Restorative contours sometimes challenge hygienists

By Chris Salierno, DDS

In the attempt to restore broken teeth or replace ones that are missing, restorative dentistry may introduce contours that are not found in nature. These unnatural contours can have adverse effects on the periodontium and surrounding teeth.

Common examples include amalgam and composite resin restorations that “overhang” into the interproximal area. Overhangs are detrimental not only because they trap plaque and calculus, but they also often make hygiene procedures more difficult. Dentists and hygienists commonly advocate attempting to polish the overhang away or replacement of the restoration to avoid complications.

The pontic of a fixed partial denture also creates unnatural contours for the oral environment. The edentulous ridge is covered by the prosthesis in one of several designs, including hygienic, full ridge lap, modified ridge lap, and ovate.1 Each of these designs presents unique hygienic challenges for the patient as they may impede the removal of the plaque and calculus which accumulate underneath the pontic.2,3

Dental implant restorations can also introduce contours that prove problematic for hygiene. Although implant components are not at risk for dental caries, the literature has clearly established that plaque and calculus can lead to peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis.4 While studies have identified risk factors for peri-implant disease to include parameters such as tobacco use and radiation therapy,5 the various and unique contours sometimes adopted by the restorations has yet to be examined. Although comparisons may be drawn to the contours of pontic designs, the presence of a transmucosal abutment and peri-implant sulcus add surface area that is challenging to maintain.

This article proposes three categories of implant restoration contours: anatomical emergence, modified ridge lap, and full ridge lap. Each group presents unique challenges in hygiene maintenance for both the patient and the hygienist. The categories do not represent a formal classification but rather are meant to serve as a guide for vigilant dentists and hygienists. Research will be required to further organize the various topographies of implant restorations and their clinically-relevant effects on plaque retention and ease of home care. Additional parameters to be considered in more detailed classifications include, but are not limited to, the differences in implant number and proximity, restorative material, and implant sulcus depth.

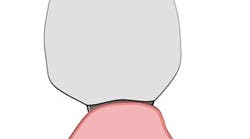

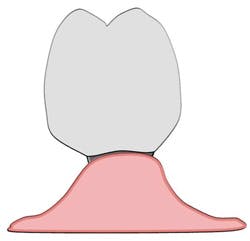

Anatomical emergence

An anatomical emergence represents a prosthetic and surgical achievement. The implant has been placed in a three-dimensional, prosthetically-driven manner so that it closely resembles the orientation of the root which once occupied its location in bone. The transmucosal abutment emerges from the gingiva and is continuous with the crown it supports (see Figure 1). The maintenance procedures of a single implant with anatomical emergence contours may resemble the procedures used for a natural tooth with an anticipated high degree of success. Plaque and calculus accumulate in the implant sulcus only as there are no retentive areas created by the transmucosal abutment and crown (see Figure 2).

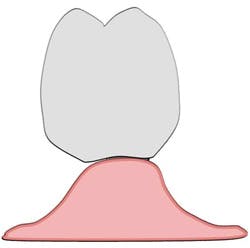

Modified ridge lap

A modified ridge lap may give a clinical appearance that resembles an anatomical emergence (see Figure 3). However, upon closer inspection, a modified ridge lap is found to be present when there is a noncontinuous emergence of the transmucosal abutment into the crown and that degree of discontinuity is 90 degrees or greater (see Figure 4). An obtuse angle of emergence introduces a convexity between the crown and the gingiva which will trap plaque similarly to that of a modified ridge lap pontic for a fixed partial denture (see Figure 5).

The prosthetic need for a modified ridge lap occurs when an implant is unable to closely resemble the size and/or position of the root which it has replaced. Common causes of the implant-root discrepancy include implants placed off-axis (too far palatally, for example) and implant diameters that are narrower than the original root. These discrepancies are abruptly realized as the transmucosal abutment emerges from the gingiva and must quickly adapt to the correct tooth position. Gingiva that would normally be exposed to the oral environment is now covered by the contours of the crown. Plaque and calculus accumulate in the implant sulcus and along the area where the crown and gingiva meet. Due to the convex nature of the crown in this area, plaque and calculus are removed with greater difficulty than a system with anatomical emergence contours.

Modified ridge lap contours are often found with molar implants. While an implant may roughly resemble the shape of a single rooted tooth, it bears little resemblance to the shape of a multi-rooted molar tooth. As such, it is common to see the transition from a circular implant to a wide molar occur suddenly as the transmucosal abutment emerges from the gingiva (see Figure 6).

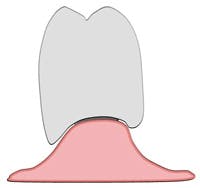

Full ridge lap

A full ridge lap is typically evident clinically (see Figure 7). It exists when there is a noncontinuous emergence of the transmucosal abutment into the crown and that degree of discontinuity is less than 90 degrees (see Figure 8). An acute angle of emergence introduces a concavity between the crown and the gingiva which will trap plaque similarly to that of a full ridge lap pontic for a fixed partial denture (see Figure 9). The “flange” of restorative material hinders the hygienist and patient from removing plaque and calculus.

A full ridge lap is utilized by a restoring dentist to compensate for poor implant position and implant-root size discrepancies, as is the case with modified ridge laps. The laboratory may choose to fabricate the final crown contours with concave angles of emergence even though convex angles could be used effectively in certain cases. However, there are cases when a dentist and laboratory deliberately select a full ridge lap contour for esthetic reasons at the sacrifice of hygienic access.

A patient presented for restoration of an implant replacing tooth No. 4. It was immediately evident that the implant had been placed too coronal (see Figure 10). After an impression, the laboratory fabricated a screw-retained, porcelain-fused-to-metal implant crown. The laboratory was instructed to create full ridge lap contours so as to conceal the metal of the abutment and platform from being visible. At a try-in visit, the metal of the abutment and platform was still clinically visible (see Figure 11). Additional porcelain was added by the laboratory for esthetic purposes, which unfortunately added greater concave surface area to serve as a plaque trap (see Figure 12). The final restoration, when viewed clinically, achieves the desired esthetics at the sacrifice of ease of hygiene access (see Figure 13).

Home care options on the horizon

A promising option for these patients is oral irrigation therapy. One study has shown that oral irrigation with 0.06% chlorhexidine solution was more effective in reducing plaque and gingivitis compared with traditional rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine.6 It may be postulated that this effect is due to the ability of oral irrigators to penetrate deep into periodontal pockets — on average about 50% of the existing depth.7 Although these studies were done on natural teeth and not implants, we may still choose to extrapolate that oral irrigation offers advantages for implant maintenance as well. Future studies may confirm that different shapes of irrigator tips are better suited than others for negotiating the prosthetic contours discussed in this article. RDH

Chris Salierno, DDS, is a general dentist from Long Island, N.Y. He graduated from Stony Brook School of Dental Medicine in 2005 and completed a GPR there in 2006 focusing on implant prosthetics. While in dental school, Chris served as the national president of the American Student Dental Association. Currently, he serves as vice president of his local dental society and is vice chair of the American Dental Association’s New Dentist Committee. He lectures internationally on clinical dentistry, practice management, and leadership development. His material can be viewed online on his blog, “The Curious Dentist.”

References

1. Masterton JB. Recent trends in the design of pontics and retainers. Dent Pract Dent Rec 1964; 15:131-139.

2. Cavazos E. Tissue response to fixed partial pontics. J Prosthet Dent 1968: 20:143-153.

3. Liu CL. Use of a modified ovate pontic in areas of ridge defects: a report of two cases. J Esthet Restor Dent 2004; 16:273-281.

4. Luterbacher S, Mayfield L, Bragger U, Lang NP. Diagnostic characteristics of clinical and microbiological tests for monitoring periodontal and peri-implant mucosal tissue conditions during supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). Clin Oral Implants Res 2000; 10:521-529.

5. Karbach J, Callaway A, Kwon YD, d’Hoedt B, Al-Nawas B. Comparison of five parameters as risk factors for peri-mucositis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009; 24:491-496.

6. Felo A et al. Effects of subgingival chlorhexidine irrigation on peri-implant maintenance. Am J Dent 1997; 10:107-110.

7. Eakle S et al. Depth of penetration into periodontal pockets with oral irrigation. J Clin Periodontol 1986; 13:39-44.

On Wednesday, Aug. 1, Dr. Salierno, the author of this article, teams up with Dr. Scott Froum and Rebekah Duffy, RDH, to present a course at RDH Under One Roof titled, “Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Implant Complications: A Hygienist’s Role.”

The course presenters said, “With proper training and education, the dental hygienist can become an essential member of the implant team and can often become a major reason why patients accept dental implant care. In addition, the long-term success of implant dentistry is dependent on the maintenance role taken by the hygienist and the ability of the hygienist to act as ‘first-responders’ when implant complications arise.”

For more information, visit www.rdhunderoneroof.com.

Past RDH Issues