I chose to be a dental hygienist 32 years ago and I still love my career. I can honestly say that working with patients is still my passion and gives me great joy and satisfaction. My dedication is felt by my patients. They know and appreciate that I truly care about them.

I am continually learning new things and passing my knowledge on to my patients. Over the years, my role as a hygienist has changed significantly, from being “the girl who cleans the teeth” to that of a true health educator. Now I’m in a position to empower the lives of the people that I treat. Today, dental hygienists have the tools and the opportunity to teach our patients not only how to have a healthy mouth, but how a healthy mouth can help ensure a healthy body as well.

My success as a dental hygienist depends on many skills in order to be a successful educator and to better my patients’ health: communication skills, time management, a caring attitude, and, in my case, the use of a phase contrast microscope. For the past 17 years, I have been using a phase contrast microscope, and I want to help other hygienists understand the incredible impact it has had on my ability to improve the lives and dental health of my patients. This is the story of my success.

Microscopy, motivation, and compliance

Effective communication is a paramount skill for hygienists. Besides a great first impression, effective communication is absolutely essential if you want good patient compliance. The microscope has become my favorite tool to help patients understand what we are treating and to motivate them to care for themselves with very little prodding on my part. It makes my job so much easier. Seeing their own “bugs” makes patients actually want to become healthy and stay healthy … with me as their coach!

Patients are beginning to understand that they can keep their teeth and have a beautiful smile for the rest of their lives. They also read and hear reports in the media about how their dental health can impact their general health. Imagine their reaction when they see their hygienist using a microscope to examine the microbes in their dental plaque, the same microbes they have been reading about that might be causing other health problems. It’s a revelation. Instead of seeing the hygienist as just a tooth cleaner, they see a health-care professional who cares enough to take the time to show them what the problem is - all in a way they can relate to and understand.

Nothing is more gratifying than when a female patient gets out of the chair and hugs me for helping her to realize and really understand what’s going on in her mouth.

I know some hygienists who seem to have problems with patient compliance. Their patients don’t listen to them. Their patients feel lectured to; patients feel they are being told the same things over and over again. I think it is better to teach, not preach. With a microscope, it is easy to teach my patients that periodontal disease is a bacterial infection that can be potentially dangerous to their general health. By becoming well-informed, my patients begin to take ownership of their dental diseases. Motivating them to care daily for their mouths at home is easy when patients understand what they’re doing and why.

Microscopy and time

I graduated from dental hygiene school in 1973 with strong convictions about how to treat people and high hopes for getting them to do what I recommended for their dental health. Imagine my disillusionment when my first position was in an office where the patients were scheduled every 30 minutes. What can you get done in 30 minutes? “Hi, how are you? Open your mouth.” I quickly found out that, if I wanted to make an impact on patients and their health, 30 minutes was not going to cut it. As time went on, I discovered dental practices that realized that the more time you gave to educating your patients, the more success they had with patient compliance and periodontal care as well as their general dental health.

The time factor is vital because education and learning take time. If hygienists are only given enough time to “clean teeth,” they cannot change anyone’s behavior effectively. Microscopy saves enormous amounts of time because one picture is really and truly worth 1,000 words. Once patients see their own microbes, they don’t need long lectures. They want to get rid of those things - now!

Microscopy and teamwork

A team approach is so important. Since the hygienist is not the first or only person patients see in the office, it’s important to educate the entire team, not just the patient. The physical act of scraping debris off of teeth is just a small part of the hygiene visit. All team members have a role in helping patients understand the importance of oral health. From the initial phone call, patients should begin to get a sense of the kind of treatment they will have. When the entire office team is better informed, patients get a consistent message from everyone they meet as to the importance of good dental health.

That’s especially true for new technology like a microscope. Recently, a new assistant started working in our office. On the very first day, she told me she had never been in an office that used a microscope. As she learned more about the organisms she saw on the screen, she asked if I would test her bacteria. Our entire staff has had their own microscopic assays. They are now able to convey their own personal experience to patients. This is how a team works. All members understand what’s going on and are supportive and interested in the health of the patients. This feeling of unity is felt by the patients.

My protocol

I used to have a hard time explaining that bleeding gums were not normal, that pockets over 3 mm were bad. I tried to teach patients that good brushing would “control” periodontal disease. I practically begged patients to floss their teeth and recommended other dental aids for those patients who did not like to floss. Basically, I muddled through, waiting for the bleeding to go away and the pocket depths to shrink, but I didn’t have any scientific proof that anything I did was actually working. I got the feeling that the patients were following my home-care instructions more to please me than to prevent disease. Too many people were having periodontal surgery only to have it done again several years later. They were following recommendations properly but were not staying healthy. There was a lot of frustration for me as well as for the patients.

In 1988, my office got its first microscope, and everything changed for me. I immediately discovered that patients became interested in how to get the bacteria they saw on the monitor out of their mouths.

Over the years, I have developed a protocol that really works with the use of the microscope. This year, my previous dentist retired. I specifically sought out a new office that had a microscope because it was very important to me to continue the same type of patient care I’ve been doing for the past 16 years.

I continue to use the same treatment protocol. On the first visit, I tell the patient: “I’d like to take a sample of the plaque from under your gums to see if you have the harmful bacteria that cause periodontal infections.” Most patients have never heard anything like that before! I tell them that this is how we determine their disease risk and appropriate treatment. There might not be any obvious bone destruction yet, but we can see whether they already have an early microbial infection. Early detection could save them from tooth loss later on. If patients are over 40 years old, diabetic, and have a heart or immune system disorder, identifying harmful oral bacteria might also help to prevent future medical problems. Hardly anyone declines.

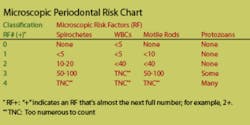

In addition to the microscopic assay, which the patient sees on a video monitor, I take a full series of radiographs. As I full-mouth probe, I explain that pockets 3 mm or less are generally considered within normal limits. When I show patients their bacteria, I first point out the white blood cells (WBC), which are sure signs of inflammation. I then show them any spirochetes, motile rods, amoebae and occasionally trichomonads that might be present. I record the types and quantity on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (too numerous to count). When patients see their own bacteria, they usually say, “Are those things living in my mouth? How can I get rid of them?”

Patients with pocket depths >4mm and a microscopic risk factor (RF) of one or higher will usually warrant a prophylaxis and oral irrigation with an antimicrobial agent. I teach them how to brush and irrigate at home. Patients with pockets >5 mm need a full-mouth debridement, irrigation, HCI, and follow-up appointments for SRP.

At each appointment, progress is monitored with a microscopic assay to determine whether we’re eliminating the infection. My patients are eager to see if the bacteria are going away. Sometimes, the infection persists; but when it does, we know it. In these cases, the immune system may be compromised. Sometimes, the dentist will recommend antibiotics if there are still high bacteria counts even after treatment. We will also recommend vitamin supplementation to boost the immune system including general multivitamins, vitamin C, and CoQ10.

All of my periodontal patients are told from the very beginning that they will be seen on a three- to four-month schedule, which is the best way to monitor their success. Patients also have a microscopic assay on every maintenance visit, something they usually are anxious for me to check. We charge $25 for the assay. Despite most insurance companies not covering the expense, my patients have no problem paying out-of-pocket. The same is true with the charge for oral irrigation because they understand the value of both. I continuously monitor their bacteria each visit. When the assays become negative, I usually extend their microscopic assays to every other visit.

Microscopy and home-care instructions

In the early 1970s when I was in dental hygiene school, home care was all about brushing techniques and interproximal aids. Thirty-three years later, we’re still teaching brushing, but dental floss seems to be the ultimate home-care tool. Yet, despite our best efforts, patients are still struggling with dental floss and still going downhill. Most people hate using dental floss. ”I have to admit that I have not been flossing.” How often have you heard that line?

Why do we keep recommending something people hate? When I see the bacteria in people’s mouths who tell me they floss and use antiseptic mouthwash, I have to question whether dental floss is doing what we thought it should. After many years of microscopic observations and courses, I began to realize that dental floss was not working with periodontal disease. It was not killing the bacteria.

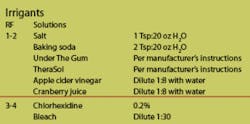

My home-care recommendations include an oral irrigator (Viajet, Waterpik or Hydro Floss) with an antiseptic. Patients with >6 mm pockets use a cannula tip. Antiseptics vary in strength and I have tried quite a few. In most cases, I recommend 0.2 percent chlorhexidine diluted from a 5 percent solution. I also recommend TheraSol and Under the Gum (an herbal product).

For patients at lower bacterial risk, I recommend a diluted baking soda and water mixture in their irrigators. For those patients who won’t use an irrigator, I recommend the Keyes Technique, named after Dr. Paul H. Keyes, formally with the National Institute of Dental Research. That entails using a rubber tip stimulator with a paste of baking soda, peroxide, and water.

I have seen tremendous success with these methods. In my former office with Dr. Barry Buchman, we had patients who had localized pockets up to 10 mm who remained healthy for 10+ years with no tooth loss. Treating periodontal disease as an infection works, but you have to know who is infected and who is not at each stage of care and maintenance. A microscope is essential, not only to detect risk, but to motivate patients to do their home care.

More and more, our profession and the media speak of killing the harmful bacteria that cause “gum disease.” What I question is how do we know who is infected and who isn’t when most of the profession is not testing or identifying the organisms. Patients would be justly suspicious if a physician wanted to treat them for high cholesterol without a blood test. We are certainly under-treating some patients and over-treating others when we treat periodontal disease without microbiological testing.

Despite my many years as a hygienist, I’ve never felt so proud of my profession and my impact on my patients’ health. You know when you are making a real difference in people’s lives when they faithfully keep their appointments, call to make sure they are following your instructions, tell their friends about you and insist that their loved ones get checked to make sure they don’t have a communicable dental infection. All of these things are a testimony to the benefits of using a microscope. The visual impact and scientific credibility of using a microscope has made such a great impression on my patients, I really don’t need to say much more than, “These are your bacteria. We can help you get rid of them and get you healthy, but we need to work together as a team. Together we can do it.” The smile on their faces is all I need. We’ve already won the motivational battle and that is the first step to better health.

Author’s note: This article is dedicated to the people who have inspired me and have worked with me and the microscope. Thank you, Bill Landers, Dr. Barry Buchman, Dr. K. Michael Murphy, Dr. Alexandra Welzel, and Sherri Caplan Feldman, RDH, BS, and team. My success would not be possible without you.