by Nancy W. Burkhart, RDH, EdD

[email protected]

Your patient today is a 54-year-old woman, Adele. As you seat her, you notice that Adele is wearing gloves. Since it is summer, your attention is focused on her covered hands and long sleeve sweater. As you take the health history and begin a conversation with her, you learn that Adele has been diagnosed with scleroderma or progressive systemic sclerosis. Since you have not seen a patient with scleroderma clinically, you quickly try to remember what you learned about this disorder in college. Would wearing gloves during the summer have anything to do with scleroderma?

Etiology: Although the etiology of scleroderma is not fully understood, it is classified as an autoimmune disease. According to the Scleroderma Foundation, approximately 300,000 cases exist in the United States; one-third of these cases are classified as systemic scleroderma, occurring most often in adults. The localized forms occur most often in children.

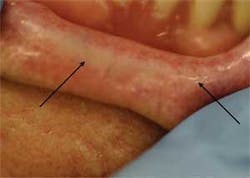

Fibrotic tissue exhibited by the tan band around the midline-inner part of the lip.

The term progressive systemic sclerosis is synonymous with systemic scleroderma. The PSS classification is made on the basis of the involvement of both skin and organs. As with most autoimmune disorders, women are most frequently diagnosed. Three to four times as many females as males develop the disorder, and the incidence is higher in African-Americans. The average age ranges from 25-55 years old. Other autoimmune disorders such as lupus and Sjogren's syndrome may exist in conjunction with scleroderma.

Constriction of oral tissues; patient with microstomia. Courtesy of Dr. T.D. Rees

Pathogenesis: Scleroderma is chronic in nature with sclerosis (thickening and hardening) of the connective tissues presenting in both local and systemic forms. Reports in recent years have linked some autoimmune disease states to occupational and environmental exposures.2,4

Radiograph of widened periodontal ligament space. Courtesy of Dr. T.D. Rees

Perioral and intraoral characteristics: Depending upon the extent of the disorder, the patient may exhibit constriction of the mouth (microstomia) and an inability to close the lips, due to the amount of fibrosis (see Figures 1 and 2). In Figure 1, a band of thick fibrotic tissue is evident on the lip extending to the wet line of the lip. In Figure 2, the skin and oral tissues are tight even with the aid of mirrors. Leader5 suggests a physical therapy technique used to increase the mouth opening over time: Lubricate the mouth, have the patient cross arms at chest height, with palms facing down, and use the thumbs to stretch the corners of the mouth for several minutes. Over time, the tissue may become more flexible. TMJ problems may be pronounced due to tissue constriction.

Isolated skin lesion occurring on lip, extending into gingival tissues. Courtesy of Dr. T.D. Rees

Scleroderma may occasionally be associated with idiopathic resorption of teeth and bone. Periodontal ligament widening may be a part of the characteristics and noticeable on radiographs (see Figure 3). A loss of the attached gingiva and noted recession may be seen in some patients with CREST (see related article on “Forms of Scleroderma”).

Patient exhibits tight skin with fingertip missing due to necrosis of skin. Courtesy of Dr. T.D. Rees

The patient presented in Figure 1 has had some grafting performed because of recession. Rigidity of the tongue and xerostomia are continuing major problems for the patient. Sjogren's syndrome is common, producing dryness in all salivary tissue and lacrimal glands.

This patient exhibits Raynaud's phenomenon.

Significant microscopic characteristics: Clinical and laboratory diagnosis is usually made for patients with scleroderma. Microscopically, tissue fibrosis with excessive collagen production is noted and the tissues typically show a marked reduction in open blood vessels.

This patient is beginning to exhibit sclerodactyly; patient exhibits an area of telangiectasia on finger.

Dental implications: Constriction of the oral tissues is an issue with disease progression, and this loss of dexterity pose problems for the patient. Instruction in home care procedures that meet the patient's needs should be addressed with modifications when needed. Electric toothbrushes and large flat handled brushes such as the Radius that are made for both right- and left-handed individuals are appropriate.

A patient who exhibits Sjogren's syndrome is at increased risk for both caries and periodontal problems. Patients with xerostomia need oral lubricants and fluoride treatments more frequently.

Candida is usually a problem because of the xerostomia and certain medications used by the patient may contribute to even more dryness.

The dental treatment should meet the needs of the specific patient. Smoking cessation is crucial in the management of scleroderma and Raynaud's phenomenon. Since smoking cessation is often delegated to dental facilities, this may fall into the realm of the dental practice.

Treatment and prognosis: Treatment and prognosis depends upon the type of scleroderma and specific involvement of various organs and tissues as the disease progresses. Frequent professional cleanings, examinations, and periodontal evaluations are necessary for long-term care. Caries and periodontal involvement may be lessened with careful monitoring and patient care early in the disease process. Medications used for blood vessel relaxation such as calcium channel blockers are often prescribed for scleroderma and Raynaud's. The medications may result in drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Depression may be a factor for some patients as with anyone who has a severe, chronic disease.

The dental professional may be the first person to witness the changes in this disease and may, in fact, be the person who gets the patient to the appropriate medical facility during the early stages. Early treatment and recognition is crucial in preventing caries, periodontal disease, and lessening destruction of the oral tissues.

For more information, contact:

- Scleroderma Foundation, [email protected] or visit http://www.scleroderma.org

- Juvenile Scleroderma Network, Inc., [email protected] or http://www.jsdn.org

References

- Albilia JB, Lam DK, Blanas N, Clokie CM, Sandor GKB. Small mouths...Big problems? A review of scleroderma and its oral health implications. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007 Nov; 73: (9):831-6.

- Cooper GS, Miller FW, Germolec DR. Occupational exposures and autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002 Feb;2(2-3):303-13.

- DeLong L, Burkhart N. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. Baltimore, 2007.

- Gold LS, Ward MH, Dosemeci M, DeRoos AJ. Systemic autoimmune disease mortality and occupational exposures. Arthritis Rheum 2007 Oct; 55(10): 3189-201.

- Leader DM. Scleroderma and dentistry: every dentist is a scleroderma specialist. J Mass Dent Soc. 2007:56:2, pg 16-19.

- Sanford, Jr. TW, Peterson J, Machen RL. CREST Syndrome and Periodontal Surgery: A Case Report. J Perio 70:5, May 1999.

Forms of Scleroderma

Systemic form: This form affects most organs, producing fibrosis of the skin, heart, lungs, and kidneys.

- Diffuse scleroderma — extenstive skin indurations

- CREST syndrome includes calcinosis, Raynaud's syndrome, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasis.

Localized scleroderma (involving only the skin)

- Morphea is characterized by firm, hardened patches of skin.

- Linear scleroderma — located on midline of forehead

- En coup de sabre (cut of the sabre) is characterized by a localized thickened area of skin, appearing as a knife wound. Figure 4 shows an isolated area extending from the lip to the gingival tissues in a boy.

CREST syndrome

Several extraoral factors are visible in patients with systemic scleroderma (PSS) who exhibit the CREST syndrome.

• Calcinosis — Abnormalities in calcium metabolism causes a deposition of calcium salts in the tissues that is called calcinosis, and it may lead to thickening and tightening of the skin and the extremities. This causes the loss of some dexterity in the hands and may make it difficult for the patient to hold items such as toothbrushes and floss (see Figure 5).

• Raynaud's phenomenon — Raynaud's phenomenon is localized ischemia caused by spasm of the arteries (see Figure 6). The fingers and toes are most often affected and the condition may be idiopathic although it is often associated with scleroderma or other autoimmune diseases such as lupus erythematosus. Most patients with systemic scleroderma have Raynaud's phenomenon. The digital ischemia may be triggered by cold or emotional stress and is relieved by heat. The patient presented in Figure 6 was wearing gloves because her fingers are cold, dark pink or cyanotic, painful, and somewhat rigid. Raynaud's phenomenon can also affect the lungs by tightening the blood vessels.

• Esophageal dysmotility — The tightening of the mouth and esophagus progresses and may also cause GERD. Patients often exhibit hoarseness and wheezing; these may be the early signs of damage. Esophageal constriction is characteristic due to fibrosis and atrophy of smooth muscles.

• Sclerodactyly — Sclerodactyly is localized scleroderma of the digits (see Figures 5 and 7). The tightening of the skin's connective tissue may cause the fingers to become fixed in a distorted position, and the blood supply to the digits may be compromised to the point of causing ischemic necrosis of the tips as evidenced in Figure 5.

• Telangiectasia — Telangiectasia is permanent dilation of small blood vessels, presenting as red or brown pigmented spots on the skin. As seen in Figure 7, the patient has developed some pinpoint size evidence of telangiectasia. Depending upon the particular patient, the pigmentation may be slight or more extensive.

About the Author

Nancy Burkhart, RDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics at Baylor College of Dentistry and Texas A&M Health Science Center in Dallas. Nancy is also a co-host of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group through Baylor (www.bcd.tamhsc.edu/lichen). She is the coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist.