienists to recognize abnormalities in a patient’s anatomy.

Knowledge of the muscles in the head and neck region is imperative for dental hygienists. Patient exams, including oral cancer exams, integrate assessment of this region’s musculature. Understanding the function and location of the muscles allows us to recognize any abnormalities in a patient’s anatomy. An abnormality can affect a person’s eating, speaking, and expression, as well as a dental hygienist’s patient-management protocols and treatment plan. This article will serve as a review of the muscles of the head and neck directly associated with dental hygiene care. In addition, the implications for dental hygiene care will be addressed.

Head and neck muscles

A muscle is defined as a body tissue consisting of long cells that contract when stimulated, producing movement. Each muscle has an origin and insertion. The origin is the more fixed, central, or larger attachment of the muscle.1 The part of the muscle that inserts and is attached to the more movable structure is the insertion.1,2

The muscles of the head and neck region are divided into several groups: cervical muscles, muscles of facial expression, muscles of mastication, hyoid muscles, and muscles of the tongue, pharynx, and soft palate.

•Cervical muscles - A function of the muscles of the neck, or cervical, region is to hold and stabilize the head.3 In addition, these muscles position the head in relation to the rest of the body.2,3,4 The two largest and most superficially located cervical muscles are the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the trapezius muscle.

•Muscles of facial expression - The muscles of facial expression work in groups to change the appearance of the face. All of these muscles are found bilaterally, or paired.2,3,4 These muscles originate on bone, and insert on skin tissues of the face, scalp, and neck.2,3,4 The seventh cranial nerve, the facial nerve, innervates all of the muscles of facial expression.2,3,4

The orbicularis oris muscle encircles the mouth and allows the lips to be pursed. The buccinator muscle assists in mastication as well as compressing the cheeks and pulling the angle of the mouth up. Both the risorius and levator labii superioris muscles widen the lips as in a smile. Zygomaticus major and minor muscles along with the levator anguli oris elevate the upper lip and lift and pull the angles of the mouth laterally. As the names indicate, the depressor anguli oris and the depressor labii inferioris muscles depress the lower lip and angles of the mouth. The mentalis muscle protrudes the lower lip as in a pout. Running from the neck to the mouth, the platysma muscle raises the skin of the neck and pulls down the angles of the mouth as in a grimace.

•Muscles of mastication - Responsible for the depression, elevation, protrusion, retraction, and lateral deviation of the mandible are the muscles of mastication.2,3,4 Located deep in the face, these paired muscles are innervated by the fifth cranial nerve.2,3,4 The masseter muscle has superficial and deep muscle heads. The temporalis muscle is a broad, fan-shaped muscle that elevates and retracts the mandible. Another elevator of the mandible is the medial pterygoid. The lateral pterygoid has superior and inferior heads. These heads help to stabilize, depress, and protrude the mandible.

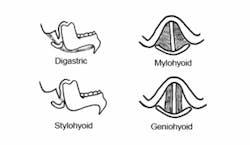

•Hyoid muscles - The hyoid muscles are all attached to the hyoid bone.2 These muscles assist in mastication and swallowing. The hyoid muscles are grouped according to their relation to the hyoid bone into suprahyoid and infrahyoid groups.2,3 The suprahyoid muscle group is also divided into anterior and posterior groupings according to their position.2,3

The suprahyoid muscles are located superior to the hyoid bone and have the action of elevating the hyoid and larynx.2,3 These muscles are the digastric, mylohyoid, stylohyoid, and geniohyoid. The digastric has anterior and posterior bellies that are separated by an intermediate tendon. The mylohyoid also helps in elevating the tongue.

The infrahyoid muscle group is located inferior to the hyoid bone. The action of these muscles is to depress the thyroid cartilage or the hyoid bone.2,3 The infrahyoid muscles are the sternothyroid, sternohyoid, omohyoid, and thyrohyoid muscles. The thyrohyoid muscle depresses the hyoid bone and raises the thyroid cartilage and larynx.

•Muscles of the tongue - Muscles of the tongue are divided into intrinsic and extrinsic muscles according to their origin.2,3,4 The tongue is divided symmetrically on the median plane with intrinsic and extrinsic muscles on both sides.

The intrinsic tongue muscles are confined within the tongue itself.2,3,4 These help to alter the shape of the tongue. There are three types of intrinsic muscles named according to their orientation in the tongue: longitudinal, transverse, and vertical.2,3,4

The extrinsic muscles of the tongue originate outside of the tongue.2,3,4 Originating on the genial tubercles, the genioglossus protrudes and depresses the tip of the tongue. The hyoglossus originates on the hyoid bone to depress the tongue. The styloglossus retracts the tongue and elevates the tip. The palatoglossus comes from the soft palate to elevate the posterior portion of the tongue and pull it backward.

•Muscles of the pharynx - The muscles of the pharynx help a patient to swallow, speak, and hear.2 These muscles are the stylopharyngeus and pharyngeal constrictors. The pharyngeal constrictors are divided into superior, middle, and inferior groups.

• Muscles of the soft palate - The muscles of the soft palate are used in speaking and swallowing.2 The muscles of the soft palate are the palatoglossus, palatophyngeus, levator veli palatine, tensor veli palatine, and the uvula. The palatoglossus forms the anterior tonsillar pillars, while the palatophyngeus forms the posterior tonsillar pillars.

Influence on dental hygiene care

A patient who has damage to the muscles of the head and neck region may have various issues, which may in turn affect the management of dental hygiene treatment.

The cervical muscles change the way in which a patient’s head and neck are positioned. The patient may not have the ability to place his/her body in a traditional or ergonomically correct position for the dental hygienist. A muscle dysfunction of this region can cause the head to move to one side or the other, and the patient may not be able to raise his/her chin. A hygienist should use additional supports and stabilizers, such as pillows, to make the patient comfortable and in an ergonomically correct position for the clinician.

The muscles of facial expression give an individual the ability to laugh, cry, smile, and frown.7 Damage to these muscles, which would impact these basic functions, could bring about inconvenience and distress to a patient. As the patient’s oral health-care provider, the hygienist must be aware of this and handle the situation with sensitivity. An injury to the muscles of facial expression may lead to abnormal movements of this region. Twitching, spasm, weakness, or paralysis would not be uncommon.7 The patient may experience altered taste sensation and dryness of the mouth. On the contrary, if a patient does not have the ability to close his/her lips, he/she may experience excessive drooling.8 A familiar cause of facial weakness is called Bell’s palsy. A patient with Bell’s palsy may have similar symptoms as those noted above. Currently, there is no curative treatment for Bell’s palsy.9

Impairment to the four muscles of mastication can greatly influence dental hygiene care. A patient may have difficulty during dental hygiene treatment when opening, swallowing, achieving adequate plaque removal, taking impressions, and tolerating the length of an appointment. A mouth prop can be used to help open a patient’s mouth. In very difficult cases of clenching or a malposition of the temporomandibular joint, a muscle relaxant may be prescribed to make opening more feasible. Coughing, gagging, choking, and aspiration may also become factors for which the dental hygienist must account.8 Having your patient in a slightly upright position and slightly turned to one side may help lessen these problems.8 Without appropriate swallowing, food may stay in the oral cavity for longer periods of time, which will lead to an increased caries rate if the patient is not made aware of the situation or does not have the ability to manage it. A fluoride supplement or an antimicrobial rinse could be an option to assist the patient.

The hyoid muscles and the muscles of the tongue will impact the patient’s ability to properly masticate, swallow, speak, and position his/her tongue. The tongue may become atrophied in severe cases. A dental hygienist must allow the patient to communicate to the best of his/her ability. This may take additional time. The hygienist must also consider the tongue’s position when doing procedures such as taking impressions. Instruction and practice may help the patient, or the practitioner may have to move the tongue for the patient. Damage to these muscles can also influence salivary flow. If the flow is excessive and leaves the mouth, the patient may have extraoral skin sores.

Conclusion

The muscles in the head and neck region are directly related to dental hygiene care. A thorough knowledge of the musculature in this region will enhance the examinations given to dental hygiene patients, help to identify any possible anomalies, and make the hygienist aware of any additional services these patients may need. A dental hygienist should allow additional time to be with these patients when possible. Having additional stabilizers and supports, such as pillows and mouth props, might help the patient’s comfort. Introducing alternative oral hygiene techniques and adjuncts, such as toothbrush options and use of antimicrobial and fluoride supplements, may improve the patient’s home-care results. Watching the patient’s functional habits to stop any excessive or further damage from occurring will support the patient’s needs. Stressing the importance of regular maintenance visits will help both the patient’s and the hygienist’s goal of a healthy mouth to be met. Lastly, refer your patient for further evaluation with a

speech language pathologist, occupational therapist, other dental professional, or other health-care provider for comprehensive, interdisciplinary care for the patient.

References

1 Merriam Webster On-Line Dictionary. http://www.m-w.com/. Available July 11, 2005.

2 Fehrenbach M, Herring S. Illustrated anatomy of the head and neck. W.B. Saunders Company 1996.

3 Smith S, Karst N. Head and neck histology and anatomy: a self instructional program. Appleton and Lange 2000.

4 Hiatt J, Gartner L. Textbook of head and neck anatomy. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. 3rd Edition.

5 Liebgott B. The anatomical basis of dentistry. Mosby. 2nd Edition.

6 Martini F. Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology. Prentice Hall College Division. 5th Edition.

7 Facial nerve disorders. http://www.entcolumbia.org/fndis.htm. Available Nov. 28, 2005.

8 Bell’s palsy. http://www.entcolumbia.org/bells.htm. Available Nov. 28, 2005.

9 National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. National Oral Health Information Clearinghouse. Practical Oral Care for People with Developmental Disabilities. NIH Publication No. 04-5192. Printed May 2004.