Products relieve oral dryness

by Sheri B. Doniger, DDS

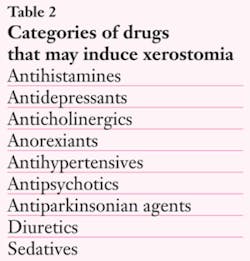

Xerostomia has many etiologies. Although many patients experience xerostomia, it is not a disease state but a symptom. Xerostomia, which is a decreased or absent salivary flow, may be caused by medications (anticholinergics, antiparkinsonians, antihypertensives, anxiolytics, and some antidepressant drugs), head or neck cancer radiation treatment, chemotherapy (antineoplastics) treatments, or Sjögren's syndrome. With the rise of methamphetamine use, we have seen patients exhibit xerostomia with "meth mouth." Smoking also causes dry mouth. Something as ubiquitous as snoring or use of CPAP machines while sleeping may also cause dry mouth in some patients. Xerostomia may also be a symptom experienced by many women who have undergone menopause. Additionally, some elderly patients experience decreased salivary flow with age.

Saliva is generated by three pairs of major and numerous minor salivary glands located within the tissues in the oral cavity, such as the lips, buccal mucosa, dorsal surface of the tongue, and soft palate. The major salivary glands produce 93% of all saliva. The glands are under the control of the autonomic nervous system, along with hormonal influences. Saliva is formed in the acini via an osmotic mechanism. Water comprises 99% of saliva. The remaining components include macromolecules, which are secreted by the ducts into the lumen and formed within the endoplasmic reticulum of the acinar cells.1,2

Daily saliva output is in the range of 500 to 150 mL, although the average daily volume of saliva in the oral cavity is only 1 mL.1,2 Saliva output may be either resting (basal) or stimulated, which increases the flow rate. Mean resting saliva output is 0.4 mL/min., and is highest in the morning. Stimulated saliva output, which is driven by masticatory or gustatory signals, is between 1 to 2 mL/min. When saliva is stimulated, there is an increase in the bicarbonate ions, causing a rise in the pH, and therefore increasing the buffering power against a carbohydrate event.1,2,3,4

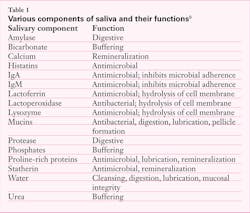

Saliva is an integral component in oral health. Aside from lubricating the tissues, it maintains a neutral-pH environment that promotes tooth remineralization from the wealth of ionic minerals available in solution, and affords an antimicrobial function through immunoglobulins and proteins present in the fluid. Saliva assists in digesting, diluting, and clearing dietary carbohydrates, as well as the buffering of acid exposure after a sugar incident. Due to histatins, proline-rich proteins, cystatins, and statherin, calcium and phosphates are maintained in supersaturation for bioavailability in the remineralization of tooth structure.4 In addition, saliva aids in maintaining mucosal integrity and digestion through salivary enzymes. Saliva is integral to formation of the pellicle, which protects the tooth after eruption (see Table 1).

Saliva's buffering abilities maintain the health of the dentition. For the 20 to 30 minutes after a cariogenic episode, there is a drop in pH. After ingestion of a dietary sugar, the production of saliva ceases once swallowing occurs, and output returns to a resting state within a short time.4,8 The tooth is most susceptible during this time. The need for an increased salivary protective function is highest after a carbohydrate experience.

We truly see the benefits of saliva once it is diminished. Since saliva aids in mechanically removing food debris and bacteria from the oral cavity and teeth, diminished saliva flow will negatively affect the oral tissues. As stated, xerostomia has several etiologies, from simple mouth breathing to drug manifestations, hormonal fluctuations, autoimmune diseases, neurological or psychogenic disorders, and aging. Patients may also exhibit compromised function of the salivary glands through neoplasm, trauma, surgical intervention, or as a sequela of radiation therapy.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8

The main consequence of xerostomia is the dry, burning mouth, which will impact the ability to swallow, taste food, speak, and maintain oral tissue integrity. Demineralization of enamel, an increased caries rate with rapid progression of the lesions, and an overgrowth of Candida will also occur.

Xerostomia may affect up to 20 percent of our senior patient population due to decreased salivary function alone.10 Combine this with the potential for these patients to be taking one or two medications that affect salivary output, and you have a larger issue.11 However, xerostomia is not limited to senior patients. There are over 1,800 medications that cause xerostomia; some may decrease the quality or quantity of saliva flow, and some may have transient effects on saliva (see Table 2). The duration and amount of therapeutic doses may have some impact on each individual.

Aside from medications, certain disease states will cause a decrease in saliva flow. Sjögren's syndrome is an autoimmune process that mainly affects postmenopausal women. It manifests with a triad – the so-called "sicca complex" of symptoms – xerostomia, xerophthalmia, and vaginal dryness. Sarcoidosis and amyloidosis will both affect the secretion of saliva from glands due to granulomas (former) and amyloid (latter) depositing in the gland structure. Several systemic diseases will affect saliva flow, including, but not limited to, diabetes, nutritional and neurological disorders, and dehydration. Cancer therapies, including radiation to the neck and oral cavity, may also affect saliva production. Although some cancer chemotherapeutic medications may cause xerostomia, this symptom is often reversible.

Xerostomia will cause patient discomfort due to the lack of lubrication in the oral cavity, a higher risk of decay due to the lack of a therapeutic flow of ions in the mouth, as well as the potential increase of other flora such as Candida albicans. Patients will experience dryness, the inability to properly digest or swallow food, and an increased caries level. This may be the reason the patient is coming to the office; or we may see manifestations of these symptoms on a routine intraoral inspection.

We have all had patients who have exhibited a loss of salivary flow. Many of them have come to us for solutions to their discomfort. On occasion, the mere adjustment of a personal habit (snoring or smoking, for example) may generate more moisture in the oral cavity. Many products on the market promote with beneficial claims, including glycerin mouth rinses, saliva substitutes, toothpastes, or chewing gums.

One product of note that has come onto the market is XyliMelts by OraHealth. XyliMelts is a time-released, moisturizing, oral adhering disk. Unlike other products, the sustained release is effective over a longer period of time. This small disc adheres to either a molar or the gingival tissue opposite the buccal and delivers 500 mg of time-released xylitol over one to two hours during the day, or up to six hours when used while sleeping. Xylitol has been shown to reduce plaque by inhibiting bacterial growth, decrease caries, and stimulate salivary flow. The effects last longer than the flavor of gum or the dissolution of a hard sugar-free candy. Due to its unique adherence to the oral tissues, XyliMelts are the only xerostomia product that may be used during the night. They are perfect for your xerostomia patients, due to their portability and ease of use.

My patients are highly satisfied with XyliMelts. One male patient, 68, an oral cancer survivor and diabetic who has almost no saliva, was thrilled. He placed discs on the upper and lower, and said that they worked so well he was pleasantly surprised. We had previously tried mouthwashes and different toothpastes. From a man who had such severe saliva depletion, he is now happy with the ability to chew a normal meal.

Another patient, a postmenopausal female, was also very happy with XyliMelts. She said it wasn't "slimy," as she found some of the other saliva replacement products to be, and felt the two layers of the XyliMelts work: one dissolved immediately, and the other over time. She felt the effect was much better than any oral rinse we recommended, and commented on the pleasant flavor.

These were some of the results from two different types of patients who have experienced xerostomia in my practice. They were both excited with the results, which afforded them relief from their condition. With their portability and ease of use, along with the resulting decrease of plaque bacteria, XyliMelts offer a multitude of therapeutic benefits; mainly, the ability to moisturize the oral tissues for a prolonged period of time, even during sleep. XyliMelts are available in either a mild mint or mint-free flavor. They are the over-the-counter treatment of choice for the multitude of our patients who suffer from xerostomia.

Proper diagnosis and consultation with the patient's physician are key to assisting our patients with xerostomia. Using a variety of treatment modalities, we are able to offer them comfort. Depending on the level of salivary damage and saliva depletion, due to whatever source, other options may be necessary for complete care. The product we used was helpful in achieving a level of comfort for eating and sleeping for the select patients in our office.

For more information on XyliMelts, please visit www.orahealth.com.

Sheri B. Doniger, DDS, has been in the private practice of family and preventive dentistry for more than 20 years. A dental hygiene graduate of Loyola University prior to receiving her dental degree, her current passion is focusing on women's health and well-being issues. She may be contacted at (847) 677-1101 or donigerdental@aol.com.

References

1. Mandel ID, Sreebny LM, Izutsu KT, Fox PC, Ferguson MM. A symposium on the endogenous benefits of saliva in oral health. March 21, 1989. Compend Suppl. 1989;(13):S448-88.

2 Diaz-Arnold AM, Marek CA. The impact of saliva on patient care: a literature review. J Prosthet Dent. 2002 Sep;88(3):337-43.

3 Dowd FJ. Saliva and dental caries. Dent Clin North Am. 1999 Oct;43(4):579-97.

4 Edgar WM. A role for sugar-free gum in oral health. J Clin Dent. 1999;10(2):89-93.

5 Edgar WM, O'Mullane D. Saliva and dental health. Clinical implications of saliva: report of a consensus meeting. British Dent J. 1990;169:96-8.

6 Edgar WM. The clinical implications of salivary stimulation. General Dental Practitioner. 1989;Jul/Aug: 9, 10, 12.

7 Navazesh M, Denny P, Sobel S. Saliva: a fountain of opportunity. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2002 Oct;30(10):783-8.

8 Lenander-Lumikari M, Loimaranta V. Saliva and dental caries. Adv Dent Res. 2000 Dec;14:40-7.

9. Doniger SB. Saliva, chewing gum, and oral health. Dent Today. 2004 Sep;23(9):136, 138, 140-1; quiz 141.

10. Xerostomia. The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec08/ch094/ch094f.html. Updated March 2009. Accessed March 15, 2010.

11. Dry Mouth. Oral & Dental Health Basics. Colgate World of Care Web site. http://www.colgate.com/app/Colgate/US/OC/Information/OralHealthBasics/CommonConcerns/DryMouth/DryMouthMayo.cvsp. Published April 6, 2007. Accessed March 15, 2010.

Past RDH Issues