Getting past “not my child”: The dental hygienist’s role in detecting developmental delays and pediatric sleep apnea

Over the past several years, there has been an increase in the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of sleep apnea in both adults and children. Sleep apnea has been associated with a myriad of symptoms, including snoring, sleep deprivation, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and learning and memory difficulties. Without treatment, sleep apnea has been implicated in hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias or other cardiac issues, and stroke.1

Yet the youngest of our patients, those from birth to age 5 or 6, may be labeled “irritable” or “difficult” when in fact, sleep apnea or other issues may be the cause. Much like sleep apnea, developmental delays are often overlooked in diagnosis and treatment. When the subject of a possible developmental delay is broached, many parents become defensive as the “not my child” thought process intervenes. As dental professionals, understanding the basics of a developmental delay and referring patients to appropriate providers and resources can improve the outcome for the child and family.

Developmental delays

A developmental delay occurs when a child does not reach his or her developmental milestones at the expected times.2 Delays may be in one or more areas of development such as speech/language skills or fine/gross motor skills. Skills may be present but developing at a slower rate than normal. Each child is a unique individual; therefore, milestones are ranges for various activities.

A developmental disorder, however, indicates that developmental skills or milestones are developing abnormally. A developmentaldisorder is defined as a severe, chronic disability of an individual who has a mental or physical impairment by age 22 that is likely to continue indefinitely and results in substantial functional limitations in three or more areas of major life activities.3 Common developmental disorders include the autism spectrum, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, spina bifida, hearing or vision impairments, and intellectual disabilities. Causes of delays or disorders range from genetic defects to complications of pregnancy and birth, and for younger children, frequent ear infections, colds, or allergies.2

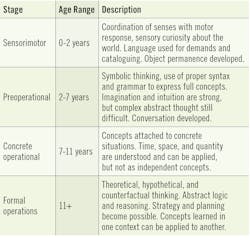

In the 1930s, Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget developed the theory of cognitive development. Understanding children from birth and beyond, Piaget believed that children are born with a very basic mental structure (genetically inherited and evolved) on which all subsequent learning and knowledge are based (see table 1).4 Based on this theory, the medical profession developed age-appropriate milestones that define a delay or disorder. These milestones assess ability in the following areas: social/emotional, language/communication, cognitive, and movement/physical.

Influence of prematurity

A child born prematurely may be lagging in some areas with an adjusted gross age. Adjusted gross age is represented by the age of the child when they are born minus the age they would have been if born on the expected delivery date. For example, a child born 6 weeks premature, at 8 weeks of age would be expected to be doing what a 2-week-old child of normal delivery would be expected to do. This age adjustment usually flattens out by age 3 so that the premature child will begin to reach normal age developmental milestones. All children continue on an individual developmental path that is unique but follows certain guidelines. For example, a baby at 6 months old should like to look in the mirror (social/emotional), respond to own name (language/communication), bring things to mouth (cognitive), and sit without support (movement/physical).6 A premature infant born two months early at 4 months old would do what a 2-month-old would be expected to do: begin to smile (social), turn head to sound (language), begin to follow things with eyes (cognitive), and begin to hold head up (movement).

Our responsibility

There are a variety of nuances to each developmental stage, and trained medical professionals in each area (psychological, speech/language, physical and occupational therapists) are the best resources to diagnose and treat delays. As dental professionals, it is our responsibility to refer our patients, even the youngest and their families/caregivers, to the appropriate resources. When an adult patient in the dental chair exhibits hypertension, we refer to the primary care provider for more information; it should be no different when it comes to our youngest patients. Health-care experts recommend that children be seen by a dental professional by age 1 or within 6 months after the first tooth erupts.7–9 This first visit allows the dental professional to educate the parent/caregiver about home care, effects of nutrition, decay, and other preventive measures. It also provides the family with a “dental home.”

Speech, language, and healthy oral function

As part of the screening process, questions can be asked of the parent/caregiver on the child’s medical history if there are any concerns about the child’s development, particularly in the area of speech and language since the mouth is essential to speech development and communication. Communication involves speech, language, and listening. Without the ability to form words correctly, a child may have difficulty with speech and thus communication. An infant or a young child exhibiting a tight frenum, tongue thrusting, oral sensitivities, enlarged tonsils/adenoids, thumb-/digit-sucking, pacifier use, or mouth-breathing may experience speech/language difficulties or delays. Pediatric sleep apnea has been tied to learning and behavioral problems, poor weight gain, and hyperactivity.

Reviewing any concerns with the parent/caregiver can open the door to conversations about speech and language and prompt appropriate referrals. Whether referrals involve an early intervention program (birth to age 3 or 5, depending on state regulations), the special education department of the local school system, or dental specialist referral, the earlier the child receives a diagnosis and treatment for a developmental delay, the better the outcome for both the child and family.

Having difficult conversations

Approaching a parent/caregiver with concerns regarding a possible delay can often be a difficult conversation. Forging a relationship with a local early intervention program and/or pediatric medical practice is a good first step toward providing the dental team with resources for seeking advice on how to handle these conversations. Using the medical history as a starting point and applying patient engagement educational tools can assist, along with any conversation starters the medical professionals recommend.

Conclusion

As dental professionals we treat and educate a variety of patients, from the very young to the very old and everyone in between. For our youngest patients who may not be able to communicate, our educational responsibility lies with the parent/caregiver. Educating parents/caregivers on potential concerns we notice as part of the dental exam process can result in a lifelong benefit to the child, going far beyond his or her dental health alone. Considering the fact that many parents/caregivers have put off well-child visits during the pandemic, dental professionals have an even greater responsibility to educate about any potential developmental concerns.

REFERENCES

- Sleep apnea. SleepFoundation.org. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-apnea

- Developmental milestones. C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital. http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/devdel.htm

- Developmental disorders. Kennedy Krieger Institute. https://www.kennedykrieger.org/patient-care/conditions/developmental-disorders

- Piaget’s 4 stages of cognitive development. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html

- Piaget’s theory. The Psychology Notes Headquarter. http://www.psychologynoteshq.com

- Developmental checklists. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/checklists/all_checklists.pdf

- Section on oral health. Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1224-1229. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2984

- Your baby’s first dental visit. Mouth Healthy, brought to you by the American Dental Association.https://www.mouthhealthy.org/en/babies-and-kids/first-dental-visit

- Milestones for mini mouths. American Academy of Pediatrics. January 2019. https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/Infant_Oral_Health_Infographic_English.pdf