We have an ethical responsibility to do this before administering anesthesia

By Laura Webb, RDH, MS, CDA

Recently, a reader contacted me to discuss concerns she had about working as a relief dental hygienist in environments where she was expected to provide local anesthesia for the dentist's patients, but where no health history review or current physical assessments had been recorded by the dentist or dental assistant. She indicated that this was a far more common issue than we might realize.

We are educated in dental hygiene school to review the health history, provide physical examination, visual observation, and psychological evaluation to assess our patient's ability to tolerate care. This has always been an absolute prerequisite for provision of care. It is particularly important that these assessments are carefully conducted before each appointment when local anesthesia is to be administered in order to properly determine the agent, dose, and techniques to be employed.

As discussed in my RDH magazine columns in January and April 2016: although local anesthetics are remarkably safe at therapeutic doses, we must consider existing conditions and medications that may precipitate adverse effects and make the appropriate modifications in treatment.1,2

Update Health History Forms

Typically patients complete a comprehensive health/dental history form prior to initial treatment at the dental facility. The forms usually include identification of medical conditions, prescription medications, over-the-counter products (including herbal forms), attitudes, previous dental office experiences, and experiences with local anesthetics. The dental hygienist must be able to fully understand the information and query the patient for clarification, as needed, to facilitate the planning for safe care.

The questionnaire should be updated regularly to reflect current concerns in general medicine and dentistry. However, there is no legal requirement for filling out a completely new health history.3 As a rule, the dental hygienist need only fully update the information and record it in the chart.4 Sometimes a supplemental form is used that is signed and dated by both the patient and the clinician. At every appointment, the patient should be asked about:

1. Changes in general health

2. Current conditions being treated by a physician

3. Current drugs, medications or over-the-counter products

Physical assessments-Patients may not be aware of their current health status or may not wish to share it. Therefore, in order to promote patient safety, it is important that measurement of vital signs is performed.4,5 Dental hygiene textbooks are a good resource for detailed descriptions of the procedures.

Vital signs can assist us in identifying conditions requiring modifications in treatment and also provide baseline values that may be needed for comparison during treatment or in the event of a medical emergency. 5,6,7 Vital signs that should be measured routinely prior to provision of local anesthesia include:

1. Blood pressure

2. Pulse

3. Respiration

4. Weight

Blood pressure, pulse, rhythm, and respiration rates provide information regarding the functioning of the cardiovascular system.6

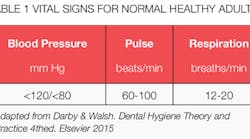

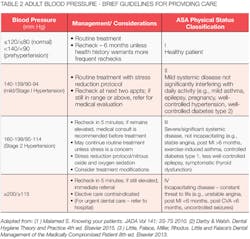

Local anesthetics typically elevate blood pressure, particularly for anxious patients, which makes determination of baseline data important. See adult blood pressure values in Table 1. Brief Guidelines for Adult Patient Management related to blood pressure are described in Table 2.

We most commonly assess pulse (heart rate) at the radial artery. The rate is evaluated for a minimum of 30 seconds and then converted and recorded as beats per minute. The rhythm is described as regular or irregular and the quality of the pulse as thready, weak, bounding, or full. Heart rate may be influenced by exercise, body temperature, anxiety, medications, positioning, blood loss, and pulmonary conditions.5 See adult pulse rate values in Table 1.

Respiration rate may be taken before or after the pulse rate. Respiration rate may change when the patient is aware that you are taking it. Leaving your fingers on the radial artery during evaluation of respiration is a good strategy as patients think that you are assessing the pulse. Respirations should be described as irregular, normal, shallow, or deep. Recall that hyperventilation is not unusual in the dental setting, particularly with anxious patients. See adult respiratory rates in Table 1.

Accurate weight determination is important for calculating maximum recommended dose (MRD) for local anesthetic agents. Lowering the MRDs for children, medically complex patients, and older patients should be considered as, for these populations, biotransformation of local anesthetics may be slower, putting them more at risk for an overdose.

Sometimes the health history review or the physical assessments will indicate that other tests are required prior to patient treatment.

Visual observation-Health status and anxiety can also be assessed through visual observation of the patient. Their posture, gait, speech, and skin can provide clues to unidentified disorders.

Psychological evaluation-As mentioned earlier, health/dental history forms usually include questions about attitudes and previous dental experiences. It is important to identify anxious patients so that we can provide stress reduction protocols as outlined in my April 2016 RDH column.2 Vital signs may increase in individuals who are stressed, and their pain threshold may be lowered.5

Assessment of risk-We use the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification system to assist us in assigning risk (Table 2). These are considered general guidelines and require that we employ our best professional judgment regarding their use. We should also consider type, severity, and control of the patient's medical conditions. The dental team and the medically complex patient's physician can be valuable to consult when determining risk and treatment planning. Table 2 represents a brief compilation of expert opinion regarding decision-making related to blood pressure values and ASA status. Note: blood pressure categories/cut-offs vary in the literature. Frequent review of the literature to identify updates in protocols is recommended.

Providing local anesthesia safely is our ethical responsibility and relies on thorough patient assessment prior to treatment. Since health status frequently changes, we must carefully review the medical history, provide physical examination, visual observation, and psychological evaluation at the beginning of every appointment to assess the patient's ability to tolerate care. RDH

References

- Webb LJ. Dental anesthesia: Overview of injectable agents useful for nonsurgical periodontal therapy. RDH Magazine. Jan 2016 Vol 36 No 1. Reprint OHASA Journal. 1st Quarter 2016 Vol 17 No 1.

- Webb LJ. Anesthesia for older adults: Local anesthesia facilitates aggressive perio treatment. RDH Magazine. Apr 2016 Vol 36 No 4.

- Glasscoe-Watterson D. Medical history update dilemma. RDH Magazine. Feb 2009 Vol 29 No 2.

- Malamed S. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2013.

- Logothetis DD. Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017.

- Malamed S. Knowing your patients. JADA. May 2010. Vol 141 S3-S7.

- Little J, Falace D, Miller C, Rhodus M. Little and Falace's Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 8th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2013.

LAURA J. WEBB, RDH, MS, CDA, is an experienced clinician, educator, and speaker who founded LJW Education Services (ljweduserv.com). She provides educational methodology courses and accreditation consulting services for allied dental education programs and CE courses for clinicians. Laura frequently speaks on the topics of local anesthesia and nonsurgical periodontal instrumentation. She was the recipient of the 2012 ADHA Alfred C. Fones Award. Laura may be contacted at [email protected].