In 1974, the American Dental Association recommended that dental offices measure patients' blood pressure (BP).1 It was also one of the first things we learned in dental hygiene school. But the moment we step foot into the “real world,” we’re met with time constraints that lead us to believe we don’t have the time to check vitals.

With the challenges of patient compliance and lack of support from team members, it can become a nuisance. But as preventive specialists it is our duty to educate our patients on prevention in all areas of the body, not just the mouth.

The idea of hygienists saving lives can sound far-fetched until you start to understand the connection between the mouth and the body. When patients present with risk factors such as gum disease and hypertension, it increases their risk for heart disease.2-3 Heart disease is the number one cause of death in America.4

High blood pressure can lead to heart attacks, strokes, vision loss, kidney failure, and sexual dysfunction.5 Providing high-quality care starts with measuring vitals and a thorough medical history review. This gives us an opportunity to educate patients on the oral-systemic connection.

You may be your patient's only HCP in years

Although we measure BP when administering local anesthetic, this is not the only time patients should have their vitals checked in a dental setting. Many patients see their dentist more often than their primary care doctor.6 You could potentially be the only health-care provider a patient has seen in years.

You might also be interested in: Take your patients' blood pressure: It could save their life

Imagine a patient comes to the dentist for a cleaning but hasn’t been seen by their primary care doctor in 10 years. They list no medications and no known systemic conditions. You check their BP and it’s 180/110—now imagine if you hadn’t checked it. The fact that this patient has no known systemic conditions could very well be because they haven’t seen a primary care doctor. Hygienists carry the responsibility of collecting vital readings for the health and safety of their patients.

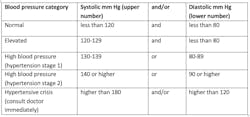

The ADA recommends patients with systolic pressure >180 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure >100 mmHg should be referred to their physician as soon as possible or sent for urgent medical evaluation.7 They have also laid out guidelines on how to accurately measure BP and how to navigate the different readings. Showing patients a simple chart like the one below can help them understand their BP reading.

Adapted from "Understanding blood pressure readings" from the American Heart Association

Challenging, but not impossible

The lack of support, time, and patient compliance can make this challenging to implement. But it’s not impossible! When seeking a new position, address vital readings at the interview. Ask how the office implements this practice. If the office has yet to adapt to this standard, suggest making a change and explain how it benefits the patient.

I find that the best time to take vitals is when opening the cassette and setting up for a procedure. If that timing doesn’t work, you could do it while beginning your clinical notes. There are countless opportunities for us to provide patients with a service that could potentially save their life. Explain to patients that heart health is linked to oral health8 and that hypertension is known as the silent killer because there are no signs or symptoms.9 Review that we also want to make sure vitals are within normal limits to avoid any potential medical emergency. Taking the time to educate patients about the “why” will increase patient compliance.

More than 30 years after their initial recommendation, in 2006 the ADA again encouraged dental offices to measure blood pressure.1 It’s long overdue for hygienists to adapt to this standard. Advancing our profession starts with hygienists who are willing to implement change. Being a prevention specialist means breaking legacy errors,10 starting with providing our patients with hypertension screenings. Every patient, every procedure, every time.

References

- Yarows SA, Vornovitsky O, Eber RM, Bisognano JD, Basile J. Canceling dental procedures due to elevated blood pressure: Is it appropriate? J Amer Dent Assoc. 2020;151(4):239-244. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2019.12.010

- Karnoutsos K, Papastergiou P, Stefanidis S, Vakaloudi A. Periodontitis as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: The role of anti-phosphorylcholine and anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Hippokratia. 2008;12(3):144–149.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart disease and stroke. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/heart-disease-stroke.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart disease facts. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm

- American Heart Association. Consequences of high blood pressure. Accessed February 18, 2023. https://www.heart.org/-/media/files/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/consequences-of-high-blood-pressure-infographic.pdf

- Smith HA, Smith ML. The role of dentists and primary care physicians in the care of patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Front in public health. 2017;5:137. doi:3389/fpubh.2017.00137 Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- American Dental Association. Hypertension (high blood pressure). Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/hypertension

- Shmerling RH, M. D. Gum disease and the connection to heart disease. Harvard Health. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/gum-disease-and-the-connection-to-heart-disease

- S. Food and Drug Administration. High blood pressure–understanding the silent killer. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/special-features/high-blood-pressure-understanding-silent-killer

- Strange M. Legacy errors: Why do we normalize not-so-great behaviors in the dental industry? Accessed February 18, 2023. https://www.rdhmag.com/infection-control/article/14281399/legacy-errors-why-do-we-normalize-notsogreat-behaviors-in-the-dental-industry