Is the hygience operatory a...PROFIT CENTER......or just a convenience for the patients

by Annmarie E. S. Bernardi, RDH, BS, and Richard A. Bernardi, PhD, CPA

Have you ever increased your production, been ready to ask for a salary increase, then learned that the break-even point for hygiene has increased? A comment many hygienists hear from their dentist is, "The hygiene department is just a convenience for patients. It really does not make any money, and it runs at a loss or break-even at best." If the hygienists do not understand cost allocation, how can they challenge this misinformation? Hygienists should ask, "How much of the rent and support staff salaries were allocated to hygiene, and how did you arrive at these allocations?" Our analysis provides hygienists with a framework for viewing their contribution to profitability.

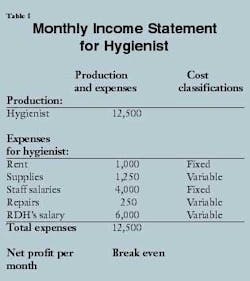

Our example uses a practice that grosses $50,000 per month — $37,500 for the dentist (75 percent of total production) and $12,500 for the hygienist (the remaining 25 percent of total production). While the dentist's production is three times the hygienist's production, they both care for the same number of patients each day. In this example, the practice has monthly fixed costs (those that do not vary because a hygienist is on staff) of $3,000 for rent and $8,000 for the salaries of the dental assistant, insurance coordinator, appointment scheduler, and receptionist ($100 per day x 20 days x 4 people). The practice's variable costs (those that vary because a hygienist is on staff) for the month include $2,500 for supplies, $500 for equipment repairs, and $6,000 for the hygienist's salary ($300 per day x 20 days).

Initially, we allocate half of the supplies, staff salaries, and repairs to hygiene because half of the patients are seen by the hygienist. Additionally, we allocate a third of the rent to hygiene because it uses one of the three operatories. The allocations to hygiene and the classifications of these costs are shown in Table 1. Given these initial allocations, the data indicate that hygiene is only breaking even because its $12,500 in production is exactly equal to its $12,500 in expenses.

Hygiene's contribution to profitability

Our study covers material that hygienists should understand when confronted with the statement, "Hygiene is just a convenience for the patients — it really does not make any money." When evaluating the overall profitability of the practice, the dentist must decide to continue or drop dental hygiene. The decision to discontinue an unprofitable portion of the practice seems obvious. However, redistributing costs that do not change with the level of production may make this the wrong decision.

The dentist must determine the costs that arise from offering hygiene. A critical question in the analysis is, "Would any of the expenses change if hygiene was discontinued?" Or, "Which costs increase with hygiene in the practice?"

Our initial example allocates 50 percent of the support staff's salaries to hygiene even though hygiene provides only 25 percent of the practice's production. While some would argue that you might allocate these costs differently, others would maintain that the difference in the bottom line would not be significant. Since expenses such as rent and support staff salaries would not change if hygiene were discontinued, allocating part of these costs to hygiene allows the dentist to be more profitable with a hygienist than without one. We use this example to create two income statements — one with the hygienist and one without (Table 2).

It initially appears that discontinuing hygiene would not affect profitability because hygiene is covering its costs (breaking even from Table 1). However, because some of the costs are fixed (they do not vary when hygiene is added or discontinued), this is not the case (Table 2). Hygiene is only breaking even because of the allocation of fixed costs such as rent and support staff salaries.

Our Table 2 data show that discontinuing hygiene would be the wrong decision. While costs decreased by $7,500 ($6,000 for the hygienist's salary, $1,250 for hygiene supplies, and $250 for repairs) the "without hygiene" alternative decreases production by $12,500.

Even though we used the same data in both scenarios, the outcome is quite different as evidenced from the two income statements. What we initially overlooked was the $5,000 contribution ($12,500 in production less $7,500 in variable costs) hygiene makes to a practice's profitability each month.

Consequently, the notion that "hygiene is just a convenience for patients" is misleading. Clearly, hygiene increases the practice's profitability.

If the dentist decides to reduce the support staff when hygiene is discontinued by assigning the appointment scheduler's duties to the receptionist (a normal combination in small practices), profit would still be lower. If all of the support staff's salaries were equal, the reduction in the expenses for the "no hygienist" scenario would be only $2,000 ($8,000 divided by four support staff members). If both hygiene and the scheduler's positions were eliminated, costs would decrease by $9,500 ($6,000 for the hygienist, $2,000 for the appointment scheduler, $1,250 for hygiene supplies, and $250 for hygiene repairs). However, production is still $12,500 lower. Consequently, while the monthly profit increases to $27,000 ($25,000 plus the appointment scheduler's salary of $2,000), it is still below the $30,000 level in the "with hygienist" scenario (Table 2).

Allocating costs

In cost allocation, one should always try to determine what causes the costs to occur. For example, salary increases or decreases are usually caused by the number of hours worked. Although we correctly used the amount of operatory space to allocate rent, we incorrectly allocated the support staff's salaries and supplies by using patient load to apportion these costs. We will assume that the dental assistant, insurance coordinator, appointment scheduler, and receptionist all earn the same monthly salary of $2,000 ($8,000/4). While the dental assistant may help the hygienist in periodontal charting, this task is not required for most appointments. When charting is required, it is a small part of the appointment. Consequently, we believe only 5 percent of the assistant's salary should be allocated to hygiene.

One could argue that the more complex the procedure, the more paperwork needs to be filed for insurance purposes. Since the dentist's production is $37,500 (or 75 percent of total production) and the hygienist's production is $12,500 (or 25 percent of total production), we believe that only 25 percent of the insurance coordinator's salary should be charged to hygiene. Finally, we agree with allocating half of the receptionist's and appointment scheduler's salaries to hygiene because one half of the patients belong to hygiene. These reallocations now charge the hygienist with:

• $100 ($2,000 x 5 percent) of the dental assistant's salary

• $500 ($2,000 x 25 percent) of the insurance coordinator's salary

• $1,000 ($2,000 x 50 percent) of the appointment scheduler's salary

• $1,000 ($2,000 x 50 percent) of the receptionist's salary

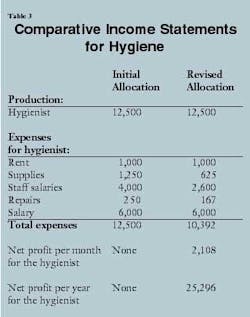

This allocation results in charging the hygienist with $2,600 of the support staff's salaries. Similarly, we believe production should be used to allocate supplies at $625 (25 percent of the $2,500 cost of supplies).

The monthly repairs were divided equally because the hygienist serves the same number of patients as the dentist. However, the dentist has two operatories. If we allocate repairs on the equipment used, the dentist should be charged two thirds of the cost, or $333, and the hygienist $167. One might suggest charging repairs to the equipment's user. Since hygiene usually inherits the oldest equipment, this would unfairly shift the majority of maintenance costs to the hygienist.

While our initial example shows the hygienist breaking even, further analysis suggests that the monthly "over" allocations to hygiene amounted to:

• $1,400 in support-staff salaries

• $625 in supplies

• $83 in maintenance costs

Rather than breaking even, hygiene generates a monthly profit of $2,108 (Table 3) or an annual profit of $25,296. In addition to providing a monthly profit of $2,108, the hygienist contributes $3,600 towards the fixed costs of rent ($1,000) and support staff's salaries ($2,600), which still have to be paid with or without the hygienist.

Consequently, the statement, "The difference in the bottom line will not be tremendously different" if the costs were allocated differently, is incorrect. While patient load may provide an easy way to estimate cost allocations, it can be challenged and the differences are significant. Finally, if staff salaries were not equal, the dental assistant and insurance coordinator would probably be paid more. If this is true, the allocation to the hygienist is lower because the allocation rates for the receptionist and scheduler are 50 percent compared to the lower rates for the dental assistant (5 percent) and insurance coordinator (25 percent).

However, it is not just the allocation of costs that undervalues hygiene's contribution to profitability. Hygienists typically spend five minutes of each recall appointment doing a dental exam, which the dentist reviews before speaking to the patient. If the hygienist sees 10 to 12 patients a day, these exams could account for 20 percent of the hygienist's time. If the dentist takes credit for this production, then 20 percent of the hygienist's salary and 20 percent of the rent and support staff's salaries allocated to hygiene should be charged to the dentist.

Reviewing our analysis, we started out with "the practice is either losing money or making only a slight profit" on hygiene. If hygienists make a significant contribution to the profitability of a dental practice (Table 2 and Table 3), why do statements such as "hygiene is just a convenience for patients — it really does not make any money" persist?

There is a range of explanations. At one end is a lack of understanding financial relationships, and on the other end is the myth that hygiene is not profitable, in order to discourage proponents who foster the idea of hygienists becoming independent contractors.

A question that dentists are unwilling to address is if hygiene typically loses money or only breaks even, why are hygienists not allowed to be independent contractors? The answer is that most practices would be considerably less profitable without hygiene. Does this mean that dental hygienists could earn their salary plus $25,296 (Table 3) in profit? Perhaps, but the independent hygienist would also have to rent office space, hire staff, and build a patient base, which involves a measure of risk. We believe that dentistry and dental hygiene complement each other and that this union should equitably reward both groups of professionals.

Annmarie Bernardi, RDH, BS, has been a practicing hygienist for more than 20 years and is a graduate of the University of Vermont's School of Dental Hygiene and the State University of New York. She has done extensive work in public health and integrative medicine and has been a member of the Mission of Hope's Medical Team for two trips to Nicaragua to provide medical help to a remote village, an orphanage, and victims of Hurricane Mitch. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Richard Bernardi, PhD, CPA, is a professor at Roger Williams University in Bristol, R.I., teaching financial and managerial accounting, finance, and business ethics. He has authored more than 50 articles in accounting, ethics, fraud detection, and gender issues. In 1997, he received the State University of New York Chancellor's Award for Teaching Excellence.