At the end of a long day - from left: Mary Beth Dey, RDH, Leah McMasters (a missionary intern and Bible school graduate), and Marilyn Morgan (a kids' missionary).

At first glance, Mary Beth Dey appears to be a regular, hard-working dental hygienist. Nothing unusual there. She's a 37-year-old single mom raising a teenaged daughter who will soon be learning how to drive. Many parents face that specter as well. On wintry Sunday afternoons, she likes to go cross-country skiing near her home in Ohio. Again, many people do that. Is there anything particularly unusual about Mary Beth Dey, RDH? Try this: Every spring and fall, Mary Beth becomes a dental hygienist with a mission - to the garbage dumps of Mexico City. To finance the privilege of working in the dumps on her "vacations," Mary Beth works six days per week at three different dental offices. As such, the time she takes for this purpose is uncompensated. Her rewards are not monetary, but they're the best kind - the deep satisfaction of helping some desperately poor people live just a little bit better.

Whole communities live in the dumps called Nezas, a painfully understated name meaning "small, poor communities." While these places certainly look makeshift, incredibly, they are sustained communities with generational histories. Couples get married there, babies are born there, children grow up and raise their own families there, and the elderly die there. The residents live under tents and tarps and whatever else they can use from the trash and garbage deposited daily. That which they can't eat, use, or wear gets fixed up and resold or traded in the streets of nearby towns and villages. Each Neza has a "mayor" of sorts, called the Lord of the Dump. He is the person who negotiates all dealings with outsiders for the community.

Dey's trips to Mexico began seven years ago when she was doing mission work with her home church. At the time, she was performing children's gospel puppet shows in the streets of Mexico City. While in the hotel elevator after a hot afternoon of puppeteering, Mary Beth met an English-speaking stranger who struck up a conversation with her. The lady was the regional operations director for Operation Serve Inter national, a nonprofit, Christian-based service ministry. When the director learned that Dey was a dental hygienist from the States, she explained her organization's urgent need for Dey's professional services at the dumps. The director asked Mary Beth to accompany the mission team on the following day.

Mary Beth was somewhat taken aback by the request, but agreed to go to work with the Operation Serve team for one day at the Santa Catarina dump, about an hour's drive outside Mexico City. The team hired an old Greyhound-type bus and its owner/driver to haul them to the dump with all their equipment and supplies, including a big cooler of purified water and safe foods to drink and eat every day of the week for the duration of the mission's work there. For the residents, the team also brought food, drinks, and games for the children.

Accompanying Dey was an American physician, an English nurse, an optician, a beautician, a Mexican husband-and-wife dentist team, as well as several interpreters. She had heard about children wearing rags and subsisting on garbage, but it still seemed incredible. As their bus was pulling into the dump, her own eyes decisively convinced her of the appalling reality of what she'd heard. She saw adults and children picking through mounds of garbage barefooted. She saw scattered tarps set up all over the dump - the dwellings of an entire community actually living in garbage amid swarms of flies. Mary Beth worried a little about what she had gotten herself into that day, but when she saw all the ragged and soiled children running up to her bus excitedly waving and cheering, she knew she had made the right decision. She knew her skills would be used in the best way possible right there.

Stepping off the bus, Dey was struck by the fetid odors wafting about her. She hoped and prayed that she would soon get accustomed either to the odors or her nausea; otherwise, she doubted if she'd be able to endure, regardless of her strong desire to do so. Thankfully, as she began meeting the children and unloading the cargo, her nose gradually got used to the stench. The flies were another story. They were going to be persistently bothersome all day long.

It was to be a long and emotional day. She had never seen such extreme need, not only for her professional services, but also for loving attention and tenderness. The adults as well as the children loved just being touched in a kind and caring way. They seemed to soak it up, and it was just as healing as anything else she had done for them that day. Mary Beth could see how much it meant to them, and she sensed her own feelings of genuine affection for each one. After this first visit, realizing how many people she had helped, how appreciative they were, and how wonderfully tired she felt, she decided to join the Operation Serve team on a regular basis.

On their visits to the Nezas, the team sets up and tears down its respective workspaces and equipment on a daily basis. Un fortu nate ly, they cannot leave their supplies and equipment on site. The team has learned the hard way that the temptation to resell them is often too strong to resist. It is simply a fact of life there. Taking this into account, the setup and teardown procedures take an hour each, including unloading and reloading everything on the bus. Upon arrival, as soon as the bus bounces to a halt, a designated window is opened and a worker helps the residents choose from among four picture cards that illustrate their need for dentistry, eye and vision care, medical care, or a beautician's services. The need for a beautician in a dump may seem odd, but in a place where there are no bathrooms, showers, shampoo, or even much soap, the beautician's services are greatly appreciated and contribute to the residents' health and well-being. With picture cards in hand, the residents are sent to the proper areas, and the cards confirm that they're in the right place.

The two dentists and Mary Beth start by erecting tarps of their own to provide some shade. Then they begin setting out boxes of instruments and sup plies for the day's work. Equipment is Spartan, consisting of chaise lounge lawn chairs for the patients, hand scalers, various forceps and elevators, and a couple of donated air and water syringes powered by a portable compressor and a lone, cold faucet near the dump's utility shed. The boxes are opened and a supply table is set up and stocked with toothbrushes, masks, gloves, instrument packs, medicaments, anesthetics, patient napkins, cotton rolls, and gauze in various plastic tubs. Dey notes that paper goods always are in short supply, as well as masks, gloves, and anesthetics. The mission team makes the best use of everything, and nothing goes to waste.

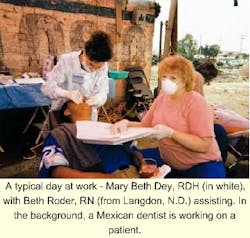

A typical day at work - Mary Beth Dey, RDH (in white), with Beth Roder, RN (from Langdon, N.D.) assisting. In the background, a Mexican dentist is working on a patient.

Operative work most often consists of extractions and treatment of infections. The list of "usual" dental items and instruments that Dey routinely works without is extensive. There is no operatory, no proper chair or tray table, no lights except for the sun, no prophy angles, no ultrasonic unit, no sterilization room, and no vacuum system. Patients expectorate into a plastic cup they hold in their hand. When the cup is full, Dey wraps it up in her latex glove for disposal and gives them a fresh cup. Of course there is no sewer system or biohazard or sharps-disposal facilities, but there is a section of the dump reserved for such waste.

Dey works only with well-worn hand scalers and curettes for long hours. She keeps them sharp, but they're wearing thin.

"An ultrasonic unit would be a godsend," she says, "but it hasn't been donated yet. My hand gets pretty tired."

Tired indeed. Mary Beth has a gift for understatement. These patients are the toughest to be found anywhere, and she cleans their teeth one after the other, all by hand. Electricity is available, and it's possible to get water to an ultrasonic unit if she had one to use. She also suggested that a few self-contained portable dental units like the military uses would be ideal for work in that environment.

In the Nezas, tooth decay, very heavy tartar, and periodontal disease is rampant and affects all ages. Dey encountered a five-year-old boy who had an edentulous maxilla, with his mandibular teeth not too far from the same fate. Candy and soda pop are staple foods for these children and comprise most of their few daily pleasures. Money earned from selling recycled trash is used to buy food, but its nutritional value is typically low and deficient in complete proteins and vitamins. Consequently, many ailments stem from poor nutrition and low immune system response. The "elderly" residents are in their 40s and 50s, but appear much older. Lifespans are typically short.

Instrument care consists of a detergent soak and scrub, rinse, and disinfection in a tub of cold sterile solution, which loses its effectiveness above 80

Remember the swarms of flies? The high altitude makes the climate quite dry, so the flies aggressively seek moisture wherever they may find it - including, but not limited to, a person's eyes and mouth. The Neza residents have more or less accepted the ubiquitous pests, but the care team still expends much energy swatting at flies - not only the ones pestering them, but also those lighting on and in their patients' eyes, noses, ears, open mouths, and wounds. Then there are the fly larvae - well, you get the idea without getting too graphic. On many fronts, life is hazardous and extremely unpleasant in the dumps.

I asked Mary Beth how these experiences have changed her. She ex plained that she has a far greater appreciation for living in the United States, and that she has problems with spoiled Americans who complain about little things that don't matter.

"Most Americans just don't realize how good they have it in the U.S.," she said, "and, in many ways, our country's poor people live better than the average Mexican."

While not necessarily "politically correct" to mention, her statement is based on direct observations and well-documented facts. Being fully acquainted with the conditions there, I asked if she still looked forward to returning to the Nezas.

She replied, "I never mind going, but I always love coming home, and it always feels good to get back to my own culture."

Mary Beth said the trips help her to be fiscally responsible and disciplined. She explained that the extra hours she works have a clearly defined purpose, which compels her to live within her means in order to save enough money to finance the mission trips.

Mary Beth said the rewards of helping in the Nezas are deeply satisfying, and also fulfilling for her hygiene career. She values making new friends, especially among members of the mission team, who come from different parts of the world to help. She explained that the adversities they face together and their unity of purpose strengthen their sense of friendship and camaraderie. Dey and her team members know they're able to make the best use of their skills by helping these extremely needy people. Is this some sort of well-kept secret? As soul-satisfying as these trips are for all involved, perhaps they really are vacations after all.

Tax-deductible supplies and equipment contributions may be sent to:

- Operation Serve, c/o Store-More, Unit 63, 2305 N. McColl, McAllen, TX 78501

- E-mail: [email protected]

- Web site: http://www.operationserve.org

Ted Anibal is a free-lance writer with clinical experience in all dental specialties, including hygiene, crown and bridge, and office administration. He also has extensive knowledge of dental materials, equipment, and office design. Married 25 years to a hygienist, Anibal currently resides in Tulsa, Okla.