by Terry Carnes, RDH

While casually reading the pages of RDH, I stumbled upon an ad in the classified section for a company called Aramco, which is based out of Houston and doing business in Saudi Arabia. It’s the company that actually discovered oil in Saudi Arabia in the 1930s. The company was looking for a hygienist to help with the dental needs of the employees in Saudi.

I sent my resume to Houston and waited.

Hofuf Caves and Camel Market

About a month later, I received a phone call from the human resources office informing me that the two hygiene positions had been filled, but they would keep my resume on file. A couple of weeks later, I received another call asking me if I was still interested in the position. My answer was affirmative, so a telephone interview was arranged with a periodontist and general dentist working for the company in Saudi. The interview was short and to the point, such as what was my approach to perio patient therapy, and was I familiar with ultrasonics.

I was told that as a woman, I wouldn’t be able to drive a vehicle off the company compound but would be able to drive on the compound. The female Saudi periodontist explained that life for women in the Kingdom was rapidly changing and improving. But my main concern was the issue of security, so I asked them about that. They explained that the Saudi National Guard has the outer perimeter of the compounds under its control, and that Aramco hires its own security for the gates leading into the compounds. This put my mind at ease.

Apartment in Udhailiyah, Saudi Arabia

I soon learned I was a successful candidate for the position and the next step was a background check, which I cleared. I was then sent a plane ticket to Houston for a physical and orientation, which I attended with about 20 other people, most of whom were couples going over to Saudi Arabia for the first time, and two male engineers who had been previously employed by the company. I was the only single female in the room. I completed my visa application paperwork (religious affiliation was required since neither atheists nor Jewish people are allowed in the Kingdom), and returned to Portland to await my final employment proposal.

A couple of weeks later, a FedEx package arrived with my official employment proposal, which included the details on the moving company that was transferring personal items to my condo in Saudi. Every single item had to be labeled with my name and employee number, since all shipments that arrive in Saudi are dumped together into large bins and examined with a fine tooth comb. The only way I could hope to receive my personal effects was to label them.

The entire trip over took about 18 hours via Seattle to Amsterdam to Dammam, Saudi Arabia. After I cleared Saudi customs, a taxi driver escorted me to the Aramco office in the airport where a company representative completed my paperwork, then the driver directed me and two other new female employees to his van. He drove us the 30 minutes or so to the main compound in Dhahran, where we were given a room in the hotel on the compound. Since I was new, I was relegated to a clinic on the medical compound of Al Hasa, located in the desert approximately two hours south of the main compound.

The next day, the director of the Al Hasa clinic, Dr. Jack Moyer, picked me up and drove me to the compound where I would live, which was a one-hour bus ride away from Al Hasa. I lived in an apartment in a barracks-style building until my permanent accommodations were arranged a couple of months later. The compound was very pleasant with a bowling alley, movie theater, dining hall, cafe, swimming pool, and tennis courts. On the compounds, Western women did not have to wear the “abaya” robe or cover their heads. The Saudi women who lived on the compounds did so out of cultural habit. However, conservative clothing was encouraged and only one-piece bathing suits were allowed at the pool.

At 6 a.m. Saturday through Wednesday, the company bus took us to the clinic where we worked from 7 a.m. until 3:15 p.m. with a half-hour for lunch. The return bus left at 3:30 p.m. sharp. The clinic was very modern and clean with impeccable infection-control procedures, some better than what I see in the States. Each hygienist had her own office and computer with a shared assistant. Our patients were the company’s Saudi employees and their dependents. While most male employees could speak English, most of the wives and dependents could not, so learning some Arabic was very useful. A native Arab-speaking dental assistant who provides valuable one-on-one information for one-hour intervals worked with us most days.

The author’s nephew, Serj, tries on Saudi Arabian garb.

Most of the dentists in the clinic were either male or female Americans or males from other Arab-speaking countries. There were several Saudi dentists and male hygienists, while the rest of the hygienists were American women. The entire support staff and assistants were from the Philippine Islands, and the reception staff consisted of local Saudi men.

The hygienists used ultrasonics on most patients and the calculus was very tenacious, with middle-aged patients presenting as the most difficult. There was a very good orthodontic program, with three- to four-month intervals for prophies and oral hygiene instruction. The water on the company compounds is fluoridated, while the water in the town is not.

The clinic had a separate waiting room for the women, with a door and a curtain behind it so a woman still could not be seen from the hallway when the door opened. Only female providers or assistants were allowed in this room to call patients. All of the operatories had doors so the women could unveil their faces for treatment. Often a woman would have a male relative with her while I was working.

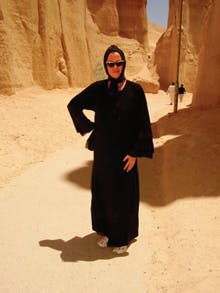

Life for single women in Saudi Arabia can be very challenging. Off the compounds we are not allowed to travel with men who are not related to us. The company has buses or official taxis that run between the compounds and the Saudi towns. Some of the cultural rules are somewhat relaxed for Western women. In the less conservative cities such as Dhahran, Western women don’t have to cover their heads but still must wear the abaya. In Al Hasa, close to where I worked, a scarf as well as the abaya had to be worn.

No alcohol or pork is allowed into the Kingdom, and anyone caught trying to smuggle in these items is deported. Most Westerners and quite a few Saudis head to the small island of Bahrain, which is connected to Saudi Arabia by a causeway that takes about 45 minutes to cross, for a little rest and relaxation. Women are free to dress as they want there, and alcohol and pork are available.

I was lucky enough to be invited to a Saudi wedding, and it was quite the experience! The men and women are segregated into separate buildings for the reception (guests don’t witness the religious ceremony), and the women wear garish evening gowns and heavy makeup. Western guests are encouraged to eat first from platters of rice, lamb, chicken, and fruit set upon cloths spread on the floor. Female musicians accompany CDs for the guests’ dancing pleasure.

Although Aramco began as an American company, the Saudis have had control since the late 1980s. They have company policies that would be considered illegal in the United States, such as married men are allowed to bring their families with them to reside, but married women must hire as “bachelor” status and their husbands are allowed six-month visitor visas only. If employees decide to marry while employed, the woman must take “casual” status, which means she will do the same work for the same hours with a cut in pay. The man’s salary remains the same.

Female hygienists considering working in Saudi Arabia must take into consideration the constraints on personal freedom. Although politically the country appears calm and stable, there are isolated incidents of terrorism. One occurred last year at the Aramco facility in Abqaiq - the first terrorist attack in the company’s history.

Those thinking of going should consider the volatility of the entire region, which could be outweighed by the excellent pay and benefits, as well as the chance for professional development. A good course in basic Arabic would be helpful since a new hire’s chances of being assigned to the main clinic are not good. English is spoken in the other clinics, but perhaps not by the dependents being treated. Finally, a keen sense of adventure is a must for employment in Saudi Arabia!

Terry Carnes, RDH, graduated from the Indiana University School of Dentistry in 1994, and obtained a bachelor’s degree from the Oregon Institute of Technology in 2005. She began her career in Bloomington, Ind., and Indianapolis. She has also worked in Stuttgart, Germany, for a private dental practice. She claims to be the first American hygienist to take the Irish hygiene board in 1997 at Cork, Ireland. For the past eight years, her home base has been in Portland, Ore.