Whether the patient is a wayward mountain lion or a theme park`s killer whale, veterinary dentistry offers hygienists a unique peek at the animal kingdom.

Carol Weldin, RDH

Veterinary dentistry is the fastest growing specialty of veterinary medicine. Out of the 60,000 licensed veterinarians in the United States, approximately 75 percent perform routine dental prophylaxis procedures and 5 percent perform more in-depth procedures on companion animals such as endodontics (see related article), prosthodontics, orthodontics, and oral surgery.

While many veterinarians have been performing prophylaxis for years, a few factors have played a key role in its rapidly growing popularity. In 1988, the American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) was formed under the auspices of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). The AVDC is the certifying body for the board-certified specialty of veterinary dentistry. The college currently has approximately 40 diplomates in the United States.

Four pathways may lead a veterinarian to diplomate status in the AVDC:

- Conforming residency (which is a full-time program conducted at an institution or practice).

- Non-conforming residency (which is a specific program submitted for approval; it may be full-time or part-time and may be conducted at several institutions or practices).

- Alternate pathway program (which is designed as a customized part-time program conducted in private practice under the guidance of an AVDC diplomate).

- A fourth pathway is structured for individuals who are graduates of both dental and veterinary schools.

The Academy of Veterinary Dentistry, formed by a group of individual veterinarians whose goal was to recognize dental education, was established in 1986 and held the first formal veterinary dentistry meeting in 1987. This accrediting body is primarily responsible for continuing education. All AVD and AVDC members must be licensed DVMs (Doctors of Veterinary Medicine).

A third association, the American Society of Veterinary Technicians, is much larger (around 800 members), since it addresses the professional concerns of animal health technicians (AHTs). AHTs are part of the veterinary team and usually perform routine prophylaxis procedures along with their other responsibilities. The ASVDT, which was organized in 1994, is in the process of developing protocol for the society. The first formal educational program was hosted in September 1995 at the World Veterinary Dental Congress/Veterinary Dentistry Forum in Vancouver, B.C.

A lion`s walk for relief

Many of the veterinary schools today place an academic emphasis on dentistry. Since 1992, the University of California at Davis has had a state-of-the-art dental operatory. I have been affiliated with UC Davis since 1993. It was very exciting to assist in root canal procedures on a non-domesticated mountain lion that had been captured by Fish & Game Department officials. When caught, the mountain lion was walking down the street of a new residential subdivision in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains in Northern California.

In addition, UC Davis veterinarians recently performed root canal treatment on a miniature horse. The case load varies since there is a large referral base at this institution.

Washington State University is in the process of developing dental curricula for its veterinary students. Other veterinary schools with dental emphasis are the University of Illinois and Auburn University. The University of Pennsylvania veterinary medical teaching hospital has a full-time staff hygienist - Bonnie Miller, RDH.

The other factor that has played a key role in the advancement of veterinary dentistry is client awareness. Veterinary pharmaceutical and nutrition companies have been instrumental in underwriting the development of pamphlets and brochures which educate clients about the importance of routine prophylaxis procedure. The procedure, of course, aids in the prevention of periodontal disease, which affects 75 percent of animals who are over three years old.

As with the human population, companion animals are living longer. This results from nutrition research and dietary changes for animals, as well as an emphasis on geriatric medicine in the veterinary schools.

Veterinarians and technicians have been very diligent in instructing clients on the importance of home care. Many animal clinics are now dispensing toothbrushes with special dentifrices and offer chlorhexidine solutions to clients.

An unique way to practice

The RDH can play a role in this alternate practice setting. As the periodontal therapist, they can act synergistically with the veterinary profession.

While a liaison between the American Dental Hygienists Association and veterinary dentistry, I observed a certain amount of interest in this career option. Several RDHs have asked me about the feasibility of establishing themselves in various settings. There is, however, a certain limitation to the scope of duties a RDH can perform due to induction, administration, and monitoring of general anesthesia. According to veterinary practice acts (which do vary by state), unregistered assistants (RDHs fall into this category) may perform oral prophylaxis procedures under the direct supervision of a DVM or a licensed AHT.

A routine prophylaxis procedure on a companion animal usually consists of a complete blood count (CBC) to determine any contraindications for treatment. An initial assessment (depending on the animal`s willingness to cooperate) can be conducted at even a routine vaccination appointment by pressing a Q-tip against the tissues to detect edema and bleeding.

But use of a perio probe for a more comprehensive exam and accurate diagnosis of the disease process will, in all probability, occur when the animal is under general anesthesia.

Not quite the same teeth

Many of the same instruments used in diagnosis are adapted for veterinary dentistry. The Williams type probe, due to 1 mm degree markings is more preferable for felines, since the range of pocket readings may only be 0-1 mm. With canines, the Marquis type probe may also be used. Unless severe periodontitis is present, the pocket depth range may be 0-3 mm.

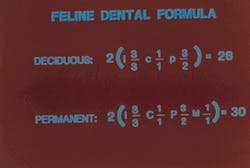

The canine and feline dentition differ in nomenclature, as well as the number of permanent teeth. Canines usually have 42 permanent teeth to felines 30. Note, they both have six incisors!

Two methods of charting are accepted by the AVDC and AVD - anatomic and Triadan. With the former, the tooth type is indicated by an I (incisor), C (canine), P (premolar), or M (molar). The number of the tooth is indicated by a superscript for the maxillary arch and a subscript for the mandibular arch. Superscript or subscripts are placed on either the right or left side of the initial, depending on side of mouth. For example, the maxillary right incisor is I1.

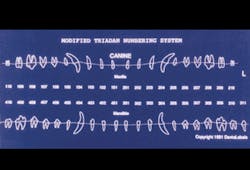

The Triadan system assigns a three-digit number to each tooth. No "letters" are used. The first number represents the particular quadrant - upper right (1), upper left (2), lower left (3), and lower right (4). The next two digits designate tooth types, starting at midline with 01 being the first tooth from centerline and moving distally around the arch. For example, the maxillary right first incisor is 101. Exceptions to this formula occur with feline dentition. Since there are reduced numbers of teeth, gaps are left in the numbering sequence for the missing teeth; this is referred to as the modified Triadan system, developed by Michael Floyd, DVM, in 1991.

Prophylaxis procedures are similar to the ones performed on our human patients. There are some differences, however. Much research has been conducted regarding bacteremia and the use of pre-op medications. The recommended procedure is to administer an antibiotic such as Antirobe (clindamycin hydrochloride).

Certain breeds may require more prophylaxis treatment, such as toy poodles who have a higher incidence of dental disease and Dobermans who are very prone to heart disease. Post-op meds may also be administered. Since the animals are anesthetized, ketamine, I.V. valium, and gas anesthesia such as Halothane or Isofluorane (more rapidly metabolized in the system) will often be used.

Instrumentation is also similar to what we use for our patients. As the knowledge base increases for veterinary dentistry, so does the instrument selection. Ironically, ultrasonics have been used for years. So the transition to periodontal debridement has been well accepted. Other gross calculus removal instruments such as roto pro burs and tartar forceps are not as recommended as they have been in the past.

Hand scaling with universal curettes and scalers is common. The challenge comes when the animal is placed in lateral recumbancy (on its side) with an endotracheal tube inserted. Aspiration can be critical, and the hygienist/technician must be constantly aware of this.

Polishing procedures with prophy pastes formulated for veterinary use are also used. The final procedure of oral irrigation is usually a CHX gel (chlorhexidene) in 0.12 percent concentration. Certain agents widely used in human dentistry are contraindicated since phenolic compounds in the formulation are toxic to felines.

Home care for the pet

When treatment is completed, the client must be educated about the importance of the procedure performed and, more importantly, follow-up home care. This is also when the recommended aids are dispensed. The more diligent of clients may even be able to perform brushing with a rotary instrument. Proper diet and newly developed products such as tartar-inhibiting supplements to dry dog food all play an important role in maintenance of oral care.

The field of veterinary dentistry truly offers a rewarding and exciting experience for those who choose to involve themselves.

One colleague, Marsha Venner, RDH, AHT, who practices in a large specialty practice in Houston, Texas, said to me on several occasions, "It really was the right thing to do, complete the course for animal health technicians, which enables me to not only perform anesthesia procedures but have the best knowledge base I possibly can as an RDH!"

At times too, it can be fun when the "stars" are brought in for treatment. David Nielsen, DVM, who has practiced in Manhattan Beach, Calif., has an "autographed" picture on his desk of the Jack Russell terrier from the popular television series, Frazier. Dr. Nielsen performed a root canal and crowned this famous K-9`s tooth.

Another formidable story is the abscessed tooth extracted from a killer whale who performs at Marine World Africa USA in Vallejo, Calif. The zoological medicine team from UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital made a "house call" to perform the necessary procedures.

References available upon request from the author.

Carol Weldin, RDH, has been involved in veterinary dentistry since 1981. A long-time associate of Dr. Ron Gammon, a diplomate to the American Veterinary Dental College, Weldin represents several dental manufacturers to the veterinary profession and is co-editor of 1991`s Veterinary Dental Techniques (published by Holmstrom, Frost & Gammon).

Dental operatory at the University of California at Davis caters to veterinary patients.

Feline chart accounts for fewer teeth in cats.

Modified Triadan numbering system for canines.