Progress notes have been called many names and have taken many forms. The goal is to address, for the record, all critical areas encountered during dental treatment.

by Diana J. Lamoreux, RDH, MEd

Progress notes impact the quality of care and must be defensible in a court of law. Well-written records are tedious and time-consuming — a bane for hygienists. We understand good documentation monitors patient treatment and ensures quality care, yet we struggle with committing the time and thought. Composing progress notes is a dilemma for all, but utilizing a different method will be more efficient and accurate.

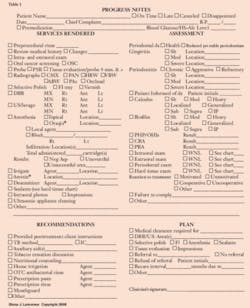

Instead of writing narratives, a checklist is substituted — boxes are marked adjacent to pertinent descriptors (see Table 1). Selections are readily available for all categories, whether it be services rendered, assessment, recommendations, or treatment planning. Gone are the days of longhand records and the process of writing out “medical history review, intra- and extraoral examination, cancer screening, debridement, selective polish,” etc. With a simplified format, hygienists will no longer dread the task or be tempted to shirk responsibility.

The initial incentive for developing the checklist was purely selfish. I was tired of the time commitment; but I also lacked confidence in our dental records, feared omissions, and the relentless threat of complacency.

Given the demanding schedules, dental professionals do forget to make entries or eagerly seek shortcuts. Such limitations cause a distrust of our own records; poorly written progress notes make hygienists feel vulnerable (pity the professional whose substandard documentation negatively impacts care or a lawsuit!). On the other hand, if well done, the recorded information provides invaluable reminders for future appointments.

Shortly after developing the checklist, I shared my new method with other hygienists. Two distinct perspectives surfaced — progress notes as a necessary evil vs. progress notes as a priceless resource. Most hygienists certainly acknowledge the importance but continue to fight the reality. Some express a fatalistic attitude, accepting the task due to a lack of choice. Regardless of the viewpoints, a consensus is apparent; they are dissatisfied with the past methods of record-keeping and are willingly embracing the prospect of a future option.

With the checklist customized to suit any practice, or serving as a bridge to computerization, reliance on total recall is no longer necessary. The beauty of such a form is the cuing it offers: The hygienist is now reminded by prompts on the list. Cues reduce the risk of omissions and oversights and save valuable time. Progress notes written longhand and strictly from memory are rarely all-inclusive or error-free.

Such a user-friendly format has three obvious advantages:

- Documentation is expedited

- Clinician confidence is elevated

- The quality of notes and patient care is improved

For calibration purposes, it is necessary to explore how past documentation practices correlate to the proposed checklist. Progress notes have been called many names and have taken many forms. Some schools and practices follow the SARP (Services Rendered, Assessment, Recommendations, and Plan) format; others use a SOAP system (Subjective Information, Objective Information, Assessment of Objective Information, and Plan).

Regardless of which system is used, as long as all critical areas are addressed and accurate, the legality of progress notes is (ideally) guaranteed. It’s certainly easier said than done when depending purely on memory!

SARP-style progress notes will serve as the example in this discussion. As various components are itemized below, compare with the selections on the checklist. Each category contains all descriptors needed to successfully and briefly complete documentation. When correlating the checklist to the descriptors, note that longhand notation is still required (in some areas) for individualization.

“S” or Services rendered — Preprocedural rinse type, intra- and extraoral examination, cancer screening, medical history review, probing, type and amount of anesthesia, areas of debridement, selective polish, fluoride type, radiograph type, impressions, lavage, sealants, and chemotherapeutics.

“A” or Assessments — Periodontal type, calculus and biofilm description, intra- and extraoral examination deviations, gingival assessment, clinical attachment loss and probing depth range, hard tissue chart deviations, updates and changes, patient reaction to treatment, and indices and risk assessments.

“R” or Recommendations — Oral self-care details, auxiliary aids introduced, nutritional or tobacco counseling, home and posttreatment recommendations, and prescriptions.

“P” or Plan — Debridement plans for the future, selective polishing, tissue evaluation appointment, impressions, sealants, areas to be re-evaluated and/or monitored in the future, referrals, recare interval and rationale, and medical clearance issues.

Given the choice between former narrative progress notes vs. simply marking boxes, the labor-intensive procedure is replaced with a helpful tool. No more dreading, omitting, wondering, doubting, compromising! This checklist method reduces mistakes and the time dedicated to the task, eliminates omissions and boosts operator confidence. Hygienists can now wholeheartedly depend on documentation, consistently offer excellent care, and find enjoyment in the process — the ultimate goal.

About the Author

Diana J. Lamoreux, RDH, MEd, graduated from Ohio State University in 1972 and practiced dental hygiene for 30 years. She has been a part-time clinical instructor at Cuyahoga Community College since 1981.