Dental hygienists must recognize anxiety and be prepared to offer different techniques to reduce fear over treatment.

by Kathleen Harlan, RDH, and Susan Wancour, RDH

The authors of this article have a combined 38 years of experience as practicing dental hygienists and educators, and have found through experience and discussions with colleagues and dental hygiene students that the main challenge for dental hygienists during patient treatment is managing dental pain. Patient behavior modification is a close second, as is the fear and anxiety that usually coincide with pain.

Almost half of the population of the United States report significant dental fear, and approximately two–thirds report some degree of apprehension when thinking about upcoming dental treatment.1 Therefore, recognition and appropriate management of a patient's pain, fear, and anxiety are very important components of dental hygiene care.

Physiology of Pain

There are several different pain theories, but all focus on the central nervous system as the main message center. The spinal cord is the relay center where pain signals can be blocked, enhanced, or modified before signals reach the brain. Pain perception is a neurological experience — an interpretation and response to the pain message. Factors that can influence a person's pain reaction include physiological, psychological, biochemical, emotional, social, and cultural. Reactions to pain vary from person to person and from day to day.2

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as an "unpleasant sensory and emotional experience arising from actual or potential tissue damage." The pain experience includes the perception of an uncomfortable stimulus and the response to that perception.3 A patient's anticipation leading up to an injection, for example, may lead to hyperventilation or syncope. Pain can be further defined as acute or chronic.

Acute pain begins suddenly and is usually sharp, but may be mild and last just a moment, or it may be severe and last for months. In most cases acute pain does not last longer than six months, and disappears when the underlying cause has been treated or healed. Unrelieved acute pain may lead to chronic pain. A tooth abscess is an example of acute pain.

Chronic pain can persist despite the fact that an injury has healed. Pain signals remain active in the nervous system for weeks, months, or even years. Physical effects include tense muscles, limited mobility, lack of energy, or changes in appetite. Emotional effects include depression, anger, anxiety, and fear of reinjury. Such a fear may hinder a person's ability to return to normal activities. Chronic pain may originate with an initial trauma, injury, or infection, or there may be an ongoing cause of pain. Temporomandibular joint pain that continues well after an injury or surgery is an example of chronic pain. However, some people suffer chronic pain in the absence of any past disease, injury, or evidence of body damage, which is known as psychogenic pain.4

Dental Fear and Anxiety

Dental fear is defined as an unpleasant mental, emotional, or physiologic sensation derived from a specific dental–related stimulus. Dental anxiety is nonspecific unease, apprehension, or negative thoughts about what may happen during a dental appointment. A dental phobia exists when a dental appointment is avoided or endured with intense anxiety. Phobias interfere with normal routines.1

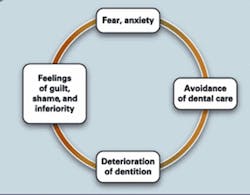

Fear, anxiety, and pain are interrelated — people will endure severe pain before seeking professional care, often because of the fear associated with pain.5 A patient's reluctance to seek needed care is described by Berggren in the Vicious Circle of Dental Anxiety (Fig. 1).6 As pain increases, anxiety increases; as anxiety increases, pain becomes enhanced and therefore less tolerable. Dental fear and anxiety can come from different sources, but are often from a previous bad dental experience, hearing of bad experiences from family or friends, or a general fear of needles. Research has shown that between 50% to 85% of all dental fear happens during childhood or adolescence.1

It is important for dental professionals to understand the implications of fear and anxiety, especially those who have had no personal experience with this phenomenon or who have had little, if any, experience with painful or stressful dental experiences.

A thorough review of a patient's medical/dental history and talking with the patient before treatment may give the professional the insight to reduce or prevent negative psychogenic responses. It is very important to include an open–ended question on the patient medical/dental history that pertains to dental fear and anxiety. This allows the patient to express underlying fears and past negative experiences without feeling threatened, thereby establishing an empathetic, trustful relationship between the patient and hygienist.

The hygienist can also identify patient fear by observing the patient's physical symptoms, such as dilated pupils, elevated blood pressure, heart rate, respiration and blood glucose levels, and decreased salivation. These physical effects are a result of the sympathetic nerve endings producing epinephrine, and are difficult, if not impossible, for the patient to control. Other nonverbal indicators may include "white–knuckling" the arms of the dental chair, and missing or being late for dental appointments. It is important for health care providers to take into account that these are very real and powerful responses to patients and cannot be easily dismissed.

Pain and Anxiety Management Modalities

There are currently many options available to dental professionals to provide patients with pain and anxiety relief. These can be categorized into traditional methods and alternative or holistic methods. Some pain management treatments are more effective when they are combined with other methods. You may need to try various methods with different patients to maintain maximum pain relief.

Traditional methods: Depending upon the severity, symptomatic options may include one or more of the following: over–the–counter or prescription pain medication such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or codeine; antianxiety medications such as diazepam (Valium) or alprazolam (Xanax); topical anesthetics; dentinal desensitizers; fluoride varnish; lidocaine and prilocaine periodontal anesthetic gel (Oraqix™); nitrous oxide/oxygen sedation; nerve blocks with local anesthetic; or in extreme cases, general anesthetic. Of these methods, licensed hygienists can employ topical anesthetics, desensitizers, fluorides, anesthetic gel, and in many states, local anesthesia and nitrous oxide/oxygen sedation.

Alternative and holistic methods: These include techniques that require no specialized training such as music therapy, aromatherapy, behavioral modeling, distraction, deep breathing, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation. The alternative techniques that do require specialized training or education include biofeedback, psychological counseling, systematic desensitization, homeopathy, magnet therapy, crystal therapy, therapeutic touch, meditation, yoga, prayer, hypnosis, acupuncture, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Since the techniques that require specialized training are beyond the scope of dental hygiene education, we will focus on the alternative techniques that hygienists can employ.

Since dental hygienists are naturally empathethic and accommodating of other's needs, it is fairly easy to include some of these stress–reduction techniques for a patient in need. Relaxation therapy can include any variety of techniques designed to trigger the body's relaxation responses (decreased muscle tension, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration).

Most hygienists use relaxation techniques every day, whether consciously or unconsciously, on their patients, their children, and even themselves.

Music therapy is a simple and inexpensive relaxation technique. Research has shown that music can be a significant mood–changer and stress reliever, and suggests that the rhythm may allow for synchronization of the right and left brain hemispheres, which leads to a more relaxed and contented state. Music has also been found to reduce pain during dental procedures.8 Celtic, Native American, and other types that contain drums and flutes are examples of music that lead to relaxation. Patients experience an increase in deep breathing, an acceleration in the the production of serotonin, a lowering of the heart, pulse, and breathing rates, and a slight increase in body temperature. Dental equipment noise, particularly the "drill," can be an audio sensory cue that patients relate to pain. The use of music with headphones helps drown out these noises.

When incorporating music therapy into your office, ask yourself, what type of clientele do we have? What is the age range? What type of music would they like? Does the office play hard rock, soft rock, country, or elevator music? Does the music in the office entertain or distract us, or is it designed with patient relaxation in mind? Take time to choose a variety of music that will suit all tastes. Most discount stores that sell music have an online option to listen to and download music selections at minimal cost. This will enable you to create your own CDs for in–office use, tailored to your patients' wants and needs. It is recommended to have a set of headphones for each operatory.

Another environmental consideration that can be very effective in patient relaxation is aromatherapy, which is the art of using essential plant oils to promote and maintain health and vitality. Essential plant oils are extracted through a chemical process of distillation from aromatic plants, flowers, herbs, woods, and fibers.9 There are approximately 70 essential oils used in aromatherapy, each with its own characteristic odor and therapeutic effect. True essential oils are more than a scented candle or air freshener; if a product claims to have aromatherapy properties, this claim does not necessarily mean that it carries the benefit of true aromatherapy simply because it has a pleasant smell.

Some essential oils have analgesic effects. The pharmacology behind the actions of many essential oils remains undefined and indicates the long and complex path required to full medicinal and pharmacological understanding. It is important to note that in the U.S., aromatherapy is the fastest growing of all complementary therapies in the nursing profession. Though it is recognized as a legitimate part of holistic nursing, aromatherapy is rarely utilized by the medical profession as a whole.10

Current research in aromatherapy is underway, primarily in nursing homes. It has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing agitation, insomnia, and difficult behavior in dementia patients (lavender and lemon balm), and improve the attention span of Alzheimer's patients (sage). In a separate study targeting dental patients, lavender, when vaporized, reduced dental anxiety.11

Behavioral modeling is a common method of behavior modification used by dental professionals who deal with children. The child watches another person undergo a dental procedure, and is encouraged to model the behavior.

Distraction takes the patient's mind off the dental treatment and engages him or her in something else, such as conversation, television, or a poster. This is an effective technique for short–term procedures such as radiographs, taking an impression, or a fluoride treatment.

Deep breathing can help prevent hyperventilation and syncope, which can occur in anxious patients. The hygienist can instruct patients to take slow, deep breaths through the nose and exhale slowly, therefore stimulating the relaxation response.

Guided imagery can be accomplished by the hygienist to help patients take a "mental vacation." Patients should be encouraged to close their eyes to block out negative visual sensory cues, to choose a place where they feel safe and secure, and to concentrate on that place through mental images. Guided imagery tapes and CDs are also available.

The goal of progressive relaxation is to help the patient relax tense muscles. This can be implemented by the hygienist's voice commands or a tape or CD. Along with deep breathing, each muscle group is tensed for approximately 10 seconds, then slowly released, starting from the toes and working slowly up to the forehead. This technique helps distract the patient from the dental procedure.

The dental hygienist must be able to recognize and be empathetic to a patient's pain, fear, and anxiety, and be knowledgeable about the different techniques to help reduce these symptoms. This will lead to greater patient trust and cooperation, as well as more productive and effective dental treatment.

References

1. Darby M, Walsh M. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice, Saunders, 2003, 672–682.

2. Clark M, Brunick A. Nitrous Oxide and Oxygen Sedation, Mosby, 2003, 17.

3. Thomas CL, editor, Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary, Philadelphia, 1997.

4. National Institutes of Health: www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/chronic_pain/chronic_pain.htm, 2007.

5. Malamed SF, Sedation: A Guide to Patient Management, Mosby, 2003.

6. BMC Psychiatry, 2004: 4:10, published online April 19, 2004.

7. Gillman MA, Analgesic Nitrous Oxide Interacts with the Endogenous Opioid System: A Review of the Evidence. Life Sciences 39:1209, 1986.

8. Wanachantarac S, Intawong T, Asasuppakit P, Paramee M, Jintananpom S. Effect of Music for Relaxation on Pain Perception During Scaling, *1204.

9. Perry N, Perry E. Aromatherapy in the Management of Psychiatric Disorders; Clinical and Neuropharmacological Perspectives, CNS Drugs, 2006; 20(4):257–280.

10. Bemis PA. Contemporary Pain Management, http://www.nurisngceu.com/courses/13, 2006.

11. Vignaroli L. Aromatherapy and the Treatment of Pain, http://altmed.creighton.edu/Aromatherapy, updated 7–20–06.

About the Author

Kathleen Harlan, RDH, and Susan Wancour, RDH, are both assistant professors and the clinic coordinators for the Dental Hygiene Program at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, MI. They also teach pain management techniques, including local anesthesia and nitrous oxide/oxygen sedation to their students and to licensed dental hygienists through continuing education courses in Michigan.