Dispelling old myths and discovering the hopes for those with hepatitis C

BY HEIDI EMMERLING MUÑOZ, PhD

"You have hepatitis C."

Those words turned my life upside down. I tell this story not to elicit sympathy but to illustrate what it means to live with hepatitis C (HCV): the physical as well as the emotional. Only now, because I am out of clinical hygiene and because there is a cure in sight, do I feel safe in telling my story.

I also tell this story to urge screening and to give hope to anyone living with HCV.

Diagnosis

Although this was only a routine well check and I was asymptomatic, I had three risk factors that caused my physician to order the screening:

• I was born in 1961.

• I was involved in clinical dentistry for many years.

• I had a blood transfusion in 1987.

The American Liver Foundation recommends baby boomers (born between 1945 and 1965) and recipients of blood transfusions prior to 1992 be screened because these populations have likely exposure before HCV was discovered. Health-care workers should be screened due to possible occupational exposure.

CDC statistics indicate more than 3 million people in the United States are infected with HCV, most being asymptomatic. Therefore, 75% of the people are undiagnosed. Although the virus itself does not kill people directly, it can attack the liver. Twelve thousand people per year die from HCV-related liver disease. The CDC states out of every 100 people who become infected with HCV, 75 to 85 will acquire a chronic infection, 60 to 70 will develop chronic liver disease, 5 to 20 will develop cirrhosis, and one to five will die of cirrhosis or liver cancer. According to the CDC, 17,000 Americans per year become infected with HCV.

In light of these potentially serious consequences - combined with the fact that in October the FDA is expected to approve a breakthrough treatment that is easily tolerated and boasts a 95% cure rate - now more than ever people should get tested (see sidebar: Diagnostics).

Treatment

The anticipated new treatment has people cheering. Until now, treatments have been poorly tolerated and ineffective. Back when I was diagnosed, I got the feeling my physician would have preferred to deliver a death sentence. It must have been difficult telling me that Rebetron (ribavirin and interferon) was agonizing and I might not be able to tolerate this chemotherapy. And, with only a 30% cure rate, more than likely it wouldn't work. But it was the best we had, and he was convinced I should undergo this treatment, so I did (see sidebar: Vaccine and Treatment Timeline).

"Poorly tolerated" does not begin to describe the side effects experienced by most. Many are unable to complete it. Most have to forego work. What lay ahead was a 48-week sentence of self-administered interferon shots three times a week with the resultant chemotherapy side effects.

Some describe this as having the worst case of the flu imaginable every single day for a year. Another describes it as feeling 90 years old: fatigue, bone-chilling aches, anxiety, depression, nausea, diarrhea, and mental fogginess. Additionally, during treatment, I came to lose most of my hair and half of my body weight. I also became a human pin cushion; in addition to self-injections, I had blood drawn every month to check my viral load and CBC to make sure the treatment was suppressing the virus and to make sure I would not become anemic - another gift from ribavirin. Unfortunately, I would not be one of the lucky few for whom this torture would pay off. After 48 weeks of agony, I was back in my original predicament: living with the infection, the stigma, the worry.

Stigma and Transmission

The pain of treatment was nothing compared to dealing with the stigma. People often assume those with HCV are ignorant, dirty, undesirable, or promiscuous. I faced financial consequences and emotional repercussions from others who were ignorant and misinformed.

When I should have been focusing on my healing, I was worrying about the only livelihood I ever had: dentistry. Would my HCV status preclude me from working? According to my physician, the American Liver Foundation, and the CDC, the answer is a resounding no. According to the CDC, there have been no reports of an HCV transmission from an infected dental health-care professional to a patient in a dental health-care setting.

All health-care personnel, not just those who are HCV-positive, should follow strict aseptic techniques and standard precautions. Molinari and Cuny reiterate, "Adherences to standard precautions are considered adequate in controlling the spread of HCV from worker to patient. No work restrictions are recommended for HCV-infected health-care workers."

The main work restriction for HCV is tolerance to therapy rather than the virus itself. I could not afford to stay home and convalesce, which would have been ideal. While undergoing chemotherapy, there was a spike in sick days. There were days I simply couldn't get out of bed or couldn't complete the day. I needed more time off for doctor appointments, more frequent breaks, less time with patients. I continually requested more administrative work and less clinical work.

Unfortunately, the nature of dental hygiene provides little flexibility here. Obviously, my paycheck took a hit after I had exhausted my sick days. Additionally, I had to back out of commitments because I did not have the stamina or focus. Between the cost of treatment, a divorce, and significant loss of work, the financial hit was so hard, I faced another stigma: bankruptcy. Today, for a variety of reasons (a few related to HCV, most not), I have chosen not to renew my RDH license. For information on how I transitioned out of clinical dental hygiene, read "Help, Let Me Out!" in the May 2014 issue of RDH.

In addition to work difficulties, my personal life disintegrated. I felt a sense of shame as I listened to a friend unwittingly joke how Pamela Anderson was repulsive. Not because of her famously exaggerated cup size, but rather (and solely) because she had the misfortune of contracting HCV. Within a month of my diagnosis, my husband asked for a divorce. My worries about my health, the agony of treatment, financial devastation, losing friends and my husband: would I ever be able to crawl out?

Fortunately - no thanks to Hollywood and society perpetuating negative stereotypes - things got better. One ray of hope was meeting a man who would later become my husband. I awkwardly divulged my status, which went better than I'd expected.

But then we happened to watch the movie Bewitched. In one scene, Person A is flirting with Person B, but Person C (who is a witch) likes Person A and uses powers to make Person B involuntarily blurt out to Person A that she has HCV, presumably inferring HCV makes one sexually undesirable. Laughs ensued but he and I sat there silent, embarrassed, and angry. The president of the American Liver Foundation later said about the movie: "Tragically, this remarkably tasteless comment plays into the stigma that many people with hepatitis C have to cope with every single day ... I can't imagine anyone in Hollywood making a joke about HIV infection, for example, but because the public is so uneducated about hepatitis C, it apparently seems acceptable to trivialize the disease in a comedic context, at the expense of millions of hepatitis sufferers."

"The Simpsons," "Family Guy," "American Dad," and many other shows and movies have used HCV as a tasteless punchline.

The CDC reminds us that HCV is spread through percutaneous exposure, not monogamous sex, kissing, hugs, and so forth. Of course, there are "spicier" sexual practices that could encourage the transmission of HCV. According to the CDC, people in short-term relationships, people with multiple partners (including sex workers), people with HIV co-infections, and male couples comprise the bulk of the < 3% of HCV cases thought to be transmitted through sex. CDC statistics indicate people with HIV co-infections are the main basis for this number; others who round out this number are people who use drugs with sex (raises pain threshold and duration which increases likelihood of trauma), partners with genital lesions, those who engage in anal intercourse or rough sex that might result in mucosal tears, those who use certain sex toys, and those who engage in sex during menstruation. The common denominator here is the risk for blood-to-blood exchange. Even though the numbers are low, people in this "spicy" category should consider a condom or barrier during sex as a preventive measure (CDC).

Those more vanilla people who are in long-term, monogamous, heterosexual relationships comprise <0.6% of HCV cases thought to be sexually transmitted. Many scientists dispute that number, claiming there is zero sexual transmission, and that those few cases should more accurately be attributed to cocaine use (nasal mucosa trauma) during sex or the sharing of contaminated personal care items (razors, clippers, tweezers, toothbrushes, etc.) as people sharing a household tend to do.

Therefore, national organizations do not recommend condom use or change in sexual practice for HCV cases who are in long-term monogamous heterosexual relationships (Terrault et al., Tohme and Holmberg, and Vendelli et al.). Oral sex is also considered a no-risk behavior for transmission of HCV (CDC).

To put things into perspective, compare the rate of vertical transmission (HCV-infected mother to child during childbirth) to sexual transmission. Traditional sexual behavior produces less blood than childbirth. Not surprisingly then, the data from national organizations show that the rate of sexual transmission is lower than vertical transition. According to the CDC, the rate of vertical transmission is < 5%, the rate of "spicy" behavioral is <3%, and the rate of "vanilla" behavioral is <0.6%.

A case in point is that, unbeknownst to me, after my blood transfusion with the birth of my first child, HCV was circulating for almost two years and my viral count was probably in the millions when my second child was born. In spite of this, he is HCV-negative. No one was surprised when both my current husband (yes, he hung around) and the father of my children with whom I was intimate prior to knowing my HCV status, were both negative for the virus as well.

Despite these findings and repeated reports from national organizations, too much misinformation persists, including within our own professional articles and CE presentations that exaggerate the rate of HCV sexual transmission. If people in the health-care industry are misinformed, how should HCV patients expect friends or lovers with no medical background to understand?

Because intimacy plays such a significant role in one's well-being, friendship and sex should not be a source of angst; HCV sexual transmission is not widely accepted by the experts. Since HCV is blood-to-blood transmission, there is usually not enough blood or open lesions involved in traditional sexual practices to efficiently transmit the virus. By being a source of information, not misinformation, we can make a real difference for people with HCV.

Risk Factors

I was a health-care worker. Although there were no apparent percutaneous incidents, I was a dental assistant in the 1970s when it was the norm to throw everything in what we used to call "cold sterile" and to not wear gloves, masks, or eye protection except in the rare case when a patient disclosed a communicable disease. During this early stage of my career, I had no formal training and was unfamiliar with how to protect myself from occupational exposure.

Later, I worked as a dental hygiene instructor in a clinic. Working in a clinic - especially in an academic environment - presents a number of opportunities for occupational exposure. First, clinic clients often present as heavy bleeders and with compromised medical conditions. The large numbers of at-risk clients being treated simultaneously can create significant blood spatter, especially with many ultrasonics operating at the same time. Additionally, there could be breaches with sterile technique since the students are new to these practices. Though unlikely because there were no percutaneous incidents, there is a small possibility that I could have been at risk of contracting HCV at work. All health-care workers should be screened, especially if there was a percutaneous incident.

Depending on the setting, tattoos and piercings are identified risk factors because they involve blood, needles, and breaking the skin. I have four (amazing, award-worthy) tattoos. However, my tattoos were done in a clean, commercial studio that was recommended by a dermatologist. I came to know my world-famous tattoo artist prior to getting inked and observed the sterile practice, including the use of my new needles being removed from the package.

According to the CDC, there is little evidence that HCV is spread by getting tattoos in licensed, commercial facilities. Any transmission of HCV via tattoo needles is likely from unlicensed facilities where sterile practice is inconsistent at best, such as in garages, prisons, in someone's kitchen, under the influence of alcohol, etc.).

By far, the most likely risk factor for me and anyone else with an existing HCV infection is having had a blood transfusion prior to 1992. Mine was in 1987 during complications with the birth of my first child. The medical community had not heard of HCV at that time; there was only A, B, or non-A, non-B. Therefore, there were no means to screen for HCV. Transfusions or organ transplants prior to 1992 is how approximately 90% of most HCV cases were initially exposed. Because we have identified the virus and blood is now screened, the risk of acquiring HCV from a transfusion post 1992 is virtually nil.

Outcomes

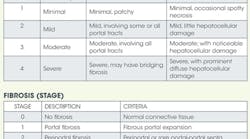

My physician convinced me I would die if I did not endure the treatment - crude by today's standards, but state of the art at the time. While treatment got rid of the virus during treatment, it returned post-treatment. Thus, I am a termed a "relapser" with "failed" treatment. I have the most common and resistant genotype: 1 A. After I was deemed a relapser, my physician sent me to a gastroenterologist (GI), a true gift. My GI acknowledged to me the available therapy was inappropriate for my case because I was, and still am, asymptomatic, plus the biopsy showed barely Stage I (no scarring) and no inflammation.

My GI assured me I would probably die of old age before I had any problems with the virus. After all, if I indeed contracted it in 1987 and was just now barely showing Stage I, this was a very slowly progressing condition. Balancing the relatively minimal risk of HCV progressing to liver cancer (1%-5%) with the ordeal and stress of the therapy, he said if he were the patient, he would not have opted for the therapy. He even told me to "quit being so pure ... have a little wine once in a while" and to throw away my "herbs and spices." He obviously didn't get the memo that dental hygienists can sometimes go a little overboard. Besides giving me permission to drink (not the whole bottle, and not every day or even every week), he also predicted there would be a cure long before I ever experienced symptoms. The reason? He believed that money would fuel the research for a cure for a disease afflicting baby boomers.

He was just what the doctor ordered. The most important thing he did was get me to relax and view my situation through the lens of reality rather than fear. Although we should not be cavalier and reckless when facing a potentially life-threatening disease, laughter and joy are essential components in overall health and healing. It has been said that gifts come in unexpected packages, which is how I now view my HCV diagnosis. HCV gifted me a needed financial, personal, and professional reboot I would not have otherwise sought. It gave me the permission and strength to say "no, thank you" to things not in my best interest. I have also gained knowledge and the opportunity to share that knowledge with others. My life is more balanced as I take a more holistic approach (see sidebar: Living with HCV).

The balance in my life has yielded positive results. HCV is still present with a high viral load, yet the disease has not progressed. This is great news because my GI's prediction of a cure has come true. Last year brought less toxic and more effective regimens than my original treatment. Currently, the treatment is one shot per week of interferon instead of three; the course of treatment is 12 weeks instead of 48; the efficacy is 80% instead of 30% for genotype 1A. It gets even better. In October 2014, the FDA is expected to approve an interferon-free therapy (no shots, no debilitating side effects), one pill daily for eight to 12 weeks and, best of all, a 95+% cure rate. I am truly grateful for all that this has taught me and for this new regimen, which I look forward to and am confident will eradicate the virus.

The odds are that someone you know has HCV. While millions are living with this and are leading rich, full lives, HCV is serious and needs to be managed - even for people who are asymptomatic. People with any degree of risk of contracting HCV should get screened; this means you too. Now that you are hip to hep C, be the inspiration my GI was for me. Consider it your personal and professional challenge to dispel the myths, stamp out the stigma, encourage screening, and share the news of the exciting new cure.

HEIDI EMMERLING MUÑOZ, PhD, is a professor of English at Cosumnes River College. Prior to her current position, Dr. Muñoz was interim director and professor of dental hygiene at Sacramento City College. She has written numerous articles and columns and is a frequent contributor to RDH. Dr. Muñoz can be reached at [email protected].

References

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)

American Liver Foundation (ALF)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Grewal P, et al. Hepatitis C: Treatment options and the patient experience. Webinar; In Hep C 1 2 3 Series; American Liver Foundation; May 28, 2014.

HCVAdvocate

Hepmag

Kaiser Permanente

Molinari J, Cuny E. Hepatitis: What every dental professional needs to know. DentalCare.com, Course #307 17; Aug 2007. Accessed June 1, 2014.

Terrault NA, et al. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among monogamous heterosexual couples: The HCV Partners study. Hepatology 2013; 57(3): 881-889.

Tohme R, Holmberg S. Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission? Hepatology 2010; 52.4. 1497-1505.

Vandelli C, et al. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among monogamous couples: Results of a 10-year prospective follow-up study. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2004; 99, 855-859; doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04150.x.

Web MD

Diagnostics

Blood tests associated with HCV

HCV antibody screens for infection and exposure to HCV. This test cannot distinguish between someone with an active or a previous HCV infection. The following tests may be used to diagnose a current infection and to guide and monitor treatment:

• HCV RNA test, qualitative is used to distinguish between a current or past infection. It is reported as a "positive" or "detected" if any HCV viral RNA is found; otherwise, the report will be "negative" or "not detected." Normal is a negative result.

• HCV viral load (HCV RNA test, quantitative) measures the number of viral RNA particles in the blood. These tests are often used before and during treatment to help determine response to therapy by comparing the amount of virus before and during treatment (usually at several time points in the first three months of treatment). Some newer viral load tests can detect very low amounts of viral RNA. Normal range is <615 IU/mL.

• Viral genotyping is used to determine the kind, or genotype, of the HCV virus present. There are six major types of HCV; the most common in the United States (genotype 1) is less likely to respond to treatment than genotypes 2 or 3 and usually requires longer therapy (48 weeks versus 24 weeks for genotype 2 or 3). Genotyping is often ordered before treatment is started to give an idea of the likelihood of success and how long treatment may be needed. Type 1 is the most common in the United States; type 2 and 3 are found worldwide; type 4 is in Africa; type 5 is in South Africa/Egypt; type 6 is in Asia.

Liver function tests

• Bilirubin. A brownish-yellow substance found in bile. It is produced when the liver breaks down old red blood cells. Bilirubin is then removed from the body through the stool (feces) and gives stool its normal color. When bilirubin levels are high, the skin and whites of the eyes may appear yellow (jaundice). Normal range is .2-1.2 mg/dL.

• Albumin. Made mainly in the liver. It helps keep the blood from leaking out of blood vessels. Albumin also helps carry some medicines and other substances through the blood and is important for tissue growth and healing. Normal range is 3.7-5.7.

• Prothrombin time (a measure of blood clotting). It may also be called International Normalized Ratio (INR). Prothrombin, or factor II, is one of the clotting factors made by the liver and the test is to determine how the liver is functioning. Normal range is 11.7-14.3 seconds.

Liver enzyme tests

• Alanine aminotransferase (ALT or SGPT) ALT is measured to see if the liver is damaged or diseased. Low levels of ALT are normally found in the blood. But when the liver is damaged or diseased, ALT is released into the bloodstream, which makes ALT levels go up. Normal range is 0-36 U/L.

• Aspartate aminotransferase (AST or SGOT) Low levels of AST are normally found in the blood. When the liver is diseased or damaged, additional AST is released into the bloodstream. The amount of AST in the blood is directly related to the extent of the tissue damage. After severe damage, AST levels rise in six to 10 hours and remain high for about four days. The AST test may be done at the same time as a test for alanine aminotransferase, or ALT. The ratio of AST to ALT sometimes can help determine whether the liver or another organ has been damaged. Both ALT and AST levels can test for liver damage. Normal range is 10-40 U/L.

Liver biopsy (NIH)

Liver biopsy is an out-patient procedure performed by quickly inserting and then withdrawing a 15- to 18-gauge needle into the liver. A successful biopsy obtains a piece of liver tissue approximately the diameter of the lead in a pencil and 1 inch long. This can be done with or without a topical anesthetic and/or an analgesic "cocktail."

Vaccine and Treatment Timeline

Vaccine

There is currently no vaccine but research is being conducted to develop one (WebMD).

Therapy timeline in brief (hvcadvocate unless noted otherwise)

1991-1997: Interferon (Intron A, Roferon, and Amgen/InterMune)

• How it works: Stimulates the system to fight off pathogens by interfering with viral replications. Unfortunately, they attack the body as well.

• Dose: 3 million units three times per week (self-administered injections)

• Length of therapy: 48 weeks

• Efficacy: 9% (genotype 1) to 30% (genotypes 2 and 3)

• Limitations: Interferon hyperstimulates the immune system and causes harsh side effects. Needs frequent injections because it does not last long in the body. Synthetic interferon (peg-intron) lasts longer and now generally replaces traditional interferon.

1998: Intron A plus ribavirin/Rebetron.

• How it works: Combines interferon/Intron A with ribavirin, a synthetic nucleoside analog which was thought to prevent HCV from replicating

• Dose: Intron A (see above) plus 800-1,200 mg ribavirin per day

• Length of therapy: 48 weeks

• Efficacy: 29% (genotype 1) to 62% (genotypes 2 and 3)

• Limitations: Ribavirin is ineffective when used alone

2001: Peg-intron/Redipen plus ribavirin/Rebetron (peg/riba).

• How it works: Combines ribavirin with synthetic interferon (peg-intron), which does not break down in the body as quickly as natural interferon, resulting in a more sustained viral suppression

• Dose: Peg-intron is 1.5 mcg per kg per week; ribavirin is 800-1,200 per day

• Length of therapy: 48 weeks

• Efficacy: 41% (genotype 1)-75% (genotypes 2-6)

• Limitations: Although approved by FDA, peg/riba for 48 weeks for treatment-naive subjects (no previous treatment) with HCV genotype 1 has been superseded by treatments incorporating DAAs (see below) and should not be used (AASLD).

2011: Boceprevir/Victrelis and telaprevir/Incivek. (Also known as DAA, triple therapy, response guided therapy)

• How it works: Protease inhibitors/direct-acting antivirals (DAAs); were used specifically for genotype 1a in combination with peg/riba, termed triple therapy (peg + riba + BOC or TEL)

• Dose: Regular peg/riba as above plus 750-800 mg 3 times per day

• Length of therapy: Varied since it is response guided therapy (RGT); general range was 24-48 for full treatment; many cases were shortened due to inability to tolerate treatment

• Efficacy: 50-80% cure (NIH and WebMD)

• Limitations: Although approved by the FDA for 24 to 48 weeks using RGT, this therapy is markedly inferior to the preferred and alternative regimens. These regimens are associated with their higher rates of serious adverse events (anemia and rashes, for example), longer treatment duration, high pill burden, numerous drug-drug interactions, frequency of dosing, intensity of monitoring for continuation and stopping of therapy, and the requirement to be taken with food or with high-fat meals (AASLD).

2013: Sofosbuvir/Sovaldi and simeprevir/Olysio (ALF)

• How it works: Sofosbuvir inhibits the enzyme needed to replicate the virus; it is the first interferon-free treatment (but only with genotypes 2 and 3). Simeprevir blocks a protein needed by HCV to replicate.

• Dose: Sofosbuvir is 400 mg per day; simeprevir is 150 mg per day

• Length of therapy: Sofosbuvir is 12-24 weeks; simeprevir is 24-48 weeks

• Efficacy: Sofosbuvir is 80-95%; simeprevir is 85-85% in genotype 1b

• Limitations: For genotype 1, sofosbuvir must be used in combination with peg/riba and combined with ribavirin for genotypes 1 and 2; simeprevir is not used for genotype 1a with certain mutations so testing should be done to assure patient does not have the mutation (Q80K) (AASLD).

October 2014: Anticipated sofosbuvir, ledipasvir combo therapy for genotype 1 (CDC)

• How it works: Ledipasvir, a replication complex inhibitor combined with sofosbuvir's nucleotide analog polymerase inhibitor. This interferon-free therapy may be given with or without ribavirin; however, according to the American Liver Foundation, the addition of ribavirin will not significantly increase the efficacy (Grewal).

• Dose: Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (90/400 mg) fixed dose combination orally once daily, with or without food (CDC)

• Length of treatment: 8 weeks for patients (and patients with prior relapse); 12 weeks for experienced (partial and null responders) and patients with cirrhosis (CDC)

• Efficacy: 95-100% (CDC)

• Limitations: Since the cost of sofosbuvir alone is $84,000, the combination will undoubtedly be more.

FDA maintains a complete list of viral hepatitis therapies that are approved for treatment of HCV. See http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForPatientAdvocates/ucm151494.htm Note: this does not include the treatment anticipated in October.

The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) have recently issued guidance on the testing, management, and treatment of HCV available at: http://hcvguidelines.org/.

Living with HCV

1. Find support. Physicians can recommend local support groups. Forums are also on the Internet. Patients are encouraged to look until they find one that feels right. Surround yourself with positivity. Avoid negativity and toxic people.

2. Stay healthy and avoid other diseases. HCV can result in lowered immunity. Make sure vaccinations are current. Patients not in a long-term monogamous relationship should consider using a condom to prevent acquiring any new infections.

3. Get plenty of rest. Strive for 8-10 hours a day. Insomnia and fatigue are both effects of HCV and the therapy. Get on a good schedule, take warm baths, avoid caffeine. Get checked for sleep apnea. For more information, read "Catch some ZZZs" in the March 2014 issue of RDH.

4. Avoid alcohol and drugs. These all tax the liver. Be careful of Tylenol, certain herbal therapies, and tobacco as well. While no one with HCV should drink regularly, some experts say an occasional glass of wine with a nice dinner is fine and can help with relaxation.

5. Exercise, meditate, do yoga. These help combat anxiety, depression, and fatigue, which are often complications of the virus and the treatment. These also help maintain an ideal body weight, which is important to a healthy liver.

6. Eat well. A plant-based diet is ideal; fruits and vegetables help cleanse the liver; fat and iron tax the liver.

7. Be stingy with your personal care items. This not only prevents transmission of HCV, it also helps people with HCV (who have lowered immunity) from contracting other illnesses. Care items include razors, facial and body scrubbers, manicure items, toothbrushes (and toothpaste since the brush often contacts the tube), makeup and applicators, tweezers, hair combs/brushes/ornaments.

8. Learn all you can about HCV and your options. National organizations, support groups, health-care professionals, books, magazines.

9. Explore holistic health options. In particular, read "Holistic Approaches to Chronic Disease" in the August issue of RDH.

Past RDH Issues